Small Wonders

Maryland State Entomologist Max Ferlauto (Ph.D. ’24, entomology) is working to protect some of the state’s smallest—and rarest—inhabitants.

Every day, in diverse habitats all over Maryland, Max Ferlauto (Ph.D. ’24, entomology) works to protect some of the state’s smallest natural wonders. Many are known for their beauty, some for their creepiness and others are seldom seen at all. But to Ferlauto, who has served as state entomologist in the Maryland Natural Heritage Service, within the MD Department of Natural Resources (DNR) since 2023, Maryland’s rarest insects—whether they creep, crawl, burrow, or fly—are resources worth protecting.

“Insects are important because they’re the foundation to the food chains of most wildlife, and they perform fundamental roles vital to our ecosystem, like decomposition and pollination,” he explained. “Rare insects, though, often are underprioritized in conservation compared to larger, more charismatic groups.”

Ferlauto took on the role of state entomologist before he even finished his Ph.D. at the University of Maryland, and since then, he’s been active in the state’s broader wildlife conservation effort, surveying the state’s insects—especially the rarest ones—and making sure their futures are secure.

“There are some states where insects are not even considered wildlife, and that can make or break insect conservation,” Ferlauto noted. “Luckily, Maryland does, and we have a very expansive list of rare species in Maryland, so we know where to prioritize conservation.”

Checking on the ants, imagining the possibilities

Ferlauto’s passion for conservation, and insects in particular, started in the Arlington, Virginia, neighborhood where he grew up.

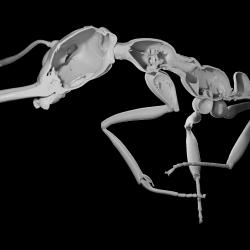

“Insects were all around, so they were easy to get up close to. When I was 6 or 7, I had an ant hill that I was monitoring, and I would go out there every day after school to check on the ants,” he recalled. “I got this book about creating a habitat, a zoo in your own backyard, and I remember thinking that I wanted to see if my backyard could be like a zoo, attracting birds and amphibians and insects.”

In high school, Ferlauto’s passion for wildlife and the outdoors grew. Fascinated by Maryland’s vast array of wild plants and mosses, he joined local environmental groups for nature walks and plant identification projects. Later, as an undergraduate at Juniata College in Pennsylvania, he leaned further into botany, majoring in plant ecology. And as he studied native and non-native trees, the species they attracted, and the dynamics of ecosystems, Ferlauto discovered an unexpected passion for research, particularly in entomology.

“For my undergraduate research, I had to sit and identify thousands of insects, so I was spending a lot of time with them. That started shifting my interest,” he explained. “I was like, this is super cool. I want to do research.”

After receiving his bachelor’s degree, Ferlauto joined the Department of Entomology at UMD for graduate school. Fascinated by what he read about Entomology Associate Professor Karin Burghardt’s research exploring how native plants support insect communities, he knew he wanted to be part of it.

“I knew of the work that she had done, and I saw that she was opening a lab and recruiting for grad students, and that was huge for me,” Ferlauto explained. “Karen is amazing. She gave me the freedom to do what I wanted to do, but she was also hands-on enough in the beginning to give me the confidence to take the research where I did.”

With Burghardt’s support, Ferlauto’s research ramped up quickly. He wanted to explore how the familiar fall ritual of raking and removing fallen leaves affected local insect communities, and specifically whether leaving the leaves on the ground would be a more sustainable option.

“Ultimately, the question was what happens when you remove leaves in the fall, and then we added some other things like what happens when you mulch leaves or shred them or create a leaf pile,” Ferlauto said. “I wanted to know if removing this leaf litter would reduce the number of emerging insects the next spring, and the answer was yes it did.”

‘That zoo in your backyard’

From his extensive work in a research forest at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center in Edgewater, Md., to a two-year study with homeowners in the College Park area, Ferlauto’s work confirmed his theory that leaving leaves on the ground instead of raking or blowing them away improves the soil and supports local ecosystems by preserving insect communities. For Ferlauto, who published two first-author papers on the work and has shared his findings with countless master gardeners, community groups and property owners, bringing that conservation message to people who can apply it in their own backyards is especially important.

“At UMD, my lab and the labs that we worked with were really focused on urban ecology, and that’s been a huge influence on me, helping me understand ecology at a landscape level,” he explained. “I wanted my research to explore a more insect-friendly approach to landscaping. How can we create that zoo in your backyard? How can we make our backyards more sustainable?”

In 2023, as Ferlauto continued working on his dissertation, a surprising job posting showed up. The position: Maryland State Entomologist. Ferlauto applied and landed the job.

A once-in-a-lifetime opportunity

"I had to go for it because this was a position that doesn’t come around often at all. It was a Natural Heritage position, and those tend to be filled for a very long time,” Ferlauto recalled. “I was a little worried because it meant I’d have a full-time job and my dissertation had not been fully written. But at the end of the day, I was able to finish my Ph.D., write a really good dissertation and take this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”

Since then, Ferlauto has spent countless hours crisscrossing Maryland’s diverse environments and ecosystems to seek out and survey the state’s local and regional insect populations.

“We just have such a diverse set of ecosystems and natural communities here, and we have some species here that are known only to be in Maryland, and that’s one of the joys of my job,” he explained. “One week I’ll be on a mountain in western Maryland protecting tiger beetles, and then the next week I’ll be protecting butterflies that live on a sand dune on the Eastern Shore, or I’m on a boat monitoring beetles on a cliff in the Chesapeake [Bay]. Some of our ecosystems hold globally rare species. And we need to protect them.”

Ferlauto also contributes to the state’s long-range wildlife conservation goals, drawing on his field work and research experiences at UMD to advance Maryland DNR’s broader vision for a more sustainable future.

“Right now, we’re working on a State Wildlife Action Plan, which comes every 10 years, so I’ve gotten to be involved in the insect component of that, and I’ve learned so much,” he said. “My community ecology experience at Maryland was invaluable, and now that we’re creating this master plan, I think my UMD experience will make a huge difference. My ultimate goal is to use the work I’ve done with homeowners and landowners to bridge the gap between the so-called wilderness of Maryland and the working land—the places where people live.”

Ferlauto believes the more we know about Maryland’s rarest insects and their role in the delicate balance of the state’s diverse ecosystems, the more we can do to protect them.

“At this point, I’ve been to pretty much all of the rare insect populations that we have in the state, and I have a plan for all of them,” he explained. “As long as we can fund that plan and create and manage the habitats properly, I have high hopes for insect conservation in Maryland. It’s very exciting.”