Portraits of Humanitarians

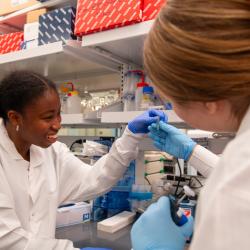

Humanitarian work is often viewed as reactionary—offered in times of crisis—or as a mission requiring one to travel the globe. But, for six University of Maryland alumni, humanitarian service begins at home, ensuring quality health care for people in their local communities day after day. Putting people first starts with one mammogram, one counseling session or one pulled tooth. And, perhaps even more importantly, it requires a health care worker willing to listen, look past stereotypes and find creative solutions.

During their years of practice, these six physicians and dentists have kept the Hippocratic oath or the American Dental Association’s Code close to their hearts by building lifelines for those in need. All have given their own time to ensure that those in their local communities who can’t afford the benefits of modern health care still receive the help they need.

Anne Nucci-Sack

Privacy and Protection for At-risk Teens

At the Mount Sinai Adolescent Health Center in New York City, teens and young adults know they will get outstanding care, free medicine and confidential support all in one place.

At the Mount Sinai Adolescent Health Center in New York City, teens and young adults know they will get outstanding care, free medicine and confidential support all in one place.

If that knowledge isn’t enough to get them through the door, they can send questions via text message or sign up for a Health Squad app that reminds them to take medications.

The center’s medical director and chief medical officer, Dr. Anne Nucci-Sack, B.S. ’77, microbiology, makes it her job to get patients the treatment they need regardless of their ability to pay. She does so with an approach that takes into account their collective physical, mental and sexual health needs.

“We treat patients. We don’t treat problems or diseases,” Nucci-Sack says. “There is this burgeoning sexual and reproductive health background and a lot of depression and anxiety during adolescence—both pieces that often get missed.”

Listening to the patients—many who come from low-income areas or lack strong family support—builds a bond that can translate to better care.

Though she tried private practice, Nucci-Sack says she had an epiphany long ago that helping children in communities with less access to quality health care is her calling.

She spent 18 years in the Bronx working with mentors she met during her pediatric residency. After completing a fellowship that allowed her to better understand the challenges teens and young adults face, she became chief of adolescent medicine for the Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center and ran its school-based Taft Teen Health Center for 15 years.

In 2002, Nucci-Sack moved full-time to the Mount Sinai Adolescent Health Center. It houses a block’s worth of services, targeting patients from East and Central Harlem, areas with some of New York’s highest teen pregnancy rates. Patients come from all over New York City, and teens and young adults who are visiting from other states also accompany cousins or friends to get help they can’t find elsewhere.

The center’s reputation—particularly the fact that it only bills for services if it can do so without alerting parents to a young person’s treatment—has grown with the internet. But the 10,000 patients aged 10 to 24 served each year come for the same basic reasons they always have: a sense of caring that’s intentionally non-paternalistic.

Nucci-Sack spends about 50 percent of her time treating patients, but also works toward the larger goals of strengthening and expanding programming, and educating pediatric residents in adolescent health. The center depends on donors (including staff members who run the New York Marathon) to raise its $12 million annual budget.

Stories like those of former patient Jose Pacheco make soliciting support a bit easier. Being bullied and weighing nearly 400 pounds, Jose turned to center staff for help. They diagnosed a heart condition, taught him about nutrition and connected him with fitness mentors to put him on a path to wellness.

“Poverty is really a very potent entity in many of these kids’ lives,” Nucci-Sack says. “Many of our patients have disorganized lives. They’ve witnessed violence. They report physical, emotional and sexual abuse, as well as trauma. They need somebody to sit down and talk to them … someone who they know is advocating for them.”

William Ward

Flying to the Rescue Out West

In the 1960s and 1970s, Dr. William Ward, B.S. ’54, chemistry/pre-med, logged more than 12,000 hours in a Beechcraft Bonanza, his vehicle of choice for reaching remote hospitals too small to boast their own radiologist.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Dr. William Ward, B.S. ’54, chemistry/pre-med, logged more than 12,000 hours in a Beechcraft Bonanza, his vehicle of choice for reaching remote hospitals too small to boast their own radiologist.

After medical school—and two semesters spent in the radiology department at the National Institutes of Health—Ward knew he wanted to practice in the rugged wilds of Colorado and Wyoming.

When he arrived in Laramie, Wyoming—a town of just 20,000 residents—in 1962, Ward was only the third radiologist. For some residents of small towns at that time, getting the right treatment required X-rays be mailed out and interpreted by a professional hundreds of miles away. Other patients made the arduous trip in person or risked a bad read by an undertrained technician or local medical examiner.

Ward wanted to bring emerging diagnostic technologies to more patients, so he began commuting by air. He spent his early days diagnosing wounds from ranching accidents, many involving horses or tractors. He also treated patients on Indian reservations and other locations with medically underserved communities. As more radiologists began to arrive in the West and new safety standards reduced the rate of some traumatic injuries, Ward added ultrasound to his arsenal and expanded to helping breast cancer patients.

“I was able to perform medical exams they hadn’t been doing in these places,” Ward says. “I was lucky in my practice, especially treating cancer, because the medical advancements and the equipment became so refined.”

He went back to school to stay informed about new procedures and worked to convince women that they would benefit from previously unknown tests—such as mammography and ultrasounds—and sometimes-clunky machines. Within years, he had technology that could pick up masses months earlier when they were centimeters smaller.

Always eager to stay up-to-date, he spent a summer at Southern Illinois University and then went to St. Luke’s Hospital in Fargo to learn about neurological MRIs. He also chaired the Wyoming Board of Medicine before retiring in 1995.

As much as Ward loves the West, he gave up a small part of it to ensure a better future for its residents. He and Carole, his wife of 40 years, sold their ranch land to fund scholarships for medical students who agree to practice in Wyoming or parts of Colorado.

Sherita Hill Golden

On a Mission to Control Diabetes

Inside the Johns Hopkins Outpatient Diabetes Center on Baltimore’s Caroline Street, Dr. Sherita Hill Golden, B.S. ’90, biological sciences, works hard to prevent the kind of life-changing damage suffered by one of her earliest patients.

Inside the Johns Hopkins Outpatient Diabetes Center on Baltimore’s Caroline Street, Dr. Sherita Hill Golden, B.S. ’90, biological sciences, works hard to prevent the kind of life-changing damage suffered by one of her earliest patients.

During her second year of medical school, Golden took the health history of a Type 1 diabetic patient who had experienced vision loss, kidney failure and a partial amputation—all of those complications staggering considering he was only in his mid-30s. The impact diabetes had on his life changed Golden and has been a driving force behind her life ever since.

Golden has spent her career advancing diabetes care, examining its connection to complications and other conditions, including depression and cardiovascular disease. Depression rates tend to be higher among individuals with lower socio-economic standing or less education; the same population also tends to have higher rates of diabetes because of lack of access to health care.

“Seeing patients has informed my research career all along,” says Golden, who is also director of the Inpatient Diabetes Management Service at The Johns Hopkins Hospital and executive vice-chair of the Department of Medicine. “Depressive symptoms are very prevalent in the population I take care of and often they can be a barrier to treatment.”

A prolific researcher, she seeks to understand both the biological and behavioral factors that make diabetes the nation’s seventh leading cause of death. Much of Golden’s research focuses on how hormones influence the development of diabetes. Those with chronic depression or anxiety—which elevate cortisol and adrenaline levels—have an increased risk of developing the disease. In one study, Golden found the risk emerges just three and a half years after first reporting depressive symptoms.

Because diabetes care requires daily commitment and a high level of patient engagement, Golden believes a patient’s life story can be as important to success as his or her health data. Making that daily commitment easier for patients is one of the Golden’s long-term goals. She’s working to create collaborative care models that group different providers together to streamline care and cut down on patient costs, lost work and hassle.

Golden won Johns Hopkins’ 2015 Innovations in Clinical Care Award for her role in reducing the rate of hypoglycemia—low blood sugar—in hospitalized patients with diabetes. During a three-year period, a committee Golden chaired instituted changes to create a nurse-led treatment protocol for hypoglycemia, and provide education and training for the hospital’s nurses to become experts in diabetes policies and glucose management. The committee also launched a uniform electronic ordering system based on new clinical standards.

While her love for research started before college, with parents who “let me grow algae and all those kinds of things in the kitchen and learned along with me,” her passion for research took off at UMD, in large part thanks to faculty advisor William Higgins, now associate professor emeritus of biology. Higgins pushed her to test herself in preparation for medical school.

“He almost threatened my perfect GPA,” she jokes now.

In addition to anatomy and other classes that gave her new perspective on would-be patients, Golden also credits UMD with connecting her to the National Institutes of Health. She spent two summers there as a research intern before attending medical school and eventually earning a master’s of health science.

Neil Brayton

Bridging the Gap in Oral Health Care

After spending a few years unhappy with his own smile, a young Neil Brayton, B.S. ’66, zoology, finally received the dental repairs that allowed him to put his best face forward.

After spending a few years unhappy with his own smile, a young Neil Brayton, B.S. ’66, zoology, finally received the dental repairs that allowed him to put his best face forward.

His renewed confidence led him to consider a career in dentistry, a field where he has spent more than four decades improving patients’ physical health and mental well-being.

Brayton works in private practice in Chestertown, Maryland. A self-proclaimed country dentist, he also supports Crossroads Community, a nonprofit organization providing psychosocial rehabilitation services to adults with persistent mental illness.

Each week, he treats one or two Crossroads clients—many who are transitioning from homelessness or living in poverty. The program is now supported by a grant, but Brayton began as a volunteer who appreciated the charity’s efforts to help those with mental needs remain in their communities.

This population often overlooks its dental health, Brayton explains, and high smoking rates complicate threats associated with poor dental hygiene. He encounters high rates of periodontal disease and performs fillings and extractions as needed.

“It’s a great inhibitor if you can’t or won’t smile,” says Brayton, also noting that pain associated with dental issues can be limiting as well. “I can take them out of the pain they have after years of neglect. That’s a nice feeling to be able to do that for someone.”

Brayton was recruited to the University of Maryland as a basketball standout and played three years with friend Gary Williams, who later spent 22 years as the team’s head coach.

But he might have gone to another school had coach H.A. “Bud” Millikan not reassured Brayton he would be able to complete his pre-dental requirements. During the 1964-65 season, the team went 18-8, and Brayton spent up to 30 hours a week in class, much of that time in labs.

He took summer courses to lessen his course load during fall and spring semesters and kept his eye on dental school admission policies.

In 1970, he earned his D.D.S. from the University of Maryland School of Dentistry. He was then drafted as an Army dentist during the Vietnam War, attaining the rank of major and receiving the Army Commendation Medal for meritorious service.

When he returned to the United States, Brayton went to work in Chestertown, the seat of Kent County with a population just over 5,000. Many of the staff members he started with 43 years ago still work with him today.

While the team has stayed together over the years, they have moved forward with the times, helping the practice usher in major advances in dental technology. These advances in technology and preventative care have made a huge difference. Where once Brayton might have fit two patients for dentures each week, he now fits just two pairs a month. That’s a reflection of how better detection and treatment can greatly improve a person’s oral health, he says.

Brayton doesn’t want anyone to be denied proper dental care due to cost or lack of access. In addition to his work with Crossroads, he volunteers annually with Missions of Mercy to treat low-income, high-need patients in other Maryland cities like Salisbury and Cumberland.

One of his dental hygienists also performs exams for students in Kent and Queen Anne’s county schools. She refers those who need more extensive care to the practice.

“I know firsthand what a difference dental care can make in a person’s life, and I’m happy that over the years I have been able to help a lot of people who couldn’t afford it,” says Brayton.

Margaret McCahill

Teaching Health Care as a Human Right

Arguments about the “health care crisis” aren’t just politics to Dr. Margaret McCahill, B.S. ’76, zoology.

As a child growing up in Los Angeles, she watched her single mom struggle to keep four young children healthy—a challenge managed mostly by volunteers at various free clinics.

Forty years later, the compassion she works to instill in others is inextricably linked to her own life experiences. As a family physician and founding director of a joint residency program combining family medicine and psychiatry, her mission is to serve medically indigent patients, particularly those in communities with less access to quality health care.

“For me, it’s always been about serving people who have trouble getting access to health care,” McCahill says. “It’s really a terrible problem. If you don’t have access to health care, nothing else really works to bridge the gap, not even other government programs.”

McCahill credits her successes to her supportive husband, as well as advisor William Higgins, who encouraged her to pursue a pre-med degree instead of completing an associate’s degree in nursing. Though McCahill was busy raising two young children, Higgins saw her potential and helped her arrange courses to complete her undergraduate studies quickly.

From her first residency in Cleveland, she witnessed the impact mental health had on her case load. After a move to California in the mid-1980s, McCahill decided to complete a second residency in psychiatry and merge her two passions.

Over the years, she has volunteered at a free clinic for the homeless, cared for Navajo patients who lived on nearby reservations, and tried to stop routine medical needs from exploding into health crises due to lack of health insurance.

“Small things become big things,” McCahill says, recounting the story of a patient in her mid-50s who put off seeing a physician for so long that she died of diabetes and hypertension-related kidney failure within a few weeks of being diagnosed. “Even with a sliding scale, the costs add up.”

As medical director of St. Vincent de Paul Village in San Diego for 10 years, McCahill had a unique opportunity to offer intervention and education. In addition to treating patients in the office—where staff resources were available for physical and mental health care—the team ran a mobile clinic stationed in church parking lots across the city.

She still remembers the single mother of four—a patient not unlike her own mom—who presented with colon cancer.

“Once you are identified with a life-threatening problem, you get access. But you have the burden of proving that life-threatening condition,” McCahill says. “Without us, those four kids would have been orphaned.”

The family-medicine/psychiatry residency program at UC San Diego also allowed McCahill to show young medical students, nurses and pharmacists why some patients put off care, whether because of cost or mental health issues.

“We would see so many extraordinary things,” says McCahill. “It’s just a crime that people go untreated. It’s not only proximity. It’s who’s willing to see whom under which payment plans.”

Though she’s no longer treating patients directly, McCahill remains on the faculty at the UC San Diego School of Medicine and the University of San Diego Hahn School of Nursing and Health Science. Since earning her master’s degree in theological studies this spring, she plans to teach spirituality and health—yet another way to foster mind-body connections.

As a Coast Guard wife, McCahill is also committed to serving active duty military members. She and her golden retriever, Portia, volunteer with Paws’itive Teams, an organization that helps those with post-traumatic stress, anxiety and medical issues regain comfort with real-life situations like grocery shopping.

Paul Corcoran

‘Euphoria’ in Public Service

Fascinating experiences with “superstar teachers” put Dr. Paul Corcoran, B.A. ’68, sociology, on the path to dental school at the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

Fascinating experiences with “superstar teachers” put Dr. Paul Corcoran, B.A. ’68, sociology, on the path to dental school at the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

The late A. James Haley, zoology professor, stood head-to-head at the microscopes with the students in his histology class, quizzing them about what they were seeing. James Huheey, now professor emeritus of chemistry and biochemistry, often stretched his office hours to help those who were struggling.

Though he’s now firmly past retirement age, Corcoran strives to follow the examples of these men, extending the same type of kindness as he serves Vail, Colorado’s year-round residents who are the community’s backbone. Among his regular clients and pro bono cases are many local carpenters and ski pros.

“My wife and I believe in treating everybody who walks through the door the same way,” says Corcoran, whose wife, Jean, a former kindergarten teacher, has been the manager of his practice for the last decade. “I’ve been blessed far beyond what I had the right to expect in my life. We love what we do, to try and really touch people’s lives.”

Together, the Corcorans founded Free Day of Dentistry for the community nine years ago. The nonprofit organization offers free dental care to adults one day each October, with everyone on the office staff volunteering to help community members in need.

In a single day, Corcoran has treated as many as 65 patients in need of cleanings, fillings and extractions. Most of them would otherwise be unable to pay for the basic, but necessary, procedures.

Though he does his share of high-end procedures, Corcoran hasn’t stayed in the field all these years simply to polish perfect smiles. He’s on-call year-round at the 60-bed Vail Valley Medical Center to respond to traumatic injuries—many from downhill skiing accidents—and life-threatening oral health issues.

“I had a young man last summer with a toothache that blossomed into a jaw infection,” recalls Corcoran. “The doctor told me he was 36 to 48 hours from death. But after a week in the hospital, he was able to return home.”

In 2012, the medical center honored Corcoran for his years of dedicated service helping patients during all hours in the center’s emergency department.

Corcoran also accepts referrals from local churches and other community organizations to serve at-risk patients throughout the year, including young people who have destroyed their teeth through drug or alcohol abuse.

“There’s such a euphoria when you do good and help people,” Corcoran says.

Written by Kimberly Marselas

See Also:

- Aspiring Humanitarians: Meet four University of Maryland undergraduates who plan to pursue careers in medicine.

- Supporting Aspiring Humanitarians: The University of Maryland's Reed-Yorke Health Professions Advising Office is dedicated to helping students who want to pursue a medical career after college.

- Terp Family Dental Practice is All Smiles: Meet the mother-and-daughters trio of Terps at At St. Mary’s Dental.

This article was published in the Fall 2016 issue of Odyssey magazine. To read other stories from that issue, please visit go.umd.edu/odyssey.