From Scuba Diver to Auditory Neurocircuitry Researcher

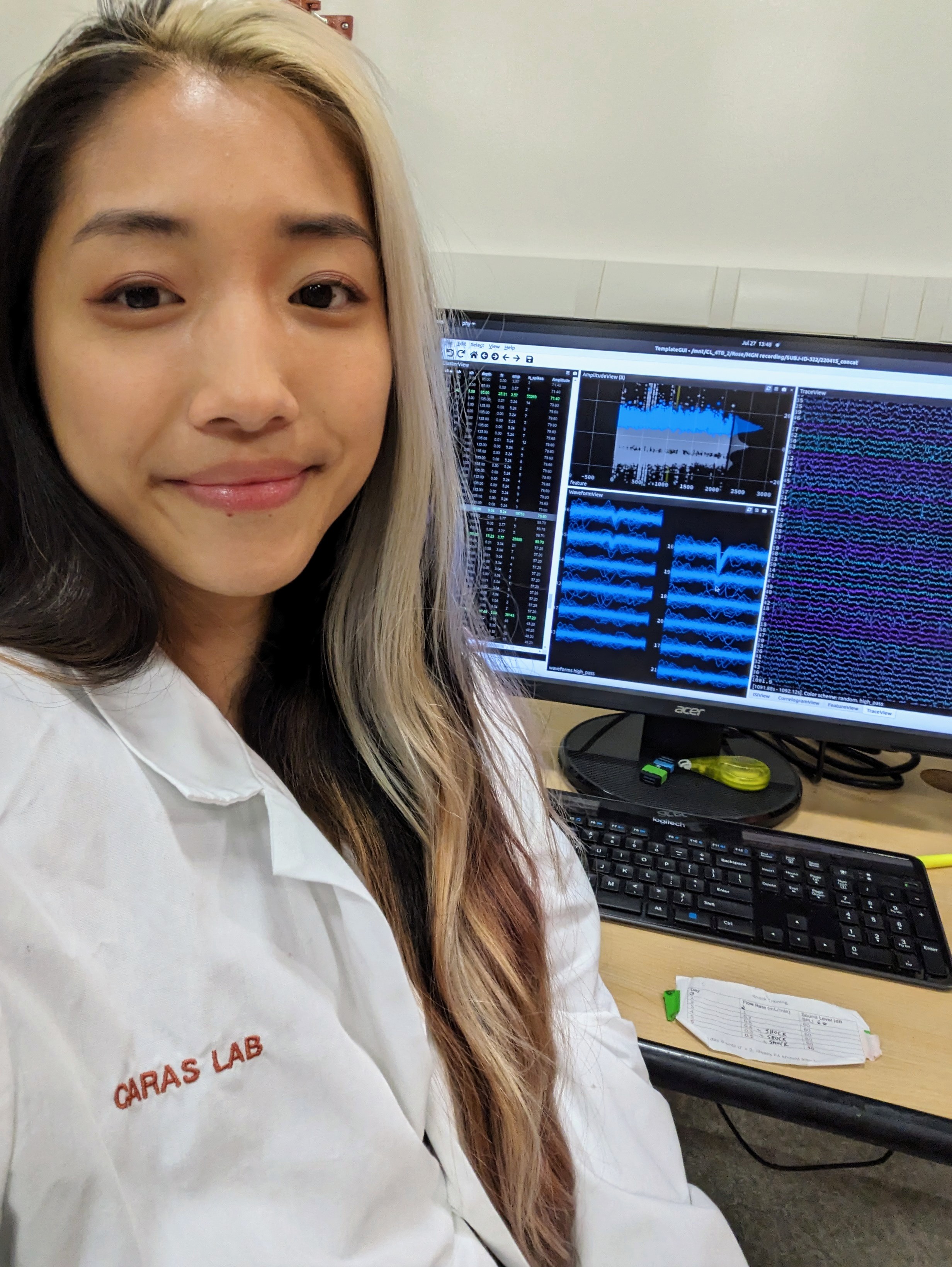

With an NIH graduate fellowship, Rose Ying continues to look for interesting ways to explore the unknown.

University of Maryland neuroscience and cognitive science (NACS) Ph.D. student Rose Ying always questions the world around her. She chases the answers to those questions with a more straightforward and hands-on approach than most, jumping right into the action.

When Ying developed a fascination for marine biology and coral reef ecology while studying biology at Wake Forest University, she trained in the Caribbean Island of Bonaire and acquired an international open water scuba diving license. Once she was an officially certified American Academy of Underwater Sciences research diver, Ying witnessed the interactions between native coral-inhabiting fish and invasive lionfish for herself.

After graduating in 2017, Ying briefly worked as a research technician at a University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill lab, where she learned about the field of neurocircuitry. She loved the idea of answering questions about the brain and how certain neural pathways facilitated learning.

When applying to graduate school, Ying came across UMD Biology Assistant Professor Melissa Caras’ work in the field. Intrigued by Caras’ research on the brain’s auditory system and its role in perceptual learning (improving the senses through practice), Ying decided to apply to UMD and its interdisciplinary NACS program, where she could truly combine her interests in biology and linguistics.

“I’ve always been interested in what allows us to learn languages, communicate and process natural sounds. Plus, I also happen to be bilingual,” Ying explained. “When I read about Melissa’s work, which goes into how the brain develops these skills for speech recognition and language acquisition, I thought that the opportunity to be part of it was a perfect match. So, I just went for it.”

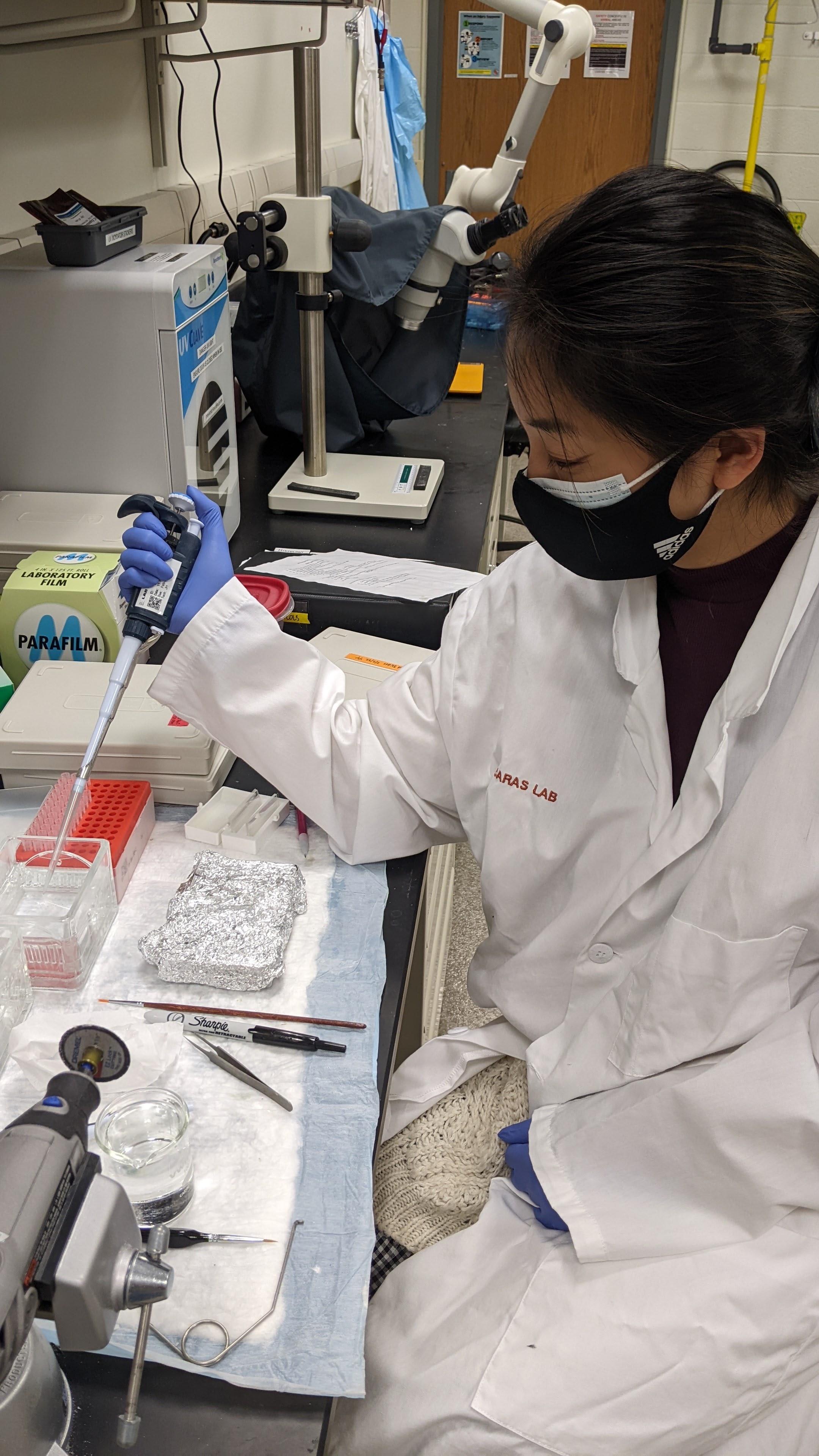

Now, with Caras as her faculty advisor, Ying works to uncover the biological mechanisms in the brain responsible for perceptual learning. The Caras Lab pursues this avenue of research by studying how animals can refine their sensory abilities to hear subtle differences between sounds that they couldn’t distinguish before. For her dissertation and an upcoming paper, Ying led the team in observing how or if animals reacted after listening to a range of sounds played to them and how behavior changed with each sound.

“Basically, we play a sound, and that sound tells an animal subject to do a specific action. In this study, we played an unmodulated sound that’s like white noise to tell the animal to drink water from a spout,” Ying explained. “When we played a different noise, an amplitude-modulated sound, the animal was supposed to move away from the spout. We gradually made this amplitude-modulated sound more similar to the unmodulated noise. This induces perceptual learning, where the animals learn to hear this stimulus that’s getting more and more difficult to detect. The goal of our experiment was to then record neural activity to see how neural changes might be correlated to this change in behavior.”

In April 2023, Ying was awarded a National Institutes of Health graduate fellowship to continue this research with guidance from Caras and Distinguished University Professor of Biology Catherine Carr.

As her mentor, Caras believes that the achievement is indicative of Ying’s growth in the Caras Lab and her potential in their research field.

“Rose is a phenomenal graduate student. She has the work ethic, creativity and grit to succeed in science,” Caras said “It’s been a delight mentoring her and I look forward to seeing where her career will take her next.”

Ying plans to use her award to investigate whether the brain’s subcortical regions impact the perceptual learning process.

“We know that the brain’s cortex impacts how we can improve our detection of low-saliency, hard-to-detect sounds, but it’s still a mystery what happens in the areas below the cortex, or the subcortical region,” Ying said. “There’s a feedback loop involved when it comes to learning, and we’re going to take a closer look at the neural activity in this area of the brain to see its role in the loop.”

Ying believes that the work she is doing in the Caras Lab today will eventually lead to breakthroughs in how medical professionals approach human brain health.

“If we figure out what brain pathways are used during perceptual learning, which is an important part of communication processes, maybe we can use that knowledge to improve or preserve sensitivity to sounds—especially in people who are aging or have a neurocognitive disorder,” Ying said. “Can we deactivate or stimulate these pathways to help people maintain important skills like language acquisition even after they’ve passed the critical period of language learning? Is it possible to restore these skills to people with sensory impairments? These are questions that I hope to contribute answers to.”