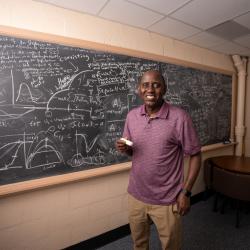

Biology Professor Joshua Weitz Answers Questions About Pandemic Prevention

The College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences hosted a Reddit Ask-Me-Anything ahead of the release of his new book on the future of pandemics.

University of Maryland Biology Professor Joshua Weitz participated in an Ask-Me-Anything (AMA) user-led discussion on Reddit to answer questions about epidemic modeling and pandemic prevention.

Weitz directs an interdisciplinary group focusing on understanding how viruses transform the fate of cells, populations and ecosystems and is the author of the textbook "Quantitative Biosciences: Dynamics across Cells, Organisms, and Populations." At UMD, Weitz holds affiliate appointments in the Department of Physics and the Institute for Advanced Computing and is a faculty member of the University of Maryland Institute for Health Computing.

Weitz’s new book, “Asymptomatic: The Silent Spread of COVID-19 and the Future of Pandemics" was published by Hopkins University Press on October 22, 2024.

Postdoctoral researchers Stephen Beckett and Mallory Harris joined Weitz to answer questions on Reddit.

This Reddit AMA has been edited for length and clarity.

What are some pathogens you think are candidates for the next pandemic, and what if anything can be done to reduce their risk?

(Weitz) There are many viruses lurking in zoonotic reservoirs. Increasing land use, mobility, and climate change all mean that the emergence or transfer of a virus from a human-animal interaction could inadvertently lead to illness or worse—human-to-human transmission and spread. Our group tends to worry primarily about respiratory viruses (e.g., coronaviruses and influenza), but there are many other classes of viruses to worry about, including pox viruses, flaviviruses (the causative agents of Dengue, Zika, West Nile disease and more), and filoviridae (the causative agents of Ebola and Marburg). In doing so, one also has to be mindful that pathogens of pandemic potential may not necessarily cause as much harm to individuals, and nonetheless cause far more severe outcomes to populations as a whole.

The story of coronaviruses provides important lessons. There have been three major coronavirus outbreaks in the past two decades, first SARS-1, then MERS, and finally SARS-CoV-2. Both SARS-1 and MERS caused significantly higher mortality per individual infection than SARS-CoV-2. But SARS-CoV-2 ended up leading to the deaths of at least 7M individuals globally and more than 1M individuals in the US alone. The challenge was the SARS-CoV-2 ended up generating about as many asymptomatic/mild infections as symptomatic infections—these asymptomatically infected individuals (including those who had not yet developed symptoms) could still transmit onwards to others who could end up with a severe infection. This is a key theme of ‘Asymptomatic’ (forthcoming this month from JHU Press). Hence, our barometer for what makes a pathogen a threat to global health must go beyond metrics of individual harm to include assessment of detection and controllability. We should be investing in efforts to develop vaccines, information sharing, and response tools that can help identify signatures of respiratory disease outbreaks of pandemic potential, develop and deploy effective response strategies, and minimize pandemic impacts.

What is quantitative biology?

(Weitz) Quantitative biology integrates mathematical theories and computational models as essential tools of inquiry to understand how living systems work across scales from cells to organisms to populations to ecosystems. Historically, training in the life sciences has prioritized experimental and/or observational studies with minimal requirements in mathematics, statistics and computing. Hence, it might appear that ‘virtually all of biology research uses math in some way,’ but in practice, many experimental labs do analyze data quantitatively but do not necessarily integrate mathematical and computational models as a core part of their approach to understand the natural world. That is changing. There are now multiple ‘Quantitative Biology/Biosciences’ style conferences, summer schools, and graduate programs that combine best practices for mathematical, physics, and computational training in classroom settings with the laboratory-centered training approach in many life sciences programs. Students who are interested might want to check out my new textbook ‘Quantitative Biosciences: Dynamics Across Cells, Organisms and Populations’ (nearly a decade in development), along with accompanying computational companions in R, Python, and MATLAB written with student co-authors, available via Princeton University Press - https://bit.ly/qbios_book_amazon.

We have regulations and infrastructure to stop people from getting sick from food and water. Do you think it's time we took a similar approach to getting sick from the air (i.e. air filtration standards for indoor public places)?

(Beckett) Yes. While it took time for the airborne and asymptomatic transmission of COVID-19 to be widely recognized, guidance towards masking and meeting outside or in well-ventilated conditions was part of public health guidance since the early onset of the pandemic. Technologies such as masking and Corsi-Rosenthal boxes are relatively low cost and easily implemented in multiple settings by individuals, though both faced uncertainty (provoking controversy) regarding efficacy in their initial deployment. Some building codes do incorporate air filtration standards, and I think there is wider recognition of the benefits of indoor air quality more generally.

Going forward, possible mitigation efforts could include retrofitting air filtration into older buildings, utilizing air quality indicator measurements (such as via CO2 monitors), and considering newer technologies such as germicidal UV. Finding effective strategies and effectively communicating them to the public is of broad interest. This essay by Dr. Joseph Allen (Harvard School of Public Health) may be of service in framing the broad set of issues, including the importance of ASHRAE ventilation standards

How does the scientific community evaluate the credibility of different models of the spread of epidemic diseases?

(Harris) There have been a few efforts to compare the performance of different models after the fact and see what we learn. For example, the CDC has an annual FluSight forecasting challenge for influenza, and there have been efforts to revisit models developed by different institutions participating in the COVID-19 Scenario Modeling Hub (now expanded to focus on flu and RSV as well). As outbreaks are happening, the modeling community is constantly testing and critiquing each other’s models and the assumptions encoded in them. I was part of an early COVID modeling effort, and we went back and assessed our model’s near-term predicting performance over time and wrote about some of our bigger takeaways about challenges to modeling at the beginning of an outbreak.

(Weitz) As Mallory noted, there have been efforts to run synthetic experiments after an epidemic as a means to improve infrastructure and take away key lessons. A major effort took place after the Ebola Virus Disease outbreak in 2014-16. But, each pandemic is unique. Hence, the experience of responding to COVID-19 was challenged by the speed, size, and complexity of impact. In response, epidemic modeling teams had to adjust models and develop infrastructure (including data infrastructure) at the same time as the disease was spreading globally. Alessandro Vespignani likened this to modeling in a ‘war.’ To extend this analogy, we should absolutely try in ‘peacetime’ to build better infrastructure for epidemic response.

Looking back at early 2020 also teaches us that institutional reputations for modeling capabilities are not always consistent with their technical capabilities. This can lead to perception gaps and misalignment of political response. In my book, I discuss the Institute for Health Metric and Evaluation (IHME) and its role in early 2020 in advancing a narrative that COVID-19 was about to disappear nearly as soon as it began. Despite doing excellent work in other sectors of health policy response, the IHME made a series of mistakes, including using a curve-fitting approach rather than a mechanistic modeling approach to project case counts forward. This led to erroneous projections of 0 cases by Summer 2020 despite significant evidence that the vast majority of the globe was immunologically naive and susceptible to infection. Members of the epidemic modeling community tried to argue against this narrative. Eventually, the IHME shifted its approach. But, this does point to a need to have genuinely open conversations about assumptions built into models and to hold models up to scrutiny. Yes, they can and should adapt. Precisely so, it is important that models and data are shared so that policymakers and the public understand the assumptions driving major, socioeconomic and health policy decisions. We must also accept the fact that pandemic science is still evolving – and despite the ability to make long-term forecasts it is worth asking ourselves the question: should we?

(Beckett) There are ongoing challenges here – especially as human behavior can influence future disease transmission. In doing so, the window for prediction of how an epidemic will advance is limited – meaning that one may not expect the situation today to reflect the situation a month from now. Models must respond to the evolving context of an infectious disease, whether that is changes in mobility, interventions, new variants with differing transmission rates, or the deployment of vaccines.

What about your field of study most fascinates or interests you?

(Weitz) I remain fascinated by how viruses one thousand times smaller than the width of a human hair can have global-scale impacts. The world is teeming with viruses and precisely because of their diversity and numbers, we need mathematical models to bridge the gap between many countless interactions and global impacts.

(Beckett) How small individual interactions can scale up into large-scale impacts; and how systems are made up of multiple types of interactions that can feedback on the systems’ dynamics. I also find it wonderful how many insights can be gained, even from simple mathematical models; and how simple microbes can be part of potentially very complex interactions.

(Harris) I’m really interested in the feedback between human activity and infectious diseases. Infectious diseases shaped the course of human history in so many ways, but we also have the power collectively to change how epidemics play out – for better or worse. Preventative measures, especially vaccines, are incredibly powerful. For example, we successfully eradicated smallpox, which was a tremendous accomplishment. On the flip side, we’ve been transforming the planet by releasing greenhouse gases and clearing forests, processes that can also have major impacts on disease transmission. I’m interested in studying those feedbacks and trying to quantify their impacts.

How is global warming going to affect the spread and severity of infections? Do you expect certain communicable diseases to spread further as the temperatures increase?

(Harris) Climate can affect transmission rates of diseases directly—for example, influenza transmits best at certain levels of humidity and mosquitoes that spread diseases like malaria and dengue are really sensitive to temperature because they are cold-blooded. Climate change is therefore expected to shift risk of these diseases across time and space, not necessarily just increase disease across the board. For example, it may actually get too hot for malaria transmission during certain parts of the year even while temperature becomes more favorable for mosquitoes that carry viruses like dengue and Zika.

In addition to those changes based on the direct relationships between climate factors and the biology of vectors and pathogens, we may also see shifts in disease risk connected to human behavior. For example, if people are spending more time indoors because it’s too hot, you may see an uptick in respiratory disease transmission. In the aftermath of extreme weather events, people are often displaced, infrastructure may be damaged, and public health activities may be interrupted. Preparing for these changing disease risks is an important part of climate adaptation. If you want to learn more about this, check out this BBC article I was quoted in this week!

How could we have prevented the COVID-19 virus from spreading on a massive global scale? Would following the quarantine have stopped the wide spread?

(All) COVID-19 was and is an incredibly challenging pathogen. Unlike SARS-1, COVID-19 had significant presymptomatic and asymptomatic transmission. Moreover, individuals could have mild/asymptomatic infections so that they felt fine and nonetheless could infect others. The ‘silent’ component of COVID-19 made it very difficult to contain, especially with conventional symptom-based containment measures. Yet we should also recognize that we have had more intervention ‘levers’ from the start, even before the widespread availability of vaccines. For example, less intrusive measures like mask-wearing, rapid antigen testing, risk assessment and communication, paid sick leave, and air filtration can reduce transmission while allowing people to resume some semblance of normal socioeconomic activity. We continue to engage with economists and policymakers to assess the joint public health and socioeconomic impacts of decisions. But, in doing so, it is key to reiterate that there are many steps we can take to protect individuals and communities that will be of service not only in responding to COVID-19 but also in preparing to prevent pandemics to come.

What are some exciting new trends or prospects in modeling techniques for infectious disease models? Which techniques are going to become more relevant in the future?

(Beckett) I think that multiple modeling techniques are going to play a role in developing (and fitting) epidemiological models of the future. For me, one of the more exciting trends has been the emergence and integration of novel datasets into models—whether it was something like mobility data e.g., via Google, or the widescale emergence of wastewater surveillance systems able to measure viral concentrations in wastewater. In terms of analyzing population transmission, most available datasets have considerable uncertainty, whether that be in magnitude (e.g., bias of testing towards symptomatic individuals, and limited data from self-tests) or timing (e.g., reporting of cases follows the time to collect and analyze them). Combining multiple streams of evidence can help to constrain model-fitting, and provide more realistic forecast estimates useful for response. I also see potential in multi-model averaging techniques, such as those used in the COVID-19 forecasting hub, to help constrain and assess such estimates across multiple models with differing assumptions (which may be more, or less, relevant depending on the disease context).

(Harris) Since disease dynamics are so complicated, and are often influenced by multiple interrelated drivers at once, I’m also excited about using relatively new causal inference methods that allow us to more precisely estimate the effect that human behavior is having on infectious disease burden. This is particularly relevant in the emerging field of climate-health attribution—trying to measure the impact that climate change has already had on infectious disease burden.

What do you feel are the most important scientific conclusions from the COVID-19 pandemic within your field of study, and how do you think these might or should affect our position on any future pandemics?

(All)

The importance of asymptomatic transmission routes was a key differentiator from SARS-1 where the bulk of transmission occurred AFTER the onset of symptoms.

Airborne transmission led to multiple superspreading events which can accelerate the distribution of infections across groups.

During COVID, we saw very clearly a gap between harm to individuals vs. risk to populations as a whole. We still need to do a better job of ensuring that we do not conflate individual and population outcomes.

Across different groups, we saw variability in immunity and the difference between risk of infection, transmission, and severe outcomes. The latter is a subtle but important distinction.

Social behavior plays an important role in epidemic dynamics, and there is a need for greater collaboration in this space.

It was challenging to deploy academic scientists via ‘secondments’ to aid in times of national crisis—the infrastructure for supporting this kind of work remains largely incompatible with current academic obligations. New approaches to connect academic, industry and government are needed to enable this kind of rapid deployment.

There is a need for ready-to-deploy epidemic modeling frameworks (see above regarding comparison of epidemic modeling approaches).

We also need integrated and timely frameworks for collating and publishing key epidemic data at scales from counties to states to nations in time of need. These data are critical to fit our models. For COVID-19, this was mostly done via volunteer efforts in the US (e.g., The COVID Tracking Project) and then collected via academic sites (e.g., The JHU COVID-19 Dashboard), as well as by other national-level news agencies (e.g., the New York Times and Washington Post). Standardization, access, and exchangeability of data should already be a priority to prepare for future outbreaks.

Positively, we are heartened by the fact that so many scientists, engineers and others engaged in seeking to understand and mitigate risks from this pandemic, bringing their own disciplinary expertise to this interdisciplinary challenge.