Researchers Measure the Light Emitted by a Sub-Neptune Planet’s Atmosphere for the First Time

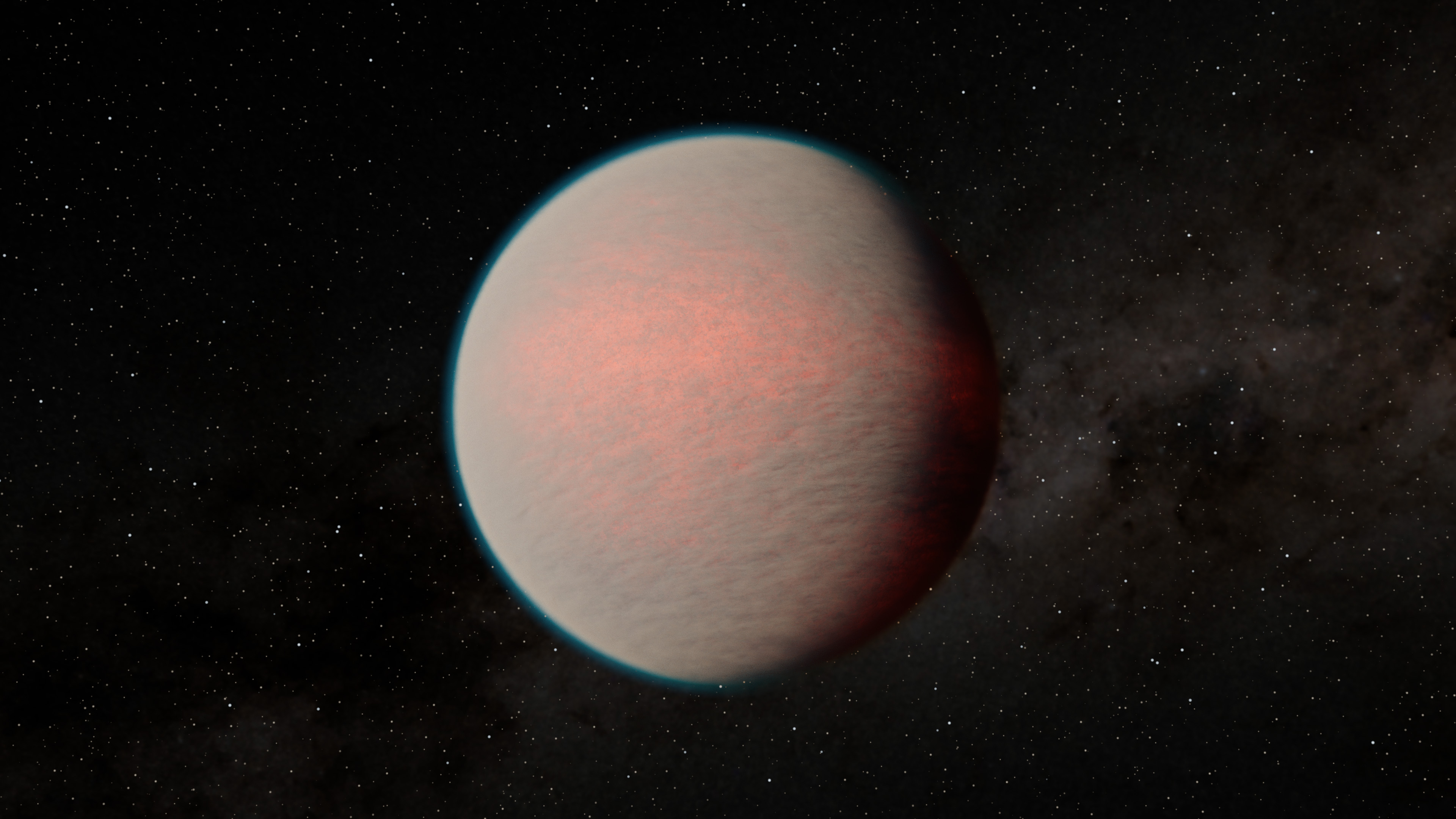

UMD astronomer Eliza Kempton says exoplanet GJ 1214b is too hot to be habitable but likely contains water vapor.

For more than a decade, astronomers have been trying to get a closer look at GJ 1214b, an exoplanet 40 light-years away from Earth. Their biggest obstacle is a thick layer of haze that blankets the planet, shielding it from the probing eyes of space telescopes and stymying efforts to study its atmosphere.

NASA’s new James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) solved that issue. The telescope’s infrared technology allows it to see planetary objects and features that were previously obscured by hazes, clouds or space dust, aiding astronomers in their search for habitable planets and early galaxies.

A team of researchers used JWST to observe GJ 1214b’s atmosphere by measuring the heat it emits while orbiting its host star. Their results, published in the journal Nature on May 10, 2023, represent the first time anyone has directly detected the light emitted by a sub-Neptune exoplanet—a category of planets that are larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune.

Though GJ 1214b is far too hot to be habitable, researchers discovered that its atmosphere likely contains water vapor—possibly even significant amounts—and is primarily composed of molecules heavier than hydrogen. University of Maryland Associate Professor of Astronomy Eliza Kempton, lead author of the Nature study, said their findings mark a turning point in the study of sub-Neptune planets like GJ 1214b.

“I’ve been on a quest to understand GJ 1214b for more than a decade,” Kempton said. “When we received the data for this Nature paper, we could see the light from the planet just disappear when it went behind its host star. That had never before been seen for this planet or for any other planet of its class, so JWST is really delivering on its promise.”

A ‘new light’

Sub-Neptunes are the most common type of planet in the Milky Way, though none exist in our solar system. Despite the murkiness of GJ 1214b’s atmosphere, Kempton and her co-authors determined the planet was still their best chance of observing a sub-Neptune’s atmosphere because of its bright but small host star.

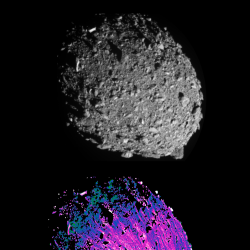

In their Nature paper, the researchers measured the infrared light that GJ 1214b emitted over the course of about 40 hours—the time it takes the planet to orbit its star. As day turns to night, the amount of heat that shifts from one side of a planet to the other depends largely on what its atmosphere is made of. Known as a phase curve observation, this research method opened a new window into the planet’s atmosphere.

“JWST operates at longer wavelengths of light than previous observatories, which gives us access to the heat emitted by the planet and allows us to create a map of the planet’s temperature,” Kempton said. “We finally got to see GJ 1214b in a new light."

By measuring the movement and fluctuation of heat, the researchers determined that GJ 1214b does not have an atmosphere dominated by hydrogen.

Potential water world?

The question of whether GJ 1214b contains water has long interested astronomers. Previous observations by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope suggested that GJ 1214b could be a water world—a loose term for any planet that contains a significant amount of water.

The latest JWST data revealed traces of water, methane or some mix of the two. These substances match a subtle absorption of light seen in the wavelength range observed by JWST. Further studies will be needed to determine the exact makeup of the planet’s atmosphere, but Kempton said the evidence remains consistent with the possibility of large amounts of water.

“GJ 1214b, based on our observations, could be a water world,” Kempton said. “We think we detect water vapor, but it’s challenging because water vapor absorption overlaps with methane absorption, so we can’t say 100% that we detected water vapor and not methane. However, we see this evidence on both hemispheres of the planet, which heightens our confidence that there really is water there.”

Reflecting on the findings

The researchers made another surprising discovery in their study: GJ 1214b is incredibly reflective. The planet was not as hot as expected, which tells researchers that something in the atmosphere is reflecting light.

Kempton said there is plenty of room for follow-up studies, including ones that take a closer look at the high-altitude aerosols that form the haze—or possibly clouds—in GJ 1214b’s atmosphere. Previously, researchers thought it might be a dark, soot-like substance that absorbs light. However, the discovery that the exoplanet is reflective raises new questions.

“Whatever is making up the hazes or clouds is not what we expected. It’s bright, it’s reflective and that’s confusing and surprising,” Kempton said. “This is going to point us toward a lot of further studies to try to understand what those hazes could be.”

###

In addition to Kempton, co-authors from UMD’s Department of Astronomy include Ph.D. students Jegug Ih and Arjun Savel, recent graduate Kenneth Arnold (B.S. ’22, physics and astronomy), postdoctoral associate Matthew Nixon and former postdoctoral associate Matej Malik.

Their study, “A reflective, metal-rich atmosphere for GJ 1214b from its JWST phase curve,” was published in the journal Nature on May 10, 2023.

This research was supported by NASA (Contract NAS 5-03127), the National Science Foundation (Award No. 1931736), the Heising-Simons Foundation, the John Fell Fund and the Canadian Space Agency. This story does not necessarily reflect the views of these organizations.