UMD’s Physics Frontier Center Renewed by National Science Foundation

Center scientists conduct cutting-edge quantum physics research and provide educational opportunities for students and the public

The National Science Foundation (NSF) renewed its support for the Joint Quantum Institute’s (JQI) Physics Frontier Center with a new five-year grant. JQI is a partnership between the University of Maryland and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), with support from the Laboratory for Physical Sciences.

Established in 2008 with a five-year, $12.5 million grant, JQI’s Physics Frontier Center supports researchers in atomic and condensed matter physics. The center also hosts physics public outreach programs, including a hands-on summer program for high school students. UMD Physics Professors and JQI Fellows William Phillips and Luis Orozco co-direct the center, which is one of 10 in the country.

“The Physics Frontiers Centers truly are unique environments for both research and education,” said Jean Cottam Allen, NSF program director for the Physics Frontiers Centers. “We’re excited about these new awards and look forward to the great impacts these groups will have.”

Researchers in JQI’s Physics Frontier Center have made many scientific discoveries since the center’s launch. And strong collaborations have formed between condensed matter and atomic, molecular and optical physicists, exposing young researchers to the rich and exciting science that lies at the intersection of these two physics sub-fields.

During the next five years, the researchers will continue to explore cutting-edge topics that connect atomic, molecular, optical and condensed matter physics. Specifically, they will focus on investigating topological quantum matter, entanglement in many-body atomic ensembles and dynamics in systems far from equilibrium.

“Our work sometimes has to do with practical things. It always has to do with really fundamental quantum mechanical problems and with understanding more clearly the way the world works,” said Phillips, a College Park Professor in Physics who shared the 1997 Nobel Prize in physics for using laser light to cool and trap atoms.

Many of the center’s scientists, like Assistant Professor of Physics Gretchen Campbell, are conducting basic research aimed at advancing our understanding of the quantum world. Campbell, who is also a JQI Fellow, is a pioneer in atomtronics, an emerging field in which scientists use ultracold atoms to build circuits with the same superconducting properties as some electronic circuits.

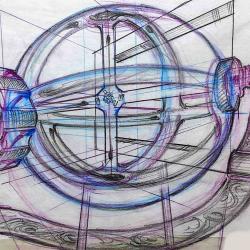

Campbell’s work could lead to a quantum counterpart for today’s inertial sensors, which are critical components in instruments that measure acceleration, rotation and other kinds of motion. Much of the technology in our daily lives relies on inertial sensors, including smartphone compass apps, video camera image-tracking mechanisms and aircraft navigational systems. Quantum inertial sensors may guide planes and submarines more accurately, and therefore more safely.

“The research is in the earliest stages,” said Campbell, who won a Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers in December 2013. “It’s possible there are other atomtronic sensors that will be useful.”

Research conducted by NIST’s Ian Spielman and Physics Professor Victor Galitski, who are both JQI fellows, also has potential applications to atomtronic devices. The researchers caused a gas of atoms to exhibit an important quantum phenomenon known as spin-orbit coupling for the first time. Their technique has opened new possibilities for studying and better understanding fundamental physics, with potential applications to atomtronic devices, quantum computing and next-generation spintronics devices.

In 2010, Sankar Das Sarma, a Distinguished University Professor who holds the Richard E. Prange Chair in Physics, and colleagues proposed that by layering certain superconducting and semiconducting materials like a sandwich, researchers could create special particles, called Majorana fermions, which could act as qubits in a topological quantum computer. Preliminary proof-of-principle studies show these qubits can be made in lab conditions that are not as exacting as the ones needed for ion trap designs.

“You need low temperatures, but not anywhere near as low as other approaches, and a much lower magnetic field,” said Das Sarma, who is also a JQI Fellow. “We call this ‘generic topological computing,’ because it’s relatively easy to do.”

The next step is for experimentalists to build a prototype that reliably and clearly realizes Majorana fermions and then links some together to function as qubits. Vladimir Manucharyan, JQI Fellow and assistant professor of physics, plans to do just that.

“I find this approach fascinating because it involves fundamental questions of physics and new states of matter,” said Manucharyan. “It requires a lot of technical skills, but I think we can actually make it work.”

Christopher Monroe, JQI Fellow and Bice Zorn Professor of Physics, successfully performed quantum simulations of different phenomena, such as frustration and magnetism, using a network of trapped atomic ions. “Frustrated" ensembles of interacting components—those which cannot settle into a state that minimizes each interaction—may be the key to understanding a host of puzzling phenomena that affect systems from neural networks and social structures to protein folding and magnetism.

Scientists in the Physics Frontier Center say they are not only interested in potential applications, but also profoundly excited by the chance to explore the mysteries of the quantum realm.

“What appeals to me is understanding how things work and the underlying laws of nature,” said Jonathan Hoffman (Ph.D. '14, Physics), who worked with Orozco and JQI Co-director Steve Rolston in the center. “The idea of inventing something new is fascinating. But more important, I like exploring new ideas in physics.”

Writers: Heather Dewar and Abby Robinson

About the NSF Physics Frontier Centers Program

The overarching Physics Frontiers Centers program supports university-based centers and institutes where the collective efforts of a larger group of individuals can result in transformational advances in specific areas of physics, such as atomic, molecular, optical, plasma, elementary particle, nuclear, astrophysical, gravitational, accelerator and biological physics. Multidisciplinary projects involving related fields can also take place in these collaborative environments. Additionally, the centers include creative, substantive activities aimed at enhancing education, broadening participation of traditionally underrepresented groups and conducting outreach to the scientific community and general public. These awards are made for five years with a potential one-year extension. Open competitions are held every three years.