Dung Beetles and Butterflies Highlight the Consequences of Amazon Rainforest Fires

In late August 2019, uncontrollable fires spreading on the edges of the Brazilian Amazon rainforest sparked international alarm and an outcry for urgent action.

Although Brazilian agriculture practices typically involve setting massive plots of the rainforest on fire to help clear land for crops and pasture, the increasing frequency and spread of these fires every year is a cause for serious concern.

Although Brazilian agriculture practices typically involve setting massive plots of the rainforest on fire to help clear land for crops and pasture, the increasing frequency and spread of these fires every year is a cause for serious concern.

To understand the consequences of the fires on the Amazon’s local biodiversity, Rafael Andrade, a native Brazilian and visiting assistant research fellow in the University of Maryland’s Department of Entomology, looked to the dung beetle and butterfly populations for answers, seeing them as perfect indicator species.

He discovered that in regions where agricultural fires occur there is local extinction of specialized species, and the once-vibrant forests become impoverished, despite appearances.

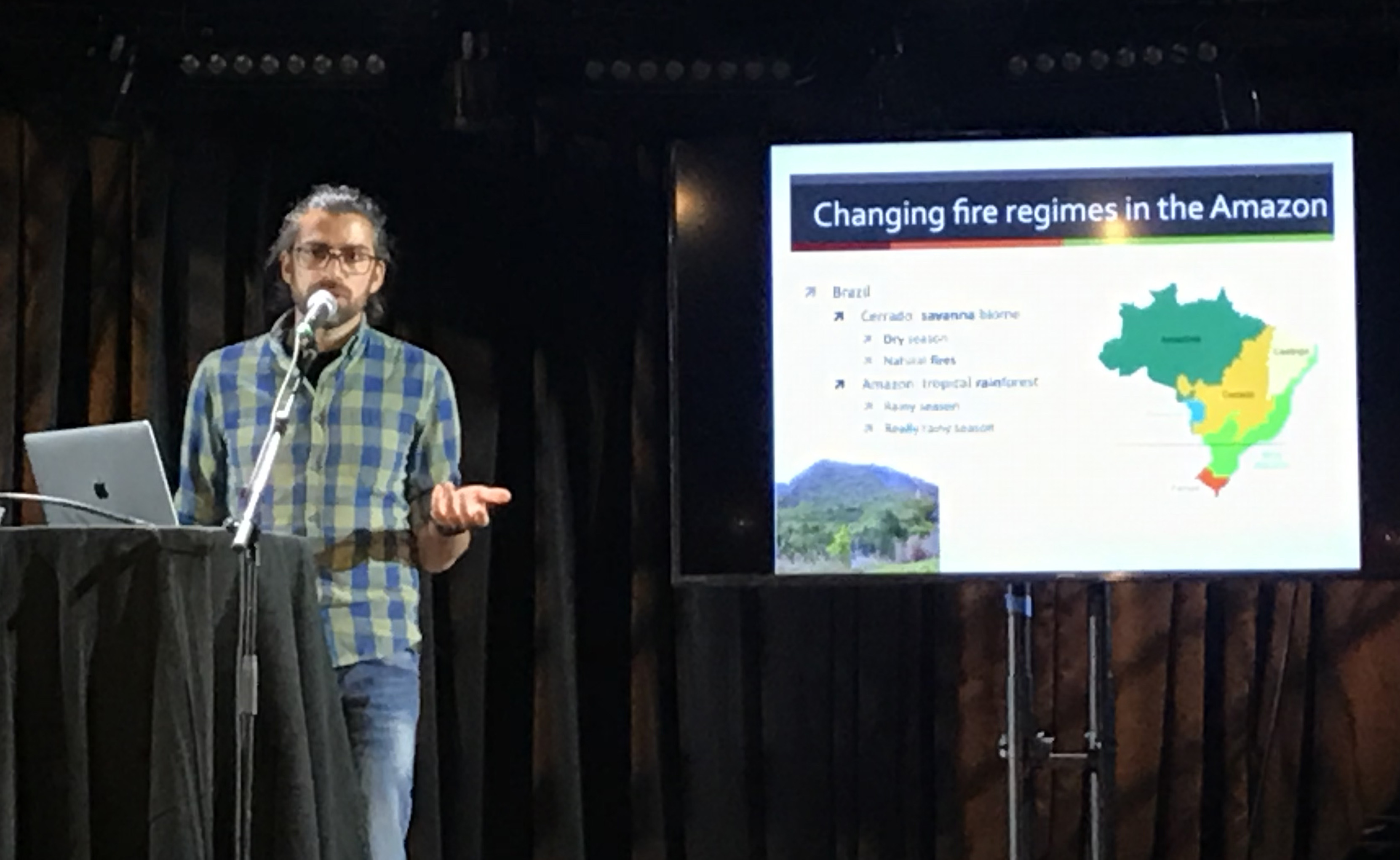

On Dec. 4, 2019, at the Science on Tap lecture series hosted each month at MilkBoy ArtHouse by the University of Maryland’s College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences, Andrade highlighted his research from when he was a Ph.D. student at South Dakota State University. His work showed insects to be useful indicator species for biodiversity, especially in the Amazon forests. He also shed some light on Brazil’s tumultuous politics and current environmental policies that experts point to as the main cause for the severity of this year’s fires.

Andrade began his lecture by first explaining that wildfires do not naturally occur in the Amazon.

“The quintessential Amazonian forest looks like this: you have a rainy season and a really rainy season,” Andrade said. “One of the times I was working there, I started to complain to my field guide that I was losing too many days because of the rain. I couldn't go to do my samplings, and I would have to come back in the dry season. To which he replied, ‘We are in the dry season.’”

Even in the rainforest’s dry season, between June and December, natural wildfires do not typically occur.

“All fires are associated with human occupation and land use, so it needs the human presence as the ignition source,” Andrade said.

Large- and small-scale farmers alike use the agricultural technique called slash-and-burn, in which landowners log a certain area of the foresta and then burn the biomass that remains, like weeds and other plants, so they can use the land for pasture or crops.

“[Smallholders] depend on this technique of slash-and-burn for their livelihoods. They can’t [farm] without this technique,” Andrade explained. “[The slash-and-burn fires are] not that impressive. It’s a fire about the height of your feet and you can just walk over it.”

If the technique is so common in practice and doesn’t cause such wildfires, why are there increasing numbers of severe fires in the Amazon, as reported by Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research?

Ten-year-old Phoebe Yonkos, who sat in the crowd listening to Andrade’s lecture, was also confused by this. She came to the event with her father Lance Yonkos, an associate professor in the Department of Environmental Science and Technology.

She asked Andrade, “Why [are the fires] happening so much if it’s so wet?”

Andrade explained that climate change, accelerated by deforestation and fires in the Amazon, results in parts of the forest generating the right conditions for fire to spread easier and become out of control.

“In regions where you have a dry season or have a dry forest, climate change makes these conditions even more dry so it doesn't take much for fire to spread,” Andrade said.

Fires also emit more carbon in the short term than logging forests, said Andrade, citing a 2017 article he co-authored in the journal Carbon Balance and Management about the Amazon’s carbon emissions. These emissions worsen climate change, which then aggravates the fires, causing this “feedback.”

“So when you have this increase in fire frequency in a biome that evolved without fire, you have organisms that can’t stand fire,” Andrade said. “My studies were mostly asking the question of what happens to the local biodiversity with this increasing frequency of fires in the Amazon.”

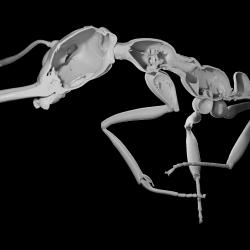

For one of his studies, Andrade chose to use the dung beetle as an indicator of biodiversity because they are easy to sample, there are many of them, and they play a major ecological role in the forest cycle.

Dung beetles do exactly what they are infamous for doing: feed off the feces of vertebrates and lay their eggs in the pile of dung. Some species, known as tunnelers, bury the excrement where they find it, and other species roll all the waste into a round ball and then tunnel into the ground, taking the balls of dung with them.

In some dung beetle species, males roll the feces into a ball and “offer it to the female as a romantic gift,” Andrade said.

In this removal of dung, the beetles provide very important ecological functions for the rainforest’s ecosystem, such as:

-

Nutrient cycling: Dung beetles are the first to break down the feces of vertebrate species, which is further broken down by microorganisms.

- Parasite control: By removing the dung (feces that would otherwise be populated by flies and parasites) dung beetles help control the population of parasites in the forest.

- Soil aeration: When the dung beetles dig their tunnels they help the soil aerate, alleviating soil compaction and incorporating nutrients into the soil.

- Seed dispersal: As they roll their balls of dung along the rainforest floor, the dung beetles inadvertently transport seeds that are in the dung ball to other locations.

These activities are beneficial and an integral part of this network, in which the vegetation is dependent on these dung beetles and the beetles directly affect the very vertebrates that produce the feces.

“Any change in a plant community or the vertebrate community will reflect on changes in the dung beetle biodiversity. That’s what makes them great indicators,” Andrade said.

Daniel Gruner, an associate professor in the Department of Entomology and Andrade’s mentor, came to learn more about the work Andrade did before he joined UMD.

“I think that a lot of people ignore these little things that run the world,” Gruner said. “You know, the insects are really making our lives possible. If we didn't have dung beetles and small insects to remove our waste, and not just to remove it, but to reprocess it into functioning ecosystems systems, the world will not function to the same extent.”

Andrade’s research included sampling at four different locations of the Amazon, including one in the southern area where there is more seasonality and more slash-and-burn. Andrade first compared the biodiversity and body size distribution of dung beetles in an unburned, control forest with a forest that had burned 11 years prior to the sampling.

At each of these locations, Andrade found plenty of dung beetles; however, there was something missing in the burned forest sampling collection--a very large species of dung beetles, the Coprophanaeus lancifer.

“If you look at the medium-sized species, you would see much less density of the species in the burned forest and dominance of the smaller ones in the burned forest,” Andrade said.

Andrade and his team also identified which species are typical in the unburned and burned forests and what habitat changes drove this difference.

“We basically saw that these species were responding to how hard the soil was in the forest. Meaning that species associated with the control forest, the harder the soil was the less you would find them,” Andrade said.

The hardened soil makes it almost impossible for the larger tunneler species to dig into the soil surface.

“Even years after this fire event, we would find these impoverished dung beetle communities, showing the lower biomass, and these bigger species responding to soil hardness,” Andrade said.

Andrade’s study concluded that this was an indication of the local extinction of these specialized species. Even when the same number of beetles exists but the population is comprised of smaller species, scientists see a significant decline in these important processes happening in the forest, which leads to an impoverished forest.

In a similar study, Andrade looked at differences in butterfly populations in burned and control forests and found that fire caused a shift in the species composition.

However, in this research, Andrade and his team joined an ongoing project that burned a plot of rainforest every three years, a frequency that simulates how often the El Niño event happens, which is a climatic event that makes the dry season much drier and increases fire occurrence. Another plot was burned every year, trying to simulate the frequency in which agricultural practices would burn the forest.

Andrade mentioned that one may not notice the effects of the fire initially, but over time the forests would become less and less resistant to fires. And it’s just going to get worse, he said.

Not only is it going to get worse because the forests are less resistant to fires each year, but the current environmental policies allow for complete disregard of protecting the Amazon, Andrade said. The fires this year were directly linked to high rates of deforestation. Deforestation in July 2019 was almost four times the average of the same period in 2016 to 2018, he said.

“This administration is actively in the process of dismantling the infrastructure in Brazil that we have for conservation,” Andrade said.

For instance, the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources would normally have the support of the local police forces and the National Guard, however the institute is seeing much less of that now, Andrade said. There are also changes in the administration, where there were once conservationists and biologists in authoritative positions, police officers and military officers have taken their places.

With any negative report about the environment, the science is called “fake news” and the scientists are its perpetrators. Scientists in Brazil are facing persecution, said Andrade.

“This is a government that defunds and mistrusts science, and there is no greater damage to the environment than this,” Andrade said.

Despite this belittling attitude toward science in the Brazilian political realm, Andrade and other scientists still carry on with hope for the future.

“The current political regime we're seeing is pretty devastating to the morale of science. But this too will pass,” Gruner said. “I think there will be a reaction to this. I think that people are a lot stronger than an individual leader or an individual government and that the truth will prevail.”

Media Relations Contact: Abby Robinson, 301-405-5845, abbyr@umd.edu

Writer: Nicolle Schorchit

University of Maryland

College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences

2300 Symons Hall

College Park, MD 20742

www.cmns.umd.edu

@UMDscience

About the College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences

The College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences at the University of Maryland educates more than 9,000 future scientific leaders in its undergraduate and graduate programs each year. The college’s 10 departments and more than a dozen interdisciplinary research centers foster scientific discovery with annual sponsored research funding exceeding $175 million.