NASA/UMD Researchers Take to the Air to Clock Wildflower Blooms

A study led by a researcher at NASA and the University of Maryland is revealing there’s more to flowers than meets the human eye.

The recent analysis of wildflowers in California shows how aircraft- and space-based instruments can use color to track seasonal flower cycles. The results suggest a potential new tool for farmers and natural-resource managers who rely on flowering plants.

In their study, published last month in Ecosphere, the scientists surveyed thousands of acres of nature preserve using a technology built by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in California. The instrument, an imaging spectrometer, mapped the landscape in hundreds of wavelengths of light, capturing flowers as they blossomed and aged over the course of months.

For many plant species from crops to cacti, flowering is timed to seasonal swings in temperature, daylight and precipitation. Scientists are taking a closer look at the relationship between plant life and seasons—known as vegetation phenology—to understand how rising temperatures and changing rainfall patterns may be impacting ecosystems.

Typically, wildflower surveys rely on boots-on-the-ground observations and tools such as time-lapse photography. But these approaches cannot capture broader changes that may be happening in different ecosystems around the globe, said lead author Yoseline Angel, a scientist at UMD’s Earth System Science Center (ESSIC) and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

“One challenge is that compared to leaves or other parts of a plant, flowers can be pretty ephemeral,” she said. “They may last only a few weeks.”

It was the first time the instrument had been deployed to track vegetation steadily through the growing season, said David Schimel, a research scientist at JPL. The study included additional researchers from ESSIC and Goddard as well as from Morgan State University and the University of California, Los Angeles.

To track blooms on a large scale, Angel and other NASA scientists are looking to one of the signature qualities of flowers: color.

Flower pigments fall into three major groups: carotenoids and betalains (associated with yellow, orange and red colors), and anthocyanins (responsible for many deep reds, violets and blues). The different chemical structures of the pigments reflect and absorb light in unique patterns.

Spectrometers allow scientists to analyze the patterns and catalog plant species by their chemical “fingerprint.” As all molecules reflect and absorb a unique pattern of light, spectrometers can identify a wide range of biological substances, minerals and gases.

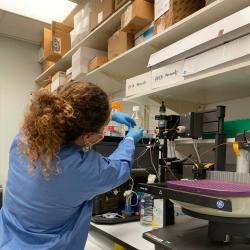

Handheld devices are used to analyze samples in the field or lab. To survey moons and planets, including Earth, NASA has developed increasingly powerful imaging spectrometers over the past 45 years. One such instrument is called AVIRIS-NG (Airborne Visible/InfraRed Imaging Spectrometer-Next Generation), shown below, which was built by JPL to fly on aircraft.

The scientists developed a method to tease out the spectral fingerprint of the flowers from other landscape features that crowded their image pixels. In fact, they were able to capture 97% of the subtle spectral differences among flowers, leaves and background cover (soil and shadows) and identify different flowering stages with 80% certainty.

The results open the door to more air- and space-based studies of flowering plants, which represent about 90% of all plant species on land. One of the ultimate goals, Angel said, is to support farmers and natural resource managers who depend on these species along with insects and other pollinators in their midst. Fruit, nuts, many medicines and cotton are a few of the commodities produced from flowering plants.

Angel is working with new data collected by AVIRIS’ sister spectrometer that orbits on the International Space Station. Called EMIT (Earth Surface Mineral Dust Source Investigation), it was designed to map minerals around Earth’s arid regions. Combining its data with other environmental observations could help scientists study superblooms, a phenomenon where vast patches of desert flowers bloom after heavy rains.

This article is based on an original text by Sally Younger of NASA’s Earth Science News Team.