Restoring Island-Ocean Connections Benefits Humans, Wildlife and Marine Environments

New research highlights the critical link between island and marine ecosystems, as well as the importance of coordinated conservation efforts.

A multi-institutional team of researchers found that restoring and rewilding islands decimated by damaging invasive species benefits not only terrestrial ecosystems but also coastal and marine environments. According to the team, which includes University of Maryland scientist Daniel Gruner, the link between land and sea significantly impacts ocean health, biodiversity, climate resilience and human wellbeing—factors that suggest conservation efforts should address the interconnectedness of all ecosystems rather than simply pursuing individual pieces through siloed efforts. Their paper, “Harnessing island-ocean connections to maximize marine benefits of island conservation,” was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) on December 5, 2022.

“Indigenous cultures on islands managed watersheds from ‘ridge to reef,’ recognizing that land use has consequences for the sustainability of coastal ecosystems downstream,” explained Gruner, who is an associate professor of entomology at UMD and a co-author of the paper. “We’re adapting this approach to improve our conservation efforts by targeting these connections between land and sea.”

“By applying this knowledge to islands worldwide, we can understand the marine benefits of island restoration projects and maximize returns for our conservation management investments for people, wildlife and the planet,” said Stuart A. Sandin, lead author of the paper and a marine ecologist at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego.

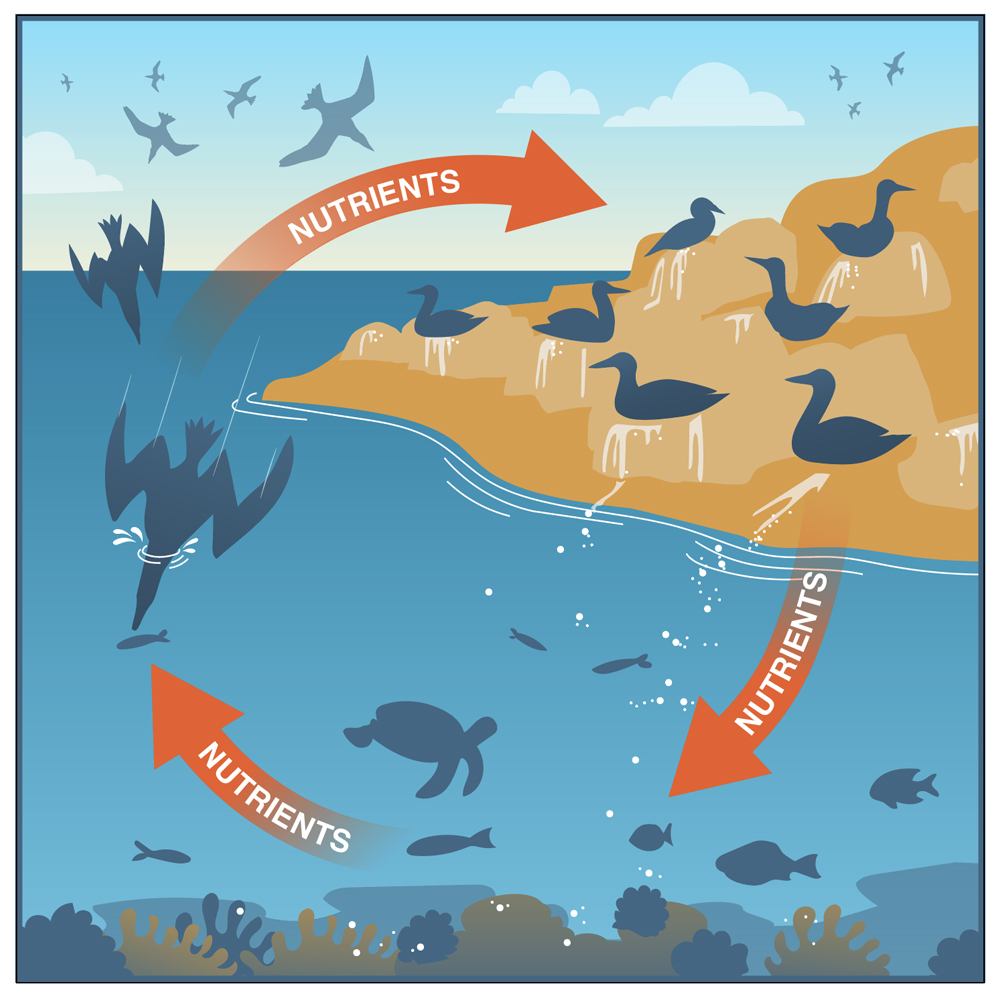

Islands support some of the most valuable ecosystems on Earth, nurturing a disproportionate amount of rare plants, animals, communities and cultures found nowhere else. Healthy land-sea ecosystems depend on a flow of nutrients from oceans to islands and from islands to oceans. This natural flow is facilitated by “connector species,” such as seabirds, seals and land crabs. Research shows that islands with high seabird populations, for example, which feed in the open ocean and bring large quantities of nutrients to island ecosystems through their guano deposits, are associated with larger fish populations, faster-growing coral reefs and increased rates of coral recovery from climate change impacts.

Many seabird species, however, have been driven to local or global extinction or near-extinction due to invasive non-native mammals, such as rats that eat bird eggs and young hatchlings on islands where they nest. The loss of these connector species populations often results in ecosystem collapse, both on land and in the sea. Researchers found that removing invasive species from islands is one of the most effective methods for restoring native plants, animals and ecosystems.

“Invasive mammalian species, like rats, wild European boars and mongooses, have a disproportionate negative impact on endemic island communities that don’t have natural defenses against them. Restoring the islands to how they were before these invasive species were introduced is one of the most effective methods to protect and improve ecosystems on land,” Gruner said. “We now know that we can link those benefits to marine ecosystems, so it’s a chance to protect and restore both islands and coasts.”

The research team also discovered that islands with higher rainfall, lower wave energy (calmer tides) and other conditions consistent with high land-sea connectivity could produce substantial marine co-benefits after invasive species removal and island rewilding.

One candidate with such features was Floreana Island, located in Ecuador’s Galapagos Archipelago. Though indigenous tortoises once existed on the island, they were particularly vulnerable to invasive predators and were declared extinct. As a result, the island’s terrestrial and marine ecosystems fell into an imbalance without the tortoises’ ecological role as grazers impacting native plant life.

Another site with high land-sea connectivity potential was Sonsorol Island, Palau, an island nation located in the Pacific. Because of the island’s geographical remoteness, residents primarily relied on local resources available to them. Prior to the impacts of invasive species, the community lived harmoniously with their environment and thrived on the natural resources provided by the land and sea. However, the significantly reduced seabird population due to invasive species significantly slowed nutrient deposition, which in turn limited the productivity of surrounding coral reefs.

To help address the needs of island ecosystems and human residents, the researchers collaborated with non-profit conservationists, government agency representatives, island communities and other stakeholders to develop new guidelines to shape where the most impactful marine co-benefits of island restoration could occur. Based on their findings from islands like Floreana and Sonsorol, their new model highlights six essential environmental characteristics that may help guide prioritization of island-ocean restorations: precipitation, elevation, vegetation cover, soil hydrology, oceanographic productivity and wave energy.

Both the Sonsorol and Floreana island restoration projects are part of an ambitious new environmental campaign called the Island-Ocean Connection Challenge, which aims to restore and rewild at least 40 globally significant island ecosystems to benefit islands, oceans, and communities by 2030. For decades, residents of the islands have witnessed the negative effects of invasive species firsthand; now they are able to actively shape their homes’ future by playing a central role in the islands’ restoration.

“There are still relatively few studies that document strong land to sea impacts,” Gruner said. “We hope that this paper will help stimulate more research looking into that critical link between terrestrial and marine ecosystems, which can ultimately help stakeholders prioritize where to allocate our limited resources and conservation efforts.”

###

The paper, “Harnessing island–ocean connections to maximize marine benefits of island conservation,” was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) on December 5, 2022.

This press release was adapted from text provided by Island Conservation.

This research was supported by the Island Conservation Board of Directors, the Center for Marine Biodiversity and Conservation at Scripps, the Nature Conservancy California Chapter, the Leo Model Foundation and the Archie Arnold Trust.