Research at the Frozen End of the Earth

With snow swirling and visibility falling, University of Maryland geology researchers put their faith in their pilots and mountaineers as they flew over the Ross Ice Shelf, a massive, floating, frozen sheet off the edge of Antarctica.

The mission: To deploy and retrieve valuable scientific equipment without being swallowed by one of the many crevasses hidden beneath the snowdrifts, which can cause humans—and even planes—to vanish without a trace.

Through a combination of in-the-air technology, with radar scanning for cracks, and on-the-ice testing—a low-tech, long pole to tap for weak spots—the skilled support staff of McMurdo Station made sure Associate Professor Nick Schmerr, Assistant Professor Mong-Han Huang and doctoral student Kathrine Udell Lopez were able to safely collect data that couldn’t be acquired anywhere else on the planet.

“It’s super exciting,” said Schmerr, who hoped to make the trip for eight years. “We’ve been waiting a long time to get down there. There’s been a series of roadblocks, with government shutdowns, then the global pandemic.”

He and scientist Terry Hurford, of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, kicked off the first part of the expedition, spending three weeks in November and December at McMurdo Station, the largest U.S. research facility in Antarctica, to place instruments along a large rift on the ice shelf.

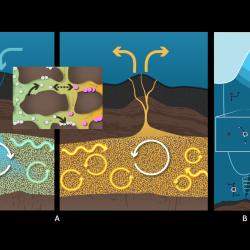

That work is part of Schmerr’s ongoing research on icy satellites, such as Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus, which both have subsurface oceans that could hold clues to the origins of life in the solar system. Science has been limited so far to satellite-based explorations of those moons, so Schmerr’s research in Antarctica is an earthly analog for actually being there. Developing a deeper understanding of these geological processes can also add to climate change data, as ice shelves melt and affect sea level rise.

“A totally alien, gorgeous landscape”

It’s not easy to get to McMurdo. It’s a 24-hour journey, with two layovers, from Washington, D.C., to Christchurch, New Zealand, where all personnel have to wait for ideal weather conditions before making the last leg of their trip. In Schmerr’s case, a COVID outbreak at the station put a pause on incoming flights, throwing another wrench in his plans. When he finally got the all-clear to go, it was aboard a military cargo plane. “They’re not the world’s best accommodations,” he joked about the loud, cold ride.

Upon arrival, the team conferred with the pilots and mountaineers who support McMurdo researchers about the best way to deploy equipment onto the ice shelf, about a 90-minute flight on a small Twin Otter airplane from the station.

An ice shelf is “this big flat sheet of ice that is essentially featureless,” Schmerr said. The Ross is about 1,000 feet thick and the largest in the world, a little smaller than Texas. “It’s a totally alien, gorgeous landscape. There is white in all directions, and when you fly up to these rifts, that’s the first real topography you see. It’s really exciting—a giant crack cutting through the ice. Everyone on the plane was glued to the windows.”

The plane is equipped with skis to land on the ice, and a mountaineer exits the plane first to manually ensure safety because even “smaller crevasses could swallow a person,” Schmerr said. Though it’s Antarctic summer, windchills can still drive temperatures down to the single digits, so he had to layer up with the famous “Big Red,” a heavily insulated coat issued to all scientists and staff at McMurdo.

Once on the shelf, he and his team had about 20 minutes at each location to place their GPS and seismometers in order to measure how tides cause fractures in the ice. Originally, they were prepared to cross-country ski and drag their equipment—which weighs hundreds of pounds—behind them on sleds across the ice. Luckily, they found the shelf surface reasonably smooth enough for the plane to taxi from spot to spot, enabling Schmerr’s team to set up 20 stations spanning about 10 kilometers on each side of the rift within four days.

“You put them out, turn them on, and then walk away for a month and hope everything worked!” he said.

In mid-January, Huang and Udell Lopez made a separate trip to retrieve the equipment. (“She really won the lottery there for a first hardcore field experience!” said Schmerr of Udell Lopez.)

For almost a week, they were at the mercy of the weather gods, getting ready before 7 a.m. each day only to be told they wouldn’t fly out to the ice shelf. When they finally got the literal all-clear, they had to scramble to collect all the instruments in just one day—enlisting the pilots and mountaineer to unscrew solar panels and organize equipment—since they couldn’t count on another flight.

Seals and Whales and Sea Urchins, Oh My

From plunging their hands into icy waters to hold sea spiders to hiking out onto the sea ice to see fat Weddell seals and their newborn pups, both teams got a chance to explore McMurdo’s environs—in 24-hour daylight due to their proximity to the South Pole—before heading back.

“We got the opportunity to see how sea ice gradually breaks into little pieces and then goes into the water. Once there is more surface water, more seals, skua (sea birds) and whales appear on the sea surface,” said Huang. Schmerr also visited a lab with a touch tank, where he braved icy water to pick up sea urchins and other local wildlife.

One of the biggest challenges, however, was feeling disconnected. “You have to wait for a computer station to check your email, at 1990s-era dial-up speed. It’s painful for anyone used to modern technology,” Schmerr said. “You’re cut off from the rest of the world.”

Day-to-day life at the station, despite being at the end of the Earth, would be very recognizable to UMD students. They lived in a shared room with plenty of roommates, walked to a cafeteria each day for meals, and had they stayed longer, could even have joined a variety of clubs for interests like crafting or running. “There’s even a disc golf course out there,” Schmerr said.

Written by Karen Shih

Photos courtesy of Terry Hurford, Nick Schmerr and Mong-Han Huang