Chemical Traces of 2023 Canadian Wildfires Detected in Maryland Months After Smoke Subsided

A new University of Maryland study of campus air samples revealed that chemical compounds from Canada’s historic 2023 fires lingered in the air, forming an ‘atmospheric soup.’

In 2023, Canada’s worst wildfire season on record produced so much smoke that it spilled across national borders into the United States. At times, a thick haze enveloped much of the U.S. East Coast and triggered “Code Purple” and “Code Maroon” alerts—the most hazardous air quality warning categories—in the Washington, D.C. region.

More than 1,000 miles from where the smoke originated, a group of University of Maryland researchers seized the rare opportunity to directly analyze wildfire plumes—a pollutant that plagues the U.S. West Coast far more frequently than the East Coast. Their findings, published in the journal Environmental Science: Atmospheres, revealed that chemical compounds from Canada’s wildfires remained in the atmosphere in College Park, Md., months after the smoke subsided, raising concerns about the potential health and environmental effects.

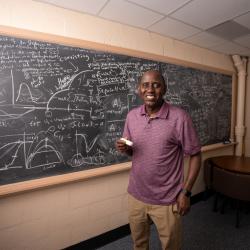

“Even when the Air Quality Index was good—long after the fires started to dwindle—we still found similar compounds that we saw during the Canadian wildfire event,” said study senior author Akua Asa-Awuku, a professor in UMD’s Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering.

In the future, their findings could help improve predictive models used to study wildfires and their effects. Most chemical composition studies of long-range smoke plumes rely on federal agency satellites and planes that fly through wildfires to collect samples. On-the-ground testing is rarer, making UMD’s study unique.

“To our knowledge, no study data provides a molecular-level composition of the 2023 Canadian wildfire plumes,” said the study’s lead author, Esther Olonimoyo, a UMD chemistry Ph.D. student. “This is a pretty complex area of study where more work still needs to be done in understanding the chemical composition of wildfire plumes.”

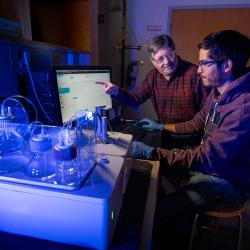

When Canadian wildfire smoke first arrived on campus, Asa-Awuku, Olonimoyo and their co-authors collaborated with Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Science researchers to collect air samples from the rooftop of the university’s Atlantic Building in June 2023, August 2023 and February 2024.

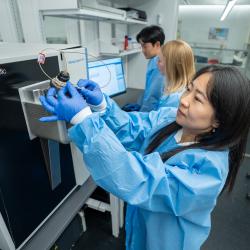

The researchers took those samples back to Asa-Awuku’s Environmental Aerosol Research Laboratory for chemical analysis using a high-pressure liquid chromatography method developed by Olonimoyo and study co-author Candice Duncan, an assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Science and Technology.

Their method was designed to quickly and accurately analyze organic acids, which are carbon-rich compounds—including ones found in wildfire smoke—that can negatively affect the climate and human health when concentrated in the atmosphere. While smoke plumes peaked on campus in June 2023 and visibly dissipated by August, the researchers discovered that air samples collected in August still contained the chemical traces of wildfire smoke.

Those samples were collected on a day when the Air Quality Index (AQI) was good, suggesting that compounds from wildfire plumes may linger in the atmosphere longer than expected.

“We see the persistence of compounds in the atmosphere beyond what the air quality indices tell us,” Olonimoyo said. “That raises public health concerns that people might still be exposed to certain compounds even after air quality indices have significantly improved.”

The researchers identified different classes of carbonaceous chemicals in the air, including some that could be toxic to humans in high concentrations. Asa-Awuku noted that the AQI measures five major pollutants and does not account for a wider range of chemical species—including atoms, molecules, ions and radicals—in the atmosphere.

“The AQI provides a general assessment of overall air quality for the region,” Asa-Awuku said. “The AQI was high when there was a lot of particulate matter from the wildfire emissions, but the AQI tells us little about the chemical composition of particulates.”

It wasn’t until February 2024—eight months after the wildfires—that researchers saw a significant decrease in wildfire-associated compounds. Asa-Awuku suggested that the compounds they observed may have interacted with gases in the atmosphere, triggering chemical reactions that made them stick around longer.

“A lot of the compounds that we analyzed don’t dissipate like a primary emission, which is emitted directly into the atmosphere,” Asa-Awuku explained. “They are persistent over time and space, which suggests that they are part of an atmospheric soup that’s generating more and more of these organic compounds with time.”

Studying these compounds—and their ability to dissolve in water—can help researchers understand their longer-term impact on the environment. Some chemical compounds from wildfire plumes react with water vapor and wind up in clouds, so when it rains, they can infiltrate the soil and alter the Earth’s natural biogeochemical cycle.

Moving forward, Olonimoyo plans to analyze these compounds in greater detail and identify the ones with unique signatures. Ultimately, she hopes their findings will help the scientific community make better predictions about wildfires and their impact on people and the environment.

“Knowing the molecular composition of these plumes is very important in model predictions,” Olonimoyo said. “The scientific community can make better predictions when they have more accurate knowledge, and it also helps us assess the likely implications if certain compounds are present in the atmosphere.”

###

In addition to Olonimoyo, Asa-Awuku and Duncan, UMD co-authors included Yue Li, director of the Mass Spectrometry Facility in UMD’s Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, and Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering Ph.D. students Martin Changman Ahn and Dewansh Rastogi (Ph.D. ’23).

The paper, “Chemical signatures of water-soluble organic carbon (WSOC) fraction of long-range transported wildfire PM2.5 from Canada to the United States Mid-Atlantic region,” was published in Environmental Science: Atmospheres on November 25, 2025.

This research was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation. This article does not necessarily reflect the views of this organization.