UMD Climate Researchers React to 2014’s Record-Breaking Global Temperatures

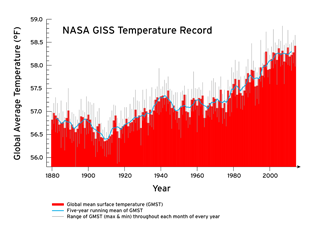

Global climate has made a lot of headlines in the last month. On Jan. 16, 2015, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and NASA jointly announced that 2014 is officially the hottest year on record since formal recordkeeping began in 1880. Less than a week later, on Jan. 21, the U.S. Senate voted 98-1 in favor of an amendment to the Keystone XL pipeline bill stating, “climate change is real and is not a hoax.” On Jan. 30, the results of a poll conducted by the New York Times, Stanford University and Resources for the Future found that the majority of Americans favor government action to address climate change. Most recently, on Feb. 10, the National Academy of Sciences released a pair of reports recommending further study of climate intervention (i.e., geoengineering) strategies.

To get some perspective on 2014’s record-breaking temperatures and what the announcement means for ongoing climate discussions, we reached out to a handful of University of Maryland climate researchers to get their take.

Antonio Busalacchi, professor of atmospheric and oceanic science and director of UMD’s Earth System Science Interdisciplinary Center (ESSIC):

“The temperature record for 2014 is more proof of the inexorable rise in global mean temperatures. But there’s a danger to engaging in a climate play-by-play, because the timescale of climate is on the order of a century. It’s like watching a baseball game and trying to make a prediction on the outcome of the game by watching only one play. It’s the larger scale pattern that matters.”

“This is not a large El Niño year, as was predicted. But that is not significant. In fact, that means that the warming we saw this year cannot be attributed solely to natural variability. The caveat always is that we are talking about global warming. This means there will always be some areas that are warmer and some that are cooler. But the overall average is warmer. This year, the U.S. was one of the cooler areas.”

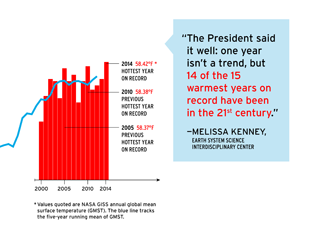

Melissa Kenney, assistant research professor at ESSIC and lead principal investigator of the U.S. Global Change Research Program National Climate Indicator System:

Melissa Kenney, assistant research professor at ESSIC and lead principal investigator of the U.S. Global Change Research Program National Climate Indicator System:

“The President said it well: one year isn't a trend, but 14 of the 15 warmest years on record have been in the 21st century. There has been such a dramatic shift from the 20th century baseline. We need strategies to mitigate the effects of warming and to make sure we’re prepared.”

“What we really need is an understanding of the planet’s vital signs, and how those climate signs impact the private sector and natural systems. But the real question is how we’ll respond to reduce our dependence on fossil fuels and manage the worst impacts, including heat stress, rising seas and acidifying oceans.”

“The 2014 announcement is a good reminder as to why we’re making these important decisions. A single indicator like this can make a great story, but it is not enough by itself to support decisions. Folks will hear the news and then ask, ‘How does this impact me and my community? How can I use this information to help make decisions?’ My work is focused on how we can translate complex scientific information into a broader range of indicators that people can use to make decisions, without being policy-prescriptive.”

Raghu Murtugudde, professor of atmospheric and oceanic science with an appointment at ESSIC:

“The 2014 temperature record is worth noting, with the caveat that people need to know what it really means. The U.S. had a miserable winter last year, and this year feels quite cold as well. Although the continental U.S. might feel cold, sometimes Fairbanks, Alaska is warmer than Washington.”

“Some say that global warming has slowed down. There is definitely a flattening of the trend, but we need to explain why record warm individual years still fit the pattern. We are very confident about carbon dioxide measurements, and we understand the physics of energy balance with increasing greenhouse gases. It is undeniable that humans are having an effect.”

“We are changing the planet’s energy balance. Even if there is a pause, we can be making winters and summers very extreme. In 2012 an El Niño event was predicted, but didn’t come. The same happened in 2014. Is El Niño itself changing? How is the planet budgeting energy? Is the Earth losing more energy to space or hiding it within the system? If the latter, where exactly is it hidden? How and when may it be re-released? These are the questions worth focusing on.”

Ross Salawitch, professor of atmospheric and oceanic science with co-appointments in the UMD Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry and ESSIC:

Ross Salawitch, professor of atmospheric and oceanic science with co-appointments in the UMD Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry and ESSIC:

“Focusing on one year makes headlines, so announcements like this get a lot of attention. But scientists analyze long-term patterns. In that context, 2014’s record temperatures are what we expected. If it had been slightly less than the prior record, that would have fit our expectations, too.”

“Climate is the average of weather. Climate is quantified on a computer, whereas people experience weather directly. To put this in perspective, the Northeast U.S. could have a big storm, but climatologically speaking it could still be a mild winter if other parts of the world are unusually warm.”

“With water, what goes up must come down. The balance must stay constant over time, with one exception—warmer air will hold more water. So warming means more water in the air globally. Under many global warming scenarios, I wouldn’t be surprised to see more intense precipitation, including snowfall, because there will be more water in the atmosphere.”

Media Relations Contact: Matthew Wright, 301-405-9267, mewright@umd.edu

University of Maryland

College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences

2300 Symons Hall

College Park, MD 20742

www.cmns.umd.edu

@UMDscience

About the College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences

The College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences at the University of Maryland educates more than 7,000 future scientific leaders in its undergraduate and graduate programs each year. The college's 10 departments and more than a dozen interdisciplinary research centers foster scientific discovery with annual sponsored research funding exceeding $150 million.