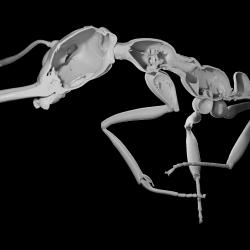

New Study Shows Island Ant Communities in Sharp Decline

UMD entomologist Evan Economo’s novel approach to studying ant populations revealed signs of decline in 79% of species found only in Fiji.

Insects are a crucial component of healthy ecosystems, but around the world, entomologists warn of an impending insect apocalypse if populations continue to plummet.

New research from scientists at the University of Maryland, the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST), and their collaborators identified an alarming example of this trend in Fiji, an archipelago with more than 300 islands in the South Pacific. Their study, published in the journal Science on September 11, 2025, uncovered a decline in 79% of Fiji’s endemic ant species—native insects found nowhere else on Earth.

The researchers correlated the arrival of humans with the steepest ant declines seen in the last few hundred years—a period marked by European contact, colonization, global trade and the introduction of modern agricultural techniques.

Though the researchers cannot pinpoint the exact cause of these declines, one of the study’s senior authors, UMD Entomology Professor Evan Economo, said the clues point to human effects. Ant population changes have consequences for Fiji’s ecosystem and could also serve as a warning for endemic insects in other parts of the world.

“Fiji has some of the most spectacular and geographically restricted ant species on Earth,” said Economo, who also holds the James B. Gahan and Margaret H. Gahan Professorship at UMD and an adjunct professorship with OIST. “The fact that the endemic species are declining is of huge concern—both for the future of these species in Fiji and for the possibility that it is a much more widespread phenomenon affecting other types of insects and on other islands.”

Reconstructing the history of Fiji’s ants

Like most places in the world, there has been no historical monitoring of how Fijian insect species have changed over long periods of time. To infer trends, the research team relied on ant samples from museum collections. By studying the ants’ genomes and tracing their evolutionary relationships, the researchers were able to determine when different species arrived on the islands and how their populations have changed in recent times.

“It can be difficult to estimate historical changes to insect populations, because with few exceptions, we haven’t been directly monitoring populations over time,” Economo said. “We take a novel approach to this problem by analyzing the genomes of many species in parallel from museum specimens collected recently. The genomes hold evidence of whether populations are growing or shrinking, allowing us to reconstruct community-wide changes.”

One of the challenges of using museum collections for this type of research is that DNA degrades over time. To avoid this issue, the researchers used special sequencing methods known as museumomics to compare small fragments of DNA.

The team sequenced the genomes of thousands of ant specimens from more than 100 different species and identified 65 instances of new ant species arriving on the islands, which are known as colonization events. These events ranged from natural colonization with no human involvement millions of years ago to species introduced by humans after Fiji became part of global trade networks.

Building on this history, the researchers used population genetics models to infer trends across the Fijian archipelago. While most of the islands’ endemic species declined, Fiji saw dramatic increases in the populations of non-native ant species in recent years.

“On islands, non-native ant species are a major problem, disrupting local ecosystems, driving native species of all kinds toward extinction and causing problems for human health and agriculture,” Economo said. “It is likely that the rise of non-native ant species is part of why the endemic species are declining as a group, along with other pressures.”

Economo noted that the small number of endemic ant species that are not experiencing declines tend to be the most tolerant of disturbed habitats, such as urbanized or agricultural lands.

‘Canary in the coal mine’

Beyond Fiji, these findings could provide a window into the health of insect populations on a larger scale. Islands are biodiversity hot spots and, in some cases, serve as microcosms of global trends.

“Being closed, isolated ecosystems, islands are expected to feel the effects of human impact faster, so they are kind of a canary in the coal mine,” said the paper’s first author, Cong Liu of the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology.

In the future, the team hopes their research will continue to inform the scientific community’s understanding of insect populations. Determining whether recent observations are part of longer trends can help advise conservation efforts and identify factors contributing to the global insect apocalypse.

At UMD, Economo plans to keep gleaning new information from the molecular data hidden within museum samples. He noted that the nearby Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History has the largest insect collections in the world, and he hopes to establish collaborations that continue to shed light on globally important insect species.

“Insects are essential for the environment,” Economo said. “As scientists, we need to play our part in their protection, and provide and analyze the relevant data to ensure the long-term integrity of our ecosystems.”

###

The paper, “Genomic signatures indicate biodiversity loss in an endemic island ant fauna,” was published in the journal Science on September 11, 2025.

This article was adapted from text provided by the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology.

This research was supported by subsidy funding to OIST and by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Grant Nos. 17K15180, 18K14768 and 16J00372). This article does not necessarily reflect the views of these organizations.