Bringing Salmon Back

As CEO of the nonprofit Long Live the Kings, Jacques White (Ph.D. ’91, marine estuarine environmental sciences) works to save wild salmon in the Pacific Northwest.

Jacques White grew up across the street from Puget Sound, an estuary in the state of Washington that, in White’s words, “kind of looks like an upside-down Chesapeake Bay on a map.”

Surrounded by nature’s bounty, White’s family turned to local waters for food and fun.

“I spent much of my time on the shoreline or docks of Puget Sound fishing, catching crabs, digging clams, opening oysters and eating them right on the beach,” said White (Ph.D. ’91, marine estuarine environmental sciences). “It used to be common to get in a rowboat just offshore of Seattle and catch large salmon for dinner.”

By the time White left Washington in the early 1980s to study marine science in Louisiana and eventually Maryland, salmon populations started succumbing to a century’s worth of compounding threats.

“In western Washington 120 years ago, salmon and trees were the main products. We didn’t have the software industry, we didn't make jets and we didn’t sell coffee,” White said. “Salmon were a little more replenishable than forests, but it didn’t take long for major salmon stocks in the Columbia River and in Puget Sound to be significantly depleted by industrial fishing.”

Today in state waters, 14 populations of salmon and steelhead—a type of trout that behaves like a salmon—are listed as threatened or endangered.

White, who felt compelled to return to his home state after more than a decade away, has made it his mission to restore salmon—and sustainable salmon fishing—to Washington’s waters. He is CEO of a Seattle-based nonprofit called Long Live the Kings (LLTK), which aims to remove barriers that salmon face on their arduous journey from streams to sea and back again. Having studied coastal issues for decades, White remains convinced that the organization’s goal is achievable.

“I’m one of those people whose cup is always a quarter full. I’m just optimistic by nature,” White said. “But we are also standing on the shoulders of really good scientists who have collected information on salmon for decades. We have the tools to understand what’s going on with salmon from trees to seas, as we like to say.”

A tricoastal career

Despite White’s early introduction to the sea, he didn’t consider a career in marine science until he took classes on the subject as an undergrad at the University of Washington.

“I don’t think I knew I wanted to be an oceanographer, although I was quite fond of Jacques Cousteau—maybe because he has the same name as me,” White said with a laugh. “I went through a progression of potential career paths and about halfway through undergrad chose oceanography and had no regrets.”

After earning a bachelor’s degree in oceanography and zoology in 1982, White earned a master’s degree in marine science in 1985 from Louisiana State University. Shortly thereafter, he started exploring Ph.D. programs and took an interest in the plankton research being conducted by Michael Roman at the University of Maryland. He applied and ultimately enrolled at UMD, where he worked with faculty who demonstrated “a social conscience and commitment to the highest academic principles.”

“What I did when I was a graduate student at the University of Maryland was invaluable to my intellectual and professional development. It gave me more confidence and more appetite for risk,” White said. “I learned a ton and was given a lot of freedom to be as creative as I could be, and that led to some opportunities beyond my graduate education.”

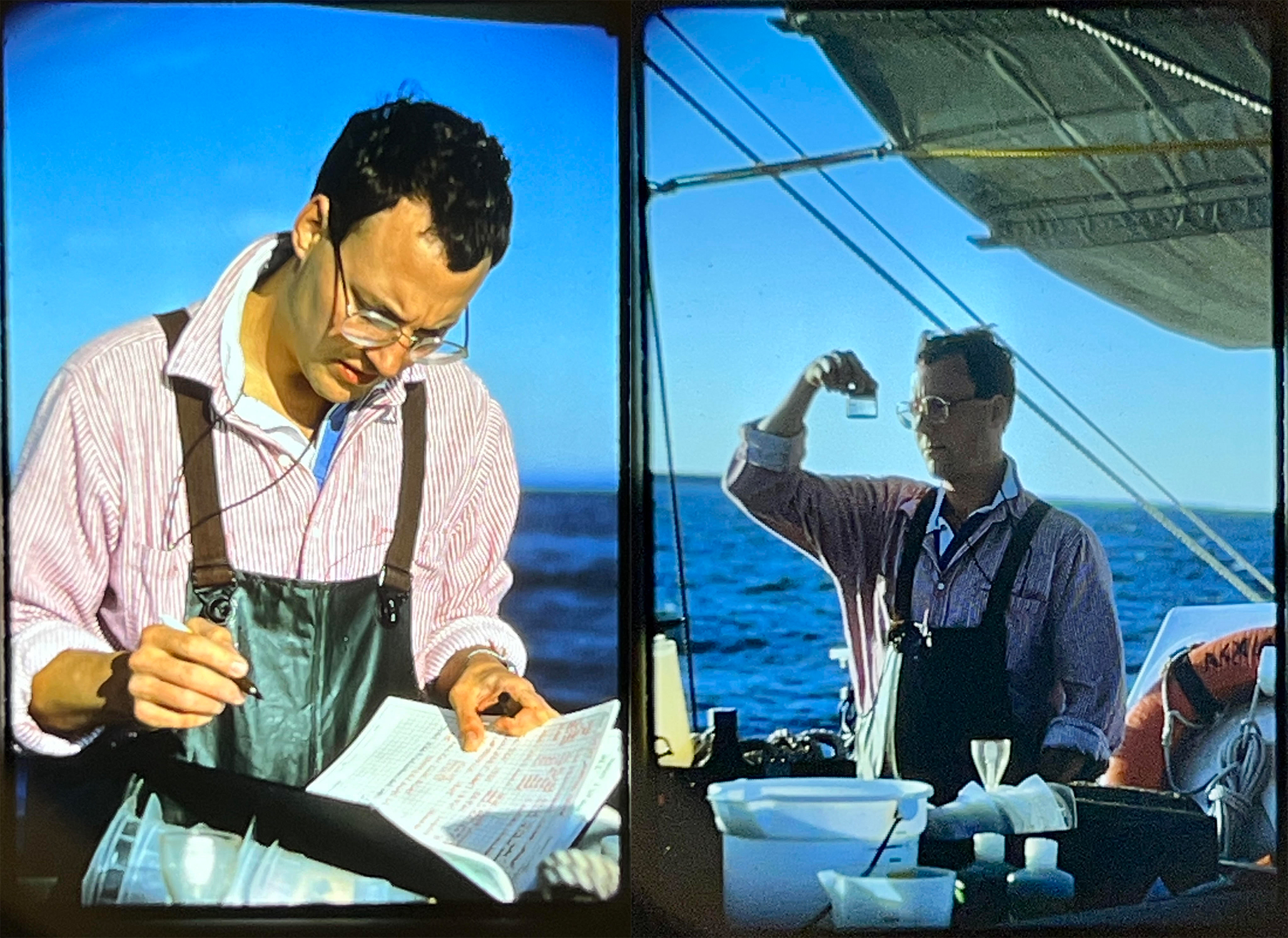

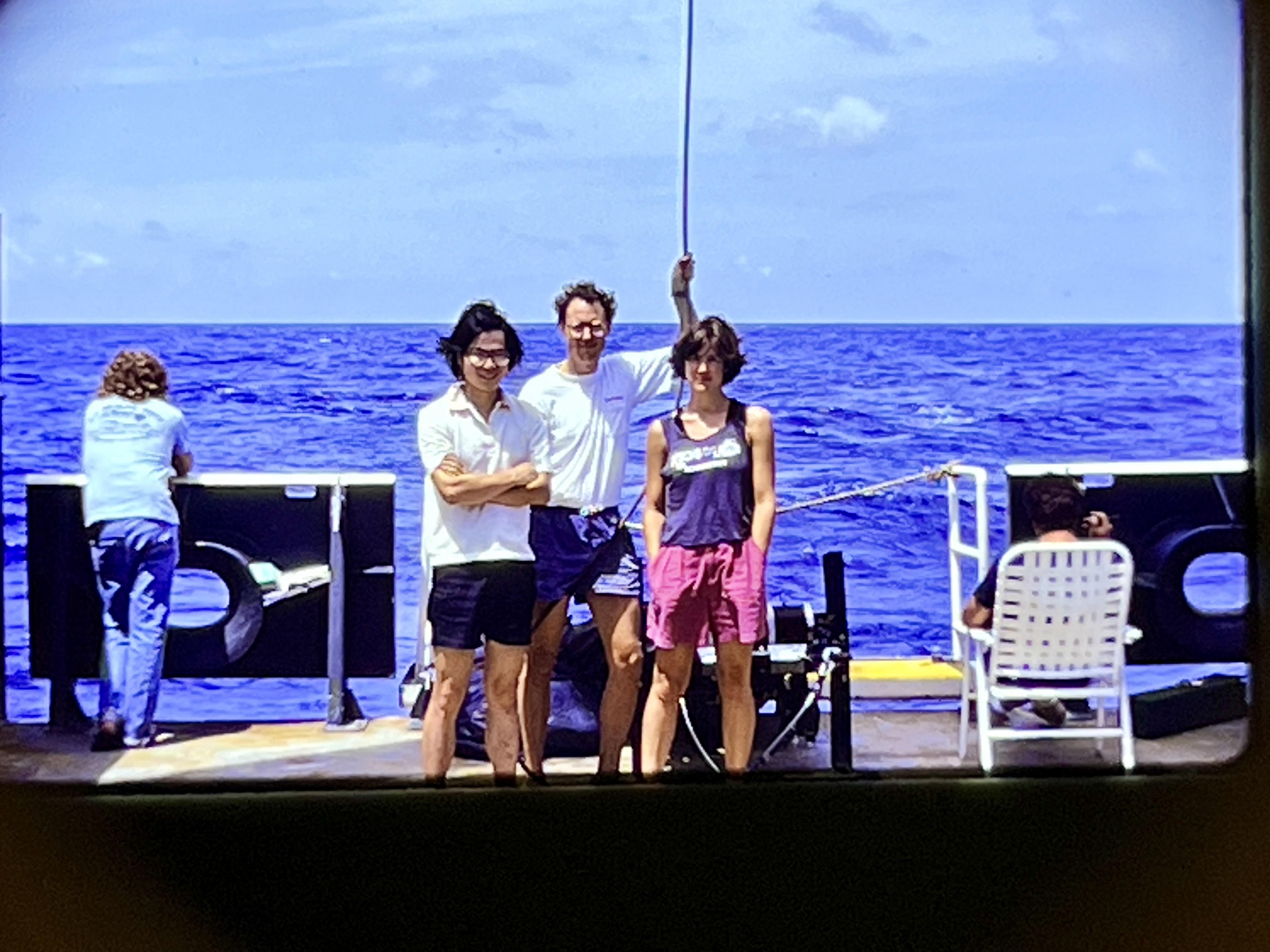

For White, those opportunities included a postdoc at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science’s Horn Point Laboratory—where he studied sea nettles, a stinging jellyfish that he calls the “bane of the Chesapeake Bay”—and a postdoctoral fellowship at the Smithsonian Institution, where he assessed the relationship between zooplankton and oxygen concentrations. Through UMD, White also joined an international research program called the Joint Global Ocean Flux Study to better understand the ocean’s carbon cycle.

“I got to spend a good part of 1992 on a ship in the Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and Tahiti, and that was super fascinating,” he recalled. “From that, I developed a relationship with a professor at the University of Delaware and became a junior research scientist there.”

In Delaware, White continued to study carbon fluxes in coastal waters, sparking an even deeper interest in the changes the ocean was undergoing—not just locally, but globally.

“I started to become concerned about climate change and environmental issues and wanted to explore other pathways other than academic research for a career,” he said.

When White received an offer to work on conservation issues in his home state, he jumped at the chance. He moved back to Washington in 1995 and spent the next eight years working for a small nonprofit called People For Puget Sound, followed by seven years with The Nature Conservancy as the global nonprofit’s director of marine conservation in Washington.

In the latter role, White created a marine conservation program in Washington from scratch and helped raise over $10 million for the protection and restoration of Puget Sound shorelines.

“After 15 years of being a project and program manager, I wanted to try a different challenge,” White said. “The executive director job at Long Live the Kings became available, so I applied and got it. Since 2010, I have been focused on salmon recovery here in the Pacific Northwest.”

‘On a mission’

Long Live the Kings aims to restore salmon—including the smaller coho species and the larger Chinook species known as “king salmon”—as well as steelhead and other local fish. The organization does so by removing the barriers that fish face, whether it’s advocating for safer fish passages and habitat restoration, removing tire dust and harmful chemicals from stormwater runoff, or rearing steelhead and Chinook in more controlled environments until they are ready to be released into the wild.

The organization’s goal is to provide enough fish for Indigenous peoples in Washington—who have a legal right to half of all harvestable fish in local waters—as well as non-tribal fishers and endangered southern resident killer whales that rely on salmon for food.

“For those of us who work on salmon issues, developing meaningful partnerships and supporting tribal interests is critically important,” White explained. “Tribes see salmon not only as an economic engine for their communities but also as a deeply held part of their culture.”

In December, Long Live the Kings co-hosted an international salmon and climate workshop, with Indigenous and First Nations groups comprising more than a quarter of the attendees. The meeting was part of a larger initiative to understand and address the climate crisis that salmon are facing.

With waters becoming increasingly warm, food webs are being thrown off balance, affecting the availability of the plankton and small forage fish that salmon feed on. White said salmon advocates will need to design “creative” solutions that take the rapidly changing habitat into account.

Despite the many challenges, White remains optimistic that salmon populations can be recovered. He serves on his local Puget Sound Salmon Recovery Council and the international North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission, and he puts stock in the environmental stewards who are putting in the work each day.

“I see hope, and I think part of my hope is tied to the commitment I see on the part of tribes and First Nations on the West Coast,” White said. “They have a ‘seven-generation view,’ so they’re thinking, ‘What do we have to do to make sure that our grandchildren’s grandchildren’s grandchildren have access to this resource?’ I think that is the kind of perspective that we need to have.”

White also draws inspiration from the very animals he has sworn to protect. Salmon, even in the face of adversity, are wired to keep moving forward.

“I think I like salmon because they’re so persistent—particularly when they come back to freshwater to spawn,” White said. “They’re on a mission and you can’t stop them.”