Lower Winter Losses, But Tough Times Linger For Honey Bees

. beekeepers lost more than one in five honey bee colonies in the winter of 2013-2014—significantly fewer than the winter before. But tough times continue to linger for commercial beekeepers, who are reporting substantial honey bee losses in summer as well. Beekeepers who tracked the health of their hives year-round reported year-to-year losses of more than one in three colonies between spring 2013 and spring 2014.

Those are the key findings of an annual national survey of honey bee colony losses, conducted by the Bee Informed Partnership with the Apiary Inspectors of America and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Dennis vanEngelsdorp, an assistant professor of entomology at the University of Maryland and the director of the Bee Informed Partnership, led a team of 11 researchers who conducted the survey. A total of 7,183 beekeepers, who collectively manage about 22 percent of the country’s 2.6 million commercial honeybee colonies, took part.

The survey is part of a research program aimed at understanding nearly a decade’s worth of high death rates in managed honey bee colonies. The losses impose heavy costs on beekeepers and could lead to shortages of some crops that depend on honey bees for pollination.

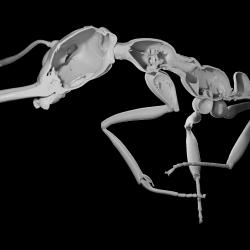

No single culprit is responsible for all the honey bee deaths. But the Bee Informed Partnership’s research shows mortality is much lower among beekeepers who carefully treat their hives to control a lethal parasite called the varroa mite.

“If there is one thing beekeepers can do to help with this problem, it is to treat their bees for varroa mites,” vanEngelsdorp said. “If all beekeepers were to aggressively control mites, we would have many fewer losses.”

Beekeeping is not only a backyard hobby, but a linchpin of the food supply. Farmers depend on honeybees and other pollinators to fertilize valuable crops, from apples and almonds to tomatoes and watermelons. The pollination provided by honey bees adds about $15 billion to the value of U.S. crops.

The survey found that 23 percent of the managed honeybee colonies in the U.S. died between Oct. 1, 2013 and March 31, 2014. That’s well below the average loss of 30 percent over the survey’s history.

But summer death rates were nearly as high as the winter ones. Over the summer, about 20 percent of survey respondents’ colonies died. Losses between spring 2013 and spring 2014 averaged 34 percent.(The winter and summer losses do not match up to the year-to-year losses because not all beekeepers filled out all sections of the survey.)

“Rising and falling rates of colony losses demonstrate how complicated the issue of honey bee health has become,” said Jeff Pettis, a survey co-author and research leader of the USDA’s Bee Research Laboratory in Beltsville, Md. Pettis pointed out that the causes of honey bee colony failures are complex, including varroa mites, other parasites and viruses; poor nutrition, which can be due to a shortage of wildflowers in herbicide-sprayed or drought-stricken farm fields; and exposure to insecticides and fungicides.

Now in its eighth year, the survey originally focused on winter mortality in managed honey bee colonies. The generation of bees that lives through the winter must survive months longer than summer bees’ 30-day lifespan. In winter, honey bees don’t produce offspring and are confined in a hive where diseases can spread.

“We used to think winter was the critical period,” vanEngelsdorp said. “But during our field studies, beekeepers told us they were also losing colonies in the summer months. So we expanded the survey and found that in fact, colonies are dying all year round.”

About two-thirds of beekeepers surveyed, who ranged from hobbyists to large businesses, said their colonies suffered unacceptable losses—greater than the 19 percent mortality rate that, on average, they were willing to absorb. It was the second year in a row that most beekeepers reported unacceptably high mortality.

The beekeepers were asked to list the probable causes of their losses; and in a separate survey, some also described how they managed their hives. Those responses are still being analyzed. But an initial review, fieldwork and past surveys all point to varroa mites as a persistent—and controllable—problem.

Every beekeeper needs to have an aggressive varroa management plan in place,” vanEngelsdorp said. “Unfortunately, many small-scale beekeepers are not treating their bees, and are losing many colonies. And those colonies are potential sources of infection for other hives.”

This survey was conducted by the Bee Informed Partnership, which receives a majority of its funding from the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, USDA (award number: 2011-67007-20017). The content of this article does not necessarily reflect the views of the USDA.

Dennis vanEngelsdorp home page

Bee Informed Partnership

A summary of the 2013-2014 survey results is available at http://beeinformed.org/results-categories/winter-loss-2013-2014/.

Media relations contact: Heather Dewar, 301-405-9267, hdewar@umd.edu

Writer: Heather Dewar

University of Maryland

College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences

2300 Symons Hall

College Park, MD 20742

www.cmns.umd.edu

About the College of Computer, Mathematical and Natural Sciences

The College of Computer, Mathematical and Natural Sciences at the University of Maryland educates more than 7,000 future scientific leaders in its undergraduate and graduate programs. The college’s 10 departments and more than a dozen interdisciplinary research centers foster scientific discovery, with annual sponsored research funding exceeding $150 million.