Energy and Curiosity Drive Professor

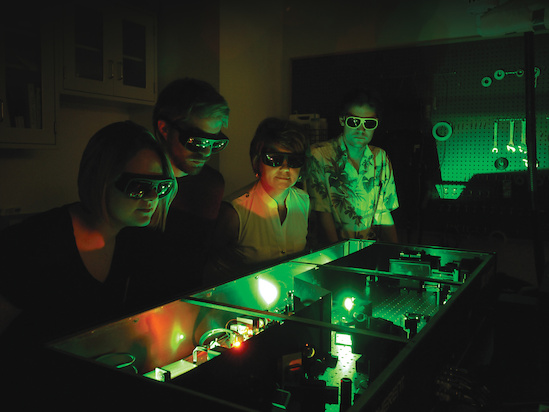

(L-R) Chemistry graduate students Hannah Ogden and Paul Diss, Professor Amy Mullin and intern Augustus Cooke-Nesme (University College London) inspecting their laser system that generates highly excited molecules. Photo: Faye Levine / University of Maryland.

When she first started graduate school, people told University of Maryland Chemistry and Biochemistry Professor Amy Mullin, “You’re never going to finish” and “You’re never going to get an academic job.”

They were wrong. In 1991, Mullin earned her Ph.D. in physical chemistry from the University of Colorado, Boulder, and went on to become an assistant and then associate professor of chemistry at Boston University, where she served until coming to UMD in 2005.

“When I gave a research talk, I wanted it to be well prepared and presented well so that the audience would be as interested as I was,” says Mullin, who was the youngest faculty member in her department at Boston University and the only woman. “When I taught a class, I wanted students to feel that it was worth their while to be there.”

Mullin’s exceptional teaching has earned her two top awards. She received a Camille Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar Award in 1999 and the Creative Educator Award from UMD’s College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences in 2011.

Since joining the faculty at UMD, Mullin has developed new graduate courses in kinetics and dynamics and created new methods for teaching physical chemistry courses.

“I develop my own lesson plans for fun and active learning. My goal is to have my students be motivated and active learners,” explains Mullin. “I try to make lectures interesting by incorporating demos, videos and discussions.”

Mullin says she can spot a spark of success in certain students that goes beyond getting top grades in chemistry classes.

“The kids that I see going far,” she says, “are those who are genuinely curious.”

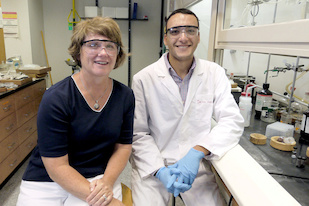

One such student was Matthew Smarte, B.S. ’12, chemistry, who is currently a graduate student studying atmospheric chemistry at the California Institute of Technology. Mullin mentored Smarte through the Beckman Scholars Program that she directs. Since 2007, the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation has funded 18 scholars at UMD, providing financial support for undergraduates to conduct research with faculty mentors for at least 15 months.

“The Beckman Scholars Program provided me with invaluable professional development and an almost seamless transition to graduate school,” says Smarte. “I thoroughly enjoyed working with Professor Mullin and learning from her tenacious approach to science. When a new experiment posed challenges, she remained confident that a solution and success were right around the corner.”

“The Beckman Scholars Program provided me with invaluable professional development and an almost seamless transition to graduate school,” says Smarte. “I thoroughly enjoyed working with Professor Mullin and learning from her tenacious approach to science. When a new experiment posed challenges, she remained confident that a solution and success were right around the corner.”

Two things tie Mullin’s research pursuits together: molecules and energy.

“Energy is the thing that drives all change,” she says. “If we were in equilibrium, there would be no life.”

A fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the American Physical Society, Mullin currently receives funding from the U.S. Department of Energy, the National Science Foundation and NASA.

For one project, Mullin studies the unusual behavior of gas-phase molecules—including carbon monoxide and nitrous oxide—which act like tiny gyroscopes when she applies strong optical fields to them. The optical fields allow Mullin to add controlled amounts of energy to the molecules and get them spinning in high rotational states to observe how they respond.

Mullin also investigates whether ultraviolet-induced bond-breaking of sulfur dioxide could explain the ratio of isotopes on the early Earth, which she hopes will help scientists identify the signals of exoplanets that are evolving, or have evolved, to be Earth-like.

In another project, which could lead to more efficient car engines, Mullin examines how collisions induce energy flow between molecules that contain large amounts of vibration.

She also studies how light can control a technique called nanolithography to pack memory features closer together and create devices with more digital memory.

Mullin has built a thriving research program at Maryland—thanks in part to her own energy and curiosity—and has been able to push the prejudice and resistance she experienced early in her career into her rearview mirror.

Written by Rachel Crowell

This article was published in the Fall 2016 issue of Odyssey magazine. To read other stories from that issue, please visit go.umd.edu/odyssey.