Scientists Discover Volcanoes on Venus Are Still Active

New 3D model provides evidence that Venus is churning inside

A new study identified 37 recently active volcanic structures on Venus. The study provides some of the best evidence yet that Venus is still a geologically active planet. A research paper on the work, which was conducted by researchers at the University of Maryland and the Institute of Geophysics at ETH Zurich, Switzerland, was published in the journal Nature Geoscience on July 20, 2020.

“This is the first time we are able to point to specific structures and say ‘Look, this is not an ancient volcano but one that is active today, dormant perhaps, but not dead,’” said Laurent Montési, a professor of geology at UMD and co-author of the research paper. “This study significantly changes the view of Venus from a mostly inactive planet to one whose interior is still churning and can feed many active volcanoes.”

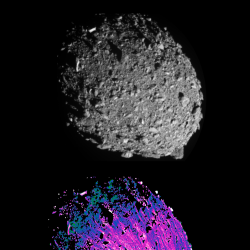

Scientists have known for some time that Venus has a younger surface than planets like Mars and Mercury, which have cold interiors. Evidence of a warm interior and geologic activity dots the surface of the planet in the form of ring-like structures known as coronae, which form when plumes of hot material deep inside the planet rise through the mantle layer and crust. This is similar to the way mantle plumes formed the volcanic Hawaiian Islands.

But it was thought that the coronae on Venus were probably signs of ancient activity, and that Venus had cooled enough to slow geological activity in the planet’s interior and harden the crust so much that any warm material from deep inside would not be able to puncture through. In addition, the exact processes by which mantle plumes formed coronae on Venus and the reasons for variation among coronae have been matters for debate.

In the new study, the researchers used numerical models of thermo-mechanic activity beneath the surface of Venus to create high-resolution, 3D simulations of coronae formation. Their simulations provide a more detailed view of the process than ever before.

The results helped Montési and his colleagues identify features that are present only in recently active coronae. The team was then able to match those features to those observed on the surface of Venus, revealing that some of the variation in coronae across the planet represents different stages of geological development. The study provides the first evidence that coronae on Venus are still evolving, indicating that the interior of the planet is still churning.

“The improved degree of realism in these models over previous studies makes it possible to identify several stages in corona evolution and define diagnostic geological features present only at currently active coronae,” Montési said. “We are able to tell that at least 37 coronae have been very recently active.”

The active coronae on Venus are clustered in a handful of locations, which suggests areas where the planet is most active, providing clues to the workings of the planet’s interior. These results may help identify target areas where geologic instruments should be placed on future missions to Venus, such as Europe’s EnVision that is scheduled to launch in 2032.

###

The research paper, “Corona structures driven by plume-lithosphere interactions and evidence for ongoing plume activity on Venus,” Anna J. P. Gülcher, Taras V. Gerya, Laurent G. J. Montési and Jessica Munch, was published on July 20, 2020, in the journal Nature Geoscience.

This study was supported by NASA (Award No. NNX14AG51G), the Swiss National Science Foundation (Award No. 200021_182069) and the EU project Subitop. The content of this article does not necessarily reflect the views of these organizations.

Writer: Kimbra Cutlip

Media Relations Contact: Abby Robinson, 301-405-5845, abbyr@umd.edu

University of Maryland

College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences

2300 Symons Hall

College Park, Md. 20742

www.cmns.umd.edu

@UMDscience

About the College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences

The College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences at the University of Maryland educates more than 9,000 future scientific leaders in its undergraduate and graduate programs each year. The college's 10 departments and more than a dozen interdisciplinary research centers foster scientific discovery with annual sponsored research funding exceeding $200 million.