UMD Astronomy Alum Brings Space Images to Light

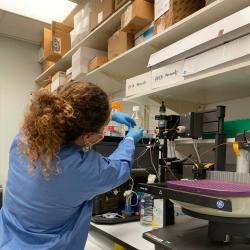

Alyssa Pagan (B.S. ’16, astronomy), a science visuals developer with the Space Telescope Science Institute, puts the color and sparkle in cosmic imagery.

Alyssa Pagan (B.S. ’16, astronomy) can’t tell you exactly when or where she first fell in love with space, but it was likely a cloudless evening in her youth.

“I have been interested in space ever since I could look up at the night sky,” Pagan said. “It was mind blowing for me to realize that all those points are stars, and those stars potentially have planets of their own.”

Years later, Pagan does a lot more than admire those stars from afar—she brings distant worlds to life as a science visuals developer with the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), the Baltimore-based organization that operates the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) and James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) in partnership with NASA.

Pagan transforms dark, monochromatic images into the dazzling displays of light and color seen on computers, phones and TV screens. Among her greatest hits: the “Cosmic Cliffs” of the Carina Nebula, one of the first JWST images published in 2022; a star-studded view of the “Pillars of Creation,” first popularized by Hubble but revisited nearly three decades later by JWST; and a snapshot of Galaxy NGC 1433, a barred spiral galaxy with young stars forming its swirling “arms.”

Though her job involves some artistic interpretation, Pagan explained that her role is less about “creating” an image and more about stripping away the shadows to bring cosmic marvels to light.

“I see myself as an art restorer because I'm revealing something that's already there,” Pagan said. “But since it’s my job, I sometimes forget the scale of things, so it's nice to take a step back and realize, ‘This is a deep-field image containing a galaxy that is 300 million years old.’”

That sense of wonder has taken Pagan far since she first discovered her career path at the University of Maryland.

Where art and science collide

Despite taking an early interest in space, Pagan didn’t set out to study science. In 2011, she earned her bachelor’s degree in art and design with a focus on traditional illustration—think “cell by cell, old-school Disney,” Pagan explained—from Towson University in Maryland. Still, she couldn’t shake the feeling that she should be doing something in the sciences.

“Once I graduated, I thought, ‘This is great, but I want more,’” Pagan said. “I felt like I could get more from college, so I decided to go back for astronomy.”

After taking community college classes for a while, Pagan transferred to UMD as an astronomy major in 2014. What started as a hunch became the perfect educational blend for her future job at STScI.

“I wasn’t thinking at the time about how my two interests—art and science—would come together,” Pagan said. “I just knew that I enjoyed art and I enjoyed science, so I wanted to learn about both.”

Pagan learned about her future career while taking an observational astronomy class taught by Department of Astronomy Chair and Professor Andrew Harris.

“I loved that class, and it’s where I realized that the position I have now—creating images from observatory data—was a thing that people do,” Pagan said. “We took observations of several objects, but the one I remember now is the Ring Nebula. It was cool to realize, ‘I took this data myself of something that exists lightyears away, and I’m able to detect it and show what it looks like.’”

After graduating from UMD in 2016, Pagan stayed in the department and worked as an office clerk and academic program specialist. When Pagan saw an opening for her current position at STScI, she applied with the department’s full support.

“Andy Harris was the person who helped me get my current job, and I’m very grateful,” Pagan said. “He knew that I was going to leave eventually to find my dream job at STScI. I didn’t think I really wanted to work anywhere else.”

Stretching and coloring

After joining STScI’s production team in 2019, Pagan primarily processed HST images until JWST’s launch in December 2021. As a visualizer, she works with data that has been captured by space telescopes, transmitted to Earth and then calibrated by scientists. At first glance, the resulting image isn’t much to look at.

“When I first bring that data into visualization software, it will appear black with maybe some white dots,” Pagan said. “That's because the sensitivity of these instruments is way beyond the capability of our displays.”

Pagan then “stretches,” or expands, the distribution of brightness values to illuminate any details left in the dark.

“We transform that data so that we can actually see this huge range of details and reveal stuff that's near the dark end, which is where a lot of the cool stuff can be found,” Pagan said.

From there, Pagan uses photo editing software to layer images and assign colors to different features. Because JWST observes the universe in infrared—light beyond the spectrum that human eyes can see—Pagan uses a technique called chromatic ordering to assign colors based on the wavelengths of infrared light present. For instance, shorter wavelengths are assigned shades of blue, and longer ones appear in red hues.

Color can also be used to emphasize details or distinguish between physical features like space dust and swirling gases. Ultimately, Pagan said STScI’s goal for creating and sharing these images is to make astronomy accessible to a wider audience.

“I think it's important for people to understand that we present these images so that people can understand them,” she said. “Since they are infrared imagery, there has to be some level of interpretation, but we are basing it on science as best as possible.”

Participating in a project as “grand” as JWST—the world’s most powerful telescope—has been an exciting challenge for Pagan.

“Webb had been over 25 years in the making,” Pagan said. “The fact that it works and I get to put out an image showing what it sees—it’s powerful.”

While observations from JWST will continue to contribute to Pagan’s work, STScI is gearing up for its next big mission: NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, set to launch by May 2027. This telescope will be used to investigate exoplanets, dark matter and energy, and other mysteries of the universe.

Pagan and her team are already practicing with simulated data to understand the types of images that Roman will capture. Because of its ability to block starlight, Roman could offer an unprecedented look at exoplanets, planet-forming disks and other cosmic phenomena.

Whether it’s images of Neptune’s rings, Saturn’s moons or perhaps an undiscovered exoplanet in a distant corner of the cosmos, Pagan is excited to keep sharing her love of space with people around the world.

“One of my favorite parts of my job is seeing how much an image captivates people once it gets disseminated to the public,” Pagan said. “It’s so fun to be a part of that process of making astronomy engaging and to see people get excited about it.”