UMD Astrobiologist on Team Selected by NASA to Investigate Ocean Worlds and Their Organic Carbon Cycles

Ocean worlds such as Jupiter’s icy moon Europa and Saturn’s counterpart, Enceladus, could be among the most favorable places to discover life beyond Earth—and perhaps even a second, independent origin of life. With NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft scheduled to arrive at Europa in 2030 to determine whether its icy crust or under-ice ocean might be able to support life, NASA selected the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) to lead a five-year, approximately $5 million project that will combine a wide range of scientific disciplines to investigate ocean worlds in new, collaborative ways.

The Investigating Ocean Worlds (InvOW) project seeks to improve the analysis of data related to carbon-rich molecules that could be an indicator of biological activity and will be a focus of future life-detection missions.

“If you are alive today, this is the first generation where the question of whether there is life elsewhere in the universe could be answered in your lifetime,” said Chris German, WHOI senior scientist and InvOW principal investigator. “Previously, this was an abstract, intellectual, and philosophical question. We now know enough to say that it is entirely plausible that there is life out there, within humanity’s reach, and we just need to go and look.”

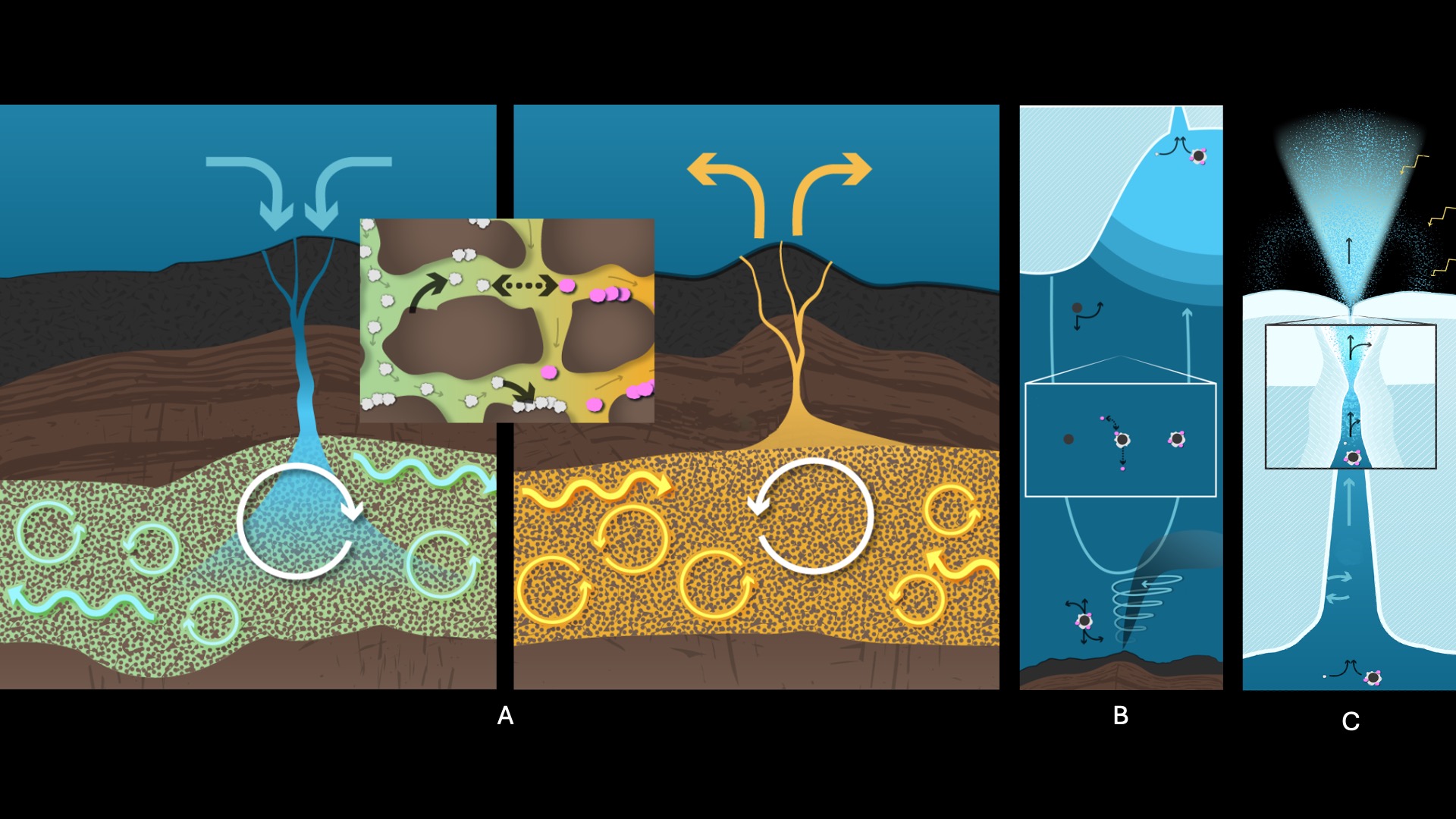

The InvOW project team spans 16 laboratories across the United States and will integrate a combination of disciplines (ocean, polar and space sciences) and use interdisciplinary approaches (theoretical modeling, laboratory experiments and fieldwork) to investigate three different domains on ocean worlds: the rocky subseafloor, the ocean itself and the icy outer shell, known as the cryosphere. A unifying focus will be to investigate how organic materials—potentially indicative of life—might be modified as they travel through Europa’s or any ocean world’s different domains before they reach a spacecraft’s detection system.

Marc Neveu, an associate research scientist in the University of Maryland’s Department of Astronomy and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, will co-lead the project’s investigation into how the chemistry of fluids and particles changes as they move through kilometers-thick ice shells and into space.

“I have helped NASA conceive future missions to search for life on ocean worlds, such as the Enceladus Orbilander, which rely on detecting and interpreting organic compound ‘signals’ from spacecraft, and I am excited that the InvOW project seeks to overcome some of the hurdles these missions face,” Neveu said. “InvOW will investigate ocean worlds that are rich in organic molecules that predate life and evaluate the transformations organic molecules undergo between where they are made in deep subsurface oceans and where they are detected by spacecraft.”

Neveu will conduct fieldwork, modeling and controlled laboratory experiments to evaluate chemical changes to organic compounds during their transition from ocean water to vapor and ice grains. He previously built a Simulator of Ocean World Cryovolcanism (SOWCr) that he and UMD geology Ph.D. student Mariam Naseem will use to simulate the process in a vacuum chamber.

On Earth, ocean life consumes so much of the organic carbon present, very little is left unconsumed. As a result, there is little to no “signal-to-noise” problem between detecting organic compounds that are the result of life against a background of non-biological material. In space, the opposite may be true. On other ocean worlds more distant from the sun, where there is significantly less energy to support biological activity, non-biological organic matter might dominate.

“On ocean worlds, identifying valid indicators of life might be a needle-in-a-haystack kind of problem,” German said. “Seeing through the background noise to be able to pick out signals that are definitively due to life will require rigorous examination. We need to rule out all of the other ways that signals could be generated, by non-life processes, so that they don’t otherwise confound mission scientists.”

The Investigating Ocean Worlds project builds on the NASA-funded Exploring Ocean Worlds (ExOW) initiative that German also led and that involved a number of the same scientists. While the earlier project focused on understanding physical and geological processes on ocean worlds, InvOW focuses on what German describes as the biggest problem to confront: making sense of any organic molecules detected from future ocean world missions, starting with the Europa Clipper.

Adapted from text provided by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.