Growing Organically

How science and a family tradition of farming helped Andrew Smith (M.S. ’02, entomology) see organics in agriculture’s future.

When Andrew Smith (M.S. '02, entomology) travels across the countryside in his home state of Pennsylvania, he doesn’t just see fields and farms and homes—as a farmer and a scientist, he sees much more.

“When I'm driving to and from work, I'm always thinking about the fields and what could be done on those fields,” he said. “And I have this insatiable curiosity that gets to be fulfilled through the work that I'm doing.”

In addition to being the owner and operator of a family farm near Philadelphia, Smith is also the chief scientific officer at Rodale Institute, an agricultural and research nonprofit that has been a global leader in regenerative organic agriculture since 1947. Thanks to his experience as a farmer and a scientist, Smith believes the best agricultural practices for growing crops and raising animals are the ones that improve the quality of life for both farmers and consumers.

“Instead of just looking at how much we can grow or increase crop yields we should be looking at the impact on people of how we're growing crops,” Smith explained. “We need to continually look to nature as we create our farming systems.”

Over the past 20-plus years, Smith conducted integrated pest management studies at the University of Maryland, helped struggling Guatemalan farmers in his work with the Peace Corps, and took on a variety of plant and animal challenges on his own Pennsylvania farm. Since 2018, in his work at Rodale, Smith has overseen scientific research aimed at helping farmers fight weeds, pests and disease without chemicals, supporting Rodale’s mission to promote agriculture that’s healthier for people, animals and the environment.

“The farmers that embrace organic or a different, more environmental approach, a more knowledge-intensive approach, are going to be successful,” he noted. “They're going to be here 20 years from now.”

A family tradition

For Smith, a family farming tradition—and the hard work that went with it—was part of growing up.

“We had sheep, we had cows, we always had horses, and then, as my dad retired, he bred horses,” Smith recalled. “So, I was always mowing grass and weed-whacking fence lines on the property. There was always work to do.”

Years later, as an undergraduate at Cornell University, Smith discovered agronomy and sustainable agriculture, gaining new insight into the farming traditions of his childhood. Soon after he graduated, he joined the Peace Corps, working in Guatemala.

“Since I had a degree in agronomy, they placed me working with small-scale farmers who were trying to make a living on one to two acres. Mostly, they were spraying illegal pesticides and their shipments to the U.S. were getting denied—so they didn’t get paid,” Smith recalled. “And seeing these farmers spraying pesticides, often while they're in the field with their wives and kids, my thinking was, how can we do something to reduce this chemical use?”

With a growing interest in integrated agricultural pest management, Smith connected with the Department of Entomology at UMD and an innovative professor named Dale Bottrell.

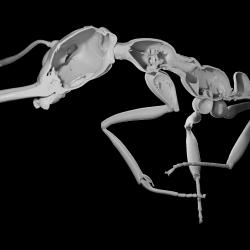

“Dr. Bottrell, he was really one of the first to study integrated pest management—he literally wrote the book on integrated pest management. I worked with him for my master's, looking at how we can increase biodiversity and natural enemies to reduce pest populations,” Smith explained. “My curiosity about questions like that was what got me into science, and the University of Maryland helped me understand science, why we do it, and how we do it.”

From Beltsville to Rodale

For Smith, field studies on a UMD research field in Beltsville, Maryland, sparked a broader interest in a more natural approach to farming.

“For research purposes, we wanted to measure insects, and we didn't want to kill them with insecticides,” Smith recalled. “In this case, we were trying to see if growing buckwheat, which we knew attracted the natural enemies of European corn borers, could control those insects. And that put me on the trajectory of organic farming,”

After earning his master’s in 2002, Smith and his wife started their own family farm, growing organic fruits and vegetables until he began his doctorate in environmental science at Drexel University. Just days after Smith completed his Ph.D. in 2015, he got a job offer from Rodale, an institute dedicated to promoting the natural approach to agriculture that already had Smith’s attention.

“Literally, I defended my thesis on a Thursday,” he recalled, “and I got called by Rodale Institute Friday.”

Smith was hired to launch Rodale’s Vegetable Systems Trial, a long-term, side-by-side study comparing organic vegetable farming with conventional growing methods using chemicals.

“The goal was to try to link soil health to human health and understand how, if we improve the health of the soil, does that make the crop more nutrient-dense, or improve nutritional quality, and therefore, make people healthier,” Smith explained. “And the idea was, let's put more science behind this concept that improved soil health could lead to improved human health.”

Smith soon became the institute’s interim research director, then chief scientific officer, supporting Rodale’s ongoing field studies, from soil surveys to weed management strategies. As a farmer and a scientist, Smith believes—and Rodale’s research has demonstrated—that organic farming without chemicals can be as productive, more profitable and better for long-term human and environmental health than conventional farming methods using chemicals.

Close to home

“If we take this organic approach, it improves soil, it improves water quality, improves air quality, so let's create new tools and new technology and new innovations for farming that aren’t relying on chemicals,” Smith said. “I believe in organic farming, and so, both at Rodale and personally, I believe increasing the number of organic farms improves everything else in life.”

Smith’s commitment to organic agriculture also hits close to home. Though the family farm he runs with his wife and kids has evolved over the years, everything—from raising the animals to growing the blooms—is still done naturally.

“Our farm and sheep are now certified organic, we now have a small wool mill, and my wife also grows peonies and tulips. She calls it a farm for spring,” Smith said. “We're living in harmony with nature.”

With support from the scientific research at Rodale and the institute’s ongoing efforts to promote regenerative organic agriculture, Smith hopes to increase the number of organic farms worldwide and give farmers—and the communities who depend on them—a brighter future.

“To me, it's meaningful because I'm thinking about the next generation, my kids and my grandkids, we should be thinking generations ahead, right?” Smith reflected. “And if we can make progress, even make baby steps toward a solution, that matters.”