Meet UMD Entomology Graduate Student Jenan El-Hifnawi

Jenan El-Hifnawi (B.S. ’22, biological sciences) is a master’s student in the University of Maryland’s Department of Entomology.

How did you get interested in entomology?

In my search for research opportunities, I stumbled upon the U.S. Geological Survey Bee Lab in Laurel, Maryland, where I did a project exploring which flowers bumble bees visit. The project gave me the opportunity to spend lots of time looking closely at bees and other insects, and I fell in love! Bugs are truly so cool—they are so incredibly diverse and widespread. If you’re entertained by bugs, you’ll be entertained basically anywhere!

Why did you decide to stay at the University of Maryland for graduate school?

During undergrad, I had lots of amazing opportunities to do research both at the university and at nearby institutions. I was fortunate to have great mentors at UMD and in the surrounding area, including [Entomology Associate Professor] Anahí Espindola, who hired me as a lab technician and encouraged me to apply for a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (GRFP).

While working in Anahí’s lab and collaborating with her on the GRFP application, I grew incredibly appreciative of her mentorship and values as a person and scientist. I wanted to expand my horizons with a different research focus in grad school, but I also prioritized having a principal investigator who I know is kind, fair and has an advising style that suits me.

Tell us about your research.

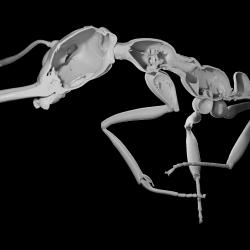

I’m conducting a phylogeographic study of four species of Andean bees found in the Andes mountains to understand how they responded to the peak of the last ice age, approximately 20,000 years ago, known as the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM). During this time, bees encountered changes and challenges, including the separation of species by a glacial sheet and shifts in species diversity due to changes in habitat suitability.

To study how the LGM impacted the ranges and relationships within these four species, I am combining genomic data from ultra-conserved element (UCE) sequencing for each species with species distribution models (SDMs) to identify potential spatial evolutionary histories.

UCEs are regions of the genome that are highly conserved across evolutionarily distant taxa. They are a valuable tool in genomics because they facilitate the sequencing of a large number of samples more cost-effectively than whole-genome sequencing, and they simplify analysis, especially when no reference genome is available. UCEs are also great for museum DNA because they work well with highly fragmented DNA. This was important given that most of my sampling is from museums, like the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History and the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

SDMs are used to understand the suitability range for a species. They identify which climatic conditions were suitable for the species from 20,000 years ago to today.

From the UCE and SDM data, I will identify the most likely evolutionary history for these four species of bees.

Why is your research important?

Despite the immense biodiversity of the Andes mountains, the forces responsible for generating this biodiversity are poorly understood, especially in the southern Andes. Understanding these processes is crucial for protecting bee species. While I believe it's important to conserve biodiversity by conserving species, it's important to recognize that conservation of species is like conserving a snapshot in time. Species are constantly evolving and shifting their ranges, so understanding the processes that generate biodiversity is important to ensuring biodiversity can continue to exist and evolve.

Another reason this research is important is that one of the species I’m studying, Bombus dahlbomii, is an endangered species, so information about its genetics and phylogeographic history can be used to inform its conservation efforts.

What do you want to do when you finish your degree?

I’d love to work for the federal government (maybe the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) and conduct research related to pollinator management. I would really enjoy using the tools I’ve worked with in my master’s (e.g., phylogenomic tools, population genomic tools and SDMs) to inform conservation efforts, including pollinator plantings. I love working with these types of data and analysis, and I would be thrilled to get to see the analyses inform conservation decisions. I believe that rewilding landscapes with native plants is one of the most impactful things we can do to restore ecosystems, and I also believe it provides incredible educational opportunities. I would also love to bring in local communities to interact with rewilded landscapes.

What advice would you give to someone interested in this field?

It’s easy to feel like you should know what you want to study very early in your career. While many folks do have specific research interests they want to pursue, many others, including myself, are still figuring out exactly what we’ll spend the rest of our lives doing. Saying yes to a broad range of opportunities is the best way to figure out what works for you while gaining valuable and diverse skills. Don’t beat yourself up for not having it all figured out, and just keep working hard on whatever opportunities that come your way and pique your interest.

Written by Muntaha Hossain