Studying Dust in the Wind

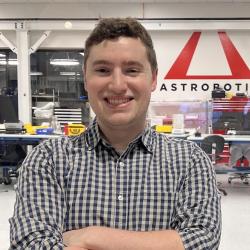

Astronomy Ph.D. student Serena Cronin explores space dust, galactic winds and other cosmic phenomena.

For University of Maryland astronomy Ph.D. student Serena Cronin, a dusty environment is not a dealbreaker—at least not when it comes to studying cosmic dust. These grains of solid material float in space or whip around galaxies while carried on high-speed winds.

“Some astronomers agree that dust is a nuisance because it can get in the way of astrophysical phenomena we want to study,” said Cronin (M.S. ’23, astronomy). “But there are also a lot of interesting things you can learn just by looking at dust."

Space dust offers clues about some of the biggest lingering mysteries in astronomy, including how galaxies evolve and generate stars and winds. Cronin tackles those questions and more as a researcher focused on galaxies beyond the Milky Way, including two that are relatively close to Earth: NGC 253 (an exceptionally bright and dusty galaxy) and Messier 82, or M82 (a starburst galaxy in the midst of rapidly birthing new stars).

“We study these two nearby galaxies because their proximity to us means we can look at them in exquisite detail,” Cronin said.

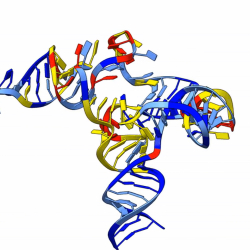

With Astronomy Professor Alberto Bolatto as her advisor, Cronin is contributing to ongoing studies of M82 using data captured by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). An April 2024 study that Bolatto led and Cronin co-authored showed M82’s glowing core and dust-speckled wind in unprecedented resolution—with a new image and paper on this topic expected soon.

“Alberto called me into his office when he first received the images, and I was immediately stunned at the complexity of the wind,” Cronin said last year when their paper was published. “Being one of the first people to lay eyes on these images reminded me of the sense of wonder and discovery that drew me toward this field in the first place.”

From space camp to college

As a child, Cronin loved flipping through her family’s National Geographic magazines. While there were plenty of pretty pictures, none impacted her as much as the ones from outer space.

“I was enamored with the Hubble Space Telescope images I saw,” she said. “I was not reading the articles because I was pretty young, but I remember staring at the images and taking them out and saving them.”

Cronin grew up in Cleveland, Ohio, and has fond memories of visiting the city’s Great Lakes Science Center, where she once attended a summer space camp and diligently took notes during lessons. Later, when the time came to enroll in college, studying astronomy felt like a no-brainer.

As an undergrad at the Ohio State University, she studied exploding stars and interned at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory. There, she used astrochemistry to understand the environment surrounding the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way. While she enjoyed that experience, she realized she would rather study the Milky Way indirectly.

“There's a lot we can learn from the Milky Way and those studies are important, but I like looking at galaxies that are different from ours or in different stages of their evolution,” Cronin said. “The main thing in my field that we're trying to understand is: How does a galaxy like the Milky Way get to where it is today?”

Galactic growth spurts

After earning her bachelor’s degree in 2020, Cronin moved on to UMD’s astronomy graduate program, drawn to its extragalactic research and proximity to national space institutes. Her research now focuses on starburst galaxies, some of which generate up to 100 solar masses, or sun-like stars, per year—far more than the Milky Way’s one or two new solar masses per year. This discrepancy is because starburst galaxies are in a different phase of their evolution, akin to experiencing a growth spurt.

“We think that the starburst stage is a pretty common evolutionary stage that occurred 10 billion years ago,” Cronin said. “We think a lot of galaxies go through it before eventually evolving into something like the Milky Way.”

In this way, studying other galaxies can offer insight into our own, Cronin explained. Her favorite starburst galaxy to study is M82, which grows stars about 10 times faster than the Milky Way. Such rapid star formation is “a pretty rare phenomenon in our local universe,” making it all the more interesting to researchers, Cronin said.

For the M82 paper published last year, Cronin played an integral role in separating space dust—a main component of galactic winds, which are partly spurred by star formation—from starlight, which complicates an image when added to the mix. She gained experience with astronomical image processing tools and learned new skills along the way.

“That was a side of astronomy I hadn't done before,” Cronin said, “and so I had to strengthen some coding skills to get it done.”

Once finished, Cronin was blown away by the final image, which revealed a “beautiful” galactic wind with detailed “bumps and wiggles” that couldn’t be seen in previous M82 images captured by Hubble. Having such a clear picture of galactic wind can help answer key questions in astronomy.

“A big question is how material moves throughout a galaxy, and one way that it can move is through these galactic winds,” Cronin said. “We want to understand how galactic winds transport gas and dust throughout a galaxy and out of it as well."

‘Next generation of science’

When she isn’t conducting or sharing research, Cronin loves going to UMD women’s basketball games, lifting weights at the Eppley Recreation Center and attending concerts. She also worked as a teaching assistant for an introductory astronomy course and mentored three students—one high schooler and two undergraduates—through UMD’s GRAD-MAP program.

Eager to share her knowledge with a wider audience, Cronin presented her research at an American Astronomical Society meeting and at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), where she met JWST flight operators and toured the mission control center.

“They’re mainly engineers, so they wanted to see the fruits of their labor,” Cronin said of her STScI audience. “Sharing this work has been very exciting.”

Now in the fourth year of her Ph.D. program, Cronin has two galactic studies about NGC 253 and M82 in the works and looks forward to sharing her findings. Looking back at her days of browsing National Geographic magazines, Cronin views her research with JWST data as a full-circle moment.

“It's cool because I started out looking at Hubble images and now I'm working on James Webb images, which is the next generation of science,” Cronin said. “I think ‘exciting’ is the best word to describe it, and I feel very lucky.”