Finding the Future of Medicine

Stephanie Galanie (B.S. ’10, biochemistry; B.S. ’10, biological sciences) shares how her years at UMD shaped her path to success in synthetic biology and analytical chemistry.

Since graduating from the University of Maryland, Stephanie Galanie (B.S. ’10, biochemistry; B.S. ’10, biological sciences) developed a passion for two things: bread and wine.

As an avid baker and wine enthusiast, Galanie loves experimenting with different flavors and dimensions in her baked goods and drinks. Her knowledge of grape-growing and winemaking earned her a Level 3 Award in Wines from the Wine & Spirit Education Trust, an advanced certification for wine industry professionals and enthusiasts alike.

As a trained chemist, however, Galanie’s passion for bread and wine is driven by her fascination with the mechanisms responsible for creating them. She has studied fermentation extensively and remains enthralled by how transformative the process can be.

“My dissertation topic was on synthesizing yeast to make medicinal products, which basically means redesigning yeast in a way that lets us develop new and beneficial uses for it,” explained Galanie, who earned her Ph.D. in chemistry and M.S. in bioengineering at Stanford University. “With that project, I saw the potential in using processes like fermentation to make novel life-changing medicines and treatments—ones that could fundamentally innovate the way we currently create drugs.”

Galanie’s success in engineering yeast to quickly and cost-effectively produce pain-killing compounds with fewer addictive properties led her to explore other biosynthetic approaches to improving human health and quality of life.

So far, she helped develop pest and pathogen-resistant feedstock crops as a fellow at Oak Ridge National Laboratory and engineer an enzyme platform that resulted in a new stevia-based sweetener for commercial food products as a scientist at Codexis, a protein engineering company based in San Francisco.

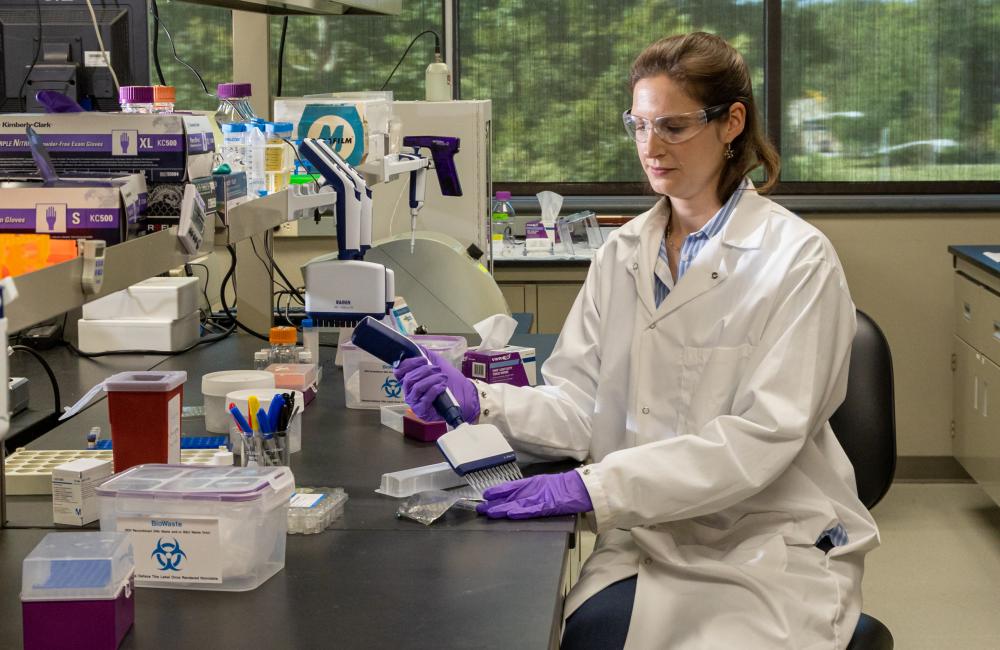

Today, Galanie is director of protein engineering at Merck, where she continues to explore new ways to solve problems with synthetic biology and analytical chemistry. Galanie believes that the answers to many medical mysteries lie in the biochemical makeup of microorganisms—and that it’s her job to find those answers.

“Protein engineering is still a relatively young scientific discipline and it’s a field that’s growing rapidly,” Galanie said. “I wouldn’t have been able to predict that I’d be a protein engineer when I first graduated, but I’m not too surprised that I’m here where I am and doing what I do now.”

Pursuing passions

Although Galanie initially majored in chemical engineering at UMD, she switched to biochemistry after a summer internship with the Molecular Neuropharmacology Section at the National Institutes of Health in 2007. There, she learned about stress, addiction and other neuropsychiatric disorders at the cellular level while studying dopamine receptors—her first real taste of the role chemistry plays in living organisms.

“I was basically bitten by the biochem research bug after that,” Galanie explained. “I changed my major and never looked back.”

Galanie’s Gemstone Honors team researched the effects of natural products from herbal supplements on human breast cancer proliferation and gene expression. Around the same time, Galanie worked on her departmental honors thesis in the lab of UMD Professor Emeritus of Chemistry and Biochemistry Philip DeShong. There, Galanie explored drug delivery systems based on mesoporous silica nanoparticles and their potential diagnostic and therapeutic uses in medicine.

These experiences eventually sparked Galanie’s Ph.D. dissertation on medical applications of yeast and a genuine appreciation for interdisciplinary research. The diversity of backgrounds, thoughts and ideas she experienced at Maryland enriched her own approaches to problem-solving—a vital aspect of protein engineering, which draws on extensive knowledge of biology, chemistry, immunology, genetics, material science and more. Knowing how to communicate and collaborate were also important elements of her journey from College Park to Merck.

“What I really love most about chemistry and about my current job is getting the chance to work with hardworking, smart people from different backgrounds. Having a diverse team that gets together and creates something that has value to society is really fulfilling to me,” Galanie said. “I found it in my STEM classes growing up and I found it at UMD, too.”

Continuing to explore

As director of protein engineering at Merck, Galanie works at the forefront of medical advances and solutions. She believes that synthetic biology, particularly protein design and development, will continue to be a major trend in the world of biopharmaceuticals, especially with the rise of vaccines that use messenger RNA, a type of single-stranded RNA necessary for protein production.

“Protein synthesis isn’t really a completely new concept,” Galanie explained. “For example, insulin was the first protein we industrially synthesized. We used to have to extract and isolate insulin from animals, but now we can create it inside a manufacturing facility using microorganisms like yeast and bacteria. By being able to synthesize insulin and proteins this way, we’re not only saving environmental resources but also increasing access to life-saving compounds for millions of people.”

Galanie noted that the COVID-19 vaccine was a similar advancement in the medical sector, as the first mRNA vaccine to complete clinical trials and be used in humans. The new technology allowed millions to access protection against the virus, a feat that would have taken much longer if the technology didn’t exist.

“Because it’s a relatively fast-paced environment, I’m lucky to see a lot of the tech that my team has developed come to fruition,” Galanie said. “We’re always working with the entire R&D organization, across all disciplines, to come up with better ways to improve treatments and vaccines across all therapeutic areas, so it’s very rewarding to see our projects progress and impact patients.”

Looking back at her experiences at UMD, Galanie offered this advice for students interested in a career in chemistry: “The first thing you do out of school is probably not what you’re going to do for the rest of your life, so consider it a chapter, not the end. Keep learning and exploring. Different solutions need different people and experiences. We need everyone—all different thinkers and problem-solvers—to work together to bring life-changing solutions to everyone.”