Researchers Discover Way to Predict Treatment Success for Parasitic Skin Disease

Findings from a new UMD-led study could help doctors select more effective treatments earlier for patients suffering from leishmaniasis, a disfiguring skin infection.

Nearly one million people worldwide are plagued annually by cutaneous leishmaniasis, a devastating skin infection caused by the Leishmania parasite. Predominantly affecting vulnerable populations in tropical and subtropical regions like North Africa and South America, this disease thrives in areas marked by malnutrition, poor housing and population displacement. Left untreated, it can lead to lifelong scars, debilitating disability and deep social stigma. Despite its global impact, there is no vaccine—and existing treatments are ineffective, toxic and difficult to administer.

A new study published in the journal Nature Communications on April 4, 2025, could transform how health care providers approach treating this disfiguring disease. A team of researchers from the University of Maryland and the Centro Internacional de Entrenamiento e Investigaciones Médicas (CIDEIM) in Colombia discovered a way to predict whether a patient suffering from cutaneous leishmaniasis will respond to the most common treatment, potentially saving patients from months of expensive, ineffective and toxic medication.

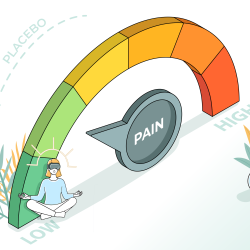

“It’s commonly said that the cure can be worse than the disease. This is very true with our current treatments of cutaneous leishmaniasis,” said Maria Adelaida Gomez, a microbiologist with CIDEIM and co-lead author of the study. “These drugs have a high toxicity profile, so patients may feel sick for weeks while being treated. There is no guarantee that the treatment will be effective, so patients may stop treatment or visit another doctor to repeat the process. And even if they are cured, they’re likely to have a scar forever. This is the reality of leishmaniasis in Colombia and many other countries around the world.”

UMD Professor of Cell Biology and Molecular Genetics Najib El-Sayed, co-lead author of the study, noted that the standard drug used to treat the disease—meglumine antimoniate—typically fails in about 40-70% of patients it is administered to.

“This failure rate holds even when patients complete the full course of the treatment, which takes up to 14 weeks,” El-Sayed said. “Finding out how effective the medication will be on a patient early on is very important because it can prevent weeks or months of ineffective treatment and help patients access more suitable alternatives much sooner.”

The team found that patients who failed to respond to meglumine antimoniate showed a distinctive pattern in their immune system, a sustained inflammatory state called a type I interferon response. This response is usually a crucial part of the body’s early response system against viruses, helping cells detect a pathogen and recruiting resources to fight against it.

“While this response is essential for fighting some infections, we found that when it remains elevated for too long, it can interfere with the treatment and healing process in patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis,” El-Sayed explained. “This elevated type I interferon response was observed across several innate immune cell types we analyzed in patient blood samples. By tracking these changes throughout the treatment process, we identified a clear pattern that distinguishes patients who successfully recover from those who won’t respond to standard medication.”

The researchers also developed a sophisticated scoring system that can accurately predict treatment outcomes for newly diagnosed patients using advanced machine learning techniques. By analyzing the activity of just nine genes, they could predict whether the treatment would work on a cutaneous leishmaniasis patient with 90% accuracy.

“This is significant progress for health care providers and scientists working to improve outcomes for cutaneous leishmaniasis patients,” Gomez said. “The disease is starting to move to new places such as the United States, which means we need these resources more than ever.”

While the current test requires sophisticated laboratory equipment, the team is already working to produce a more portable and user-friendly version of the technology for doctors to use in the field. The researchers hope their new findings, particularly regarding the type I interferon pathway, could be a promising avenue for developing new therapeutics for cutaneous leishmaniasis. Their conclusions represent a shift from more traditional approaches —which usually focus solely on eliminating the parasite—to treatment methods that also consider the patient’s natural immune responses.

“It’s really one of the first attempts to translate laboratory findings of this disease into practical applications,” El-Sayed said. “Understanding why some patients don’t respond to treatment has been a major challenge in managing this disease. This work opens the door to precision medicine and developing better strategies that can personalize treatment for a wide range of patients.”

###

The paper, “Innate biosignature of treatment failure in human cutaneous leishmaniasis,” was published in Nature Communications on April 4, 2025.