How a Newly Spotted Space Rock Went From Terrifying to ‘Quite Interesting’

Skywatchers got a chill (or perhaps a flashback to the Bruce Willis-helmed ’90s blockbuster, ”Armageddon”) last week when astronomers suddenly boosted the chances of a recently discovered asteroid hitting Earth in late 2032—one big enough to potentially devastate a city and kill hundreds of thousands—to 1-in-30.

This week, though, new observations of asteroid 2024 YR4, believed to be between 130 and 300 feet in diameter, led NASA scientists to reclassify its risk as essentially nil.

While that’s reassuring, consider that thousands of even larger objects still lurk unspotted in the vicinity of the Earth, despite years of intense work to catalogue threats, said a University of Maryland astronomer.

“We previously reached a 90% level of knowledge of near-Earth objects of a kilometer or larger, but for smaller objects … we’re not even close to that,” said James “Gerbs” Bauer, who specializes in studying nearby comets, asteroids and other objects.

Bauer, who manages the Small Bodies Node—part of NASA’s Planetary Data System that's been providing the latest information on the new asteroid—sat down with Maryland Today to explain why risk assessments varied so widely, the hazards we face from other unknown asteroids and how we might head off another space boulder on a collision course with Earth.

Was this like a near miss? Were experts worried at any point about Earth’s safety?

Yes, it was actually a concern, and something quickly noted as an object of interest. The community quickly got involved in following this one.

How did the risk assessment balloon to more than a 3% chance of impact, then plunge to a tiny fraction of a percent?

I like to use the analogy of tracking a fly ball in baseball. It’s not clear in the tenth or hundredth of a second after the ball is hit what the path will be. You track it for a little while, and at the top of its arc, you have an idea which fielders will try and catch it. Even as it becomes more certain where it’s headed, you still have to keep your eye on the ball.

With objects in space, when it’s nearby and easy to see, the angular velocity is very fast, so you might get some timing errors or uncertainties when estimating the path. As we increasingly understood the full arc of the asteroid’s path because of new observations, the uncertainty area where it could go tightened, and as it did, Earth filled up more of that area, causing the chance of an impact to grow. But then the uncertainty area tightened even further and started to fall off the Earth. That’s what you saw happening when the risk suddenly dropped to near zero Monday.

With all the up-and-down impact probabilities since the asteroid’s discovery in December, any possibility of risk bouncing back up?

It may change very slightly, but it would be very odd for it to go back up to the probability it was at for the 2032 close approach. Its orbit will keep bringing it back into the vicinity of Earth, but each of those approaches will have an even lower impact probability by factors of perhaps 10.

So we can forget about this asteroid.

Although it’s no longer a threat, a pass that is expected to be just inside the orbit of the moon is quite interesting to study. Another well-known asteroid that was once thought to be a potential impactor, Apophis, will come even closer in 2029, and a number of programs are preparing to study that, including with spacecraft. It will pass within 38,000 kilometers, or about six Earth radii.

That’s shaving it close. What is the risk of other asteroids we don’t know about yet?

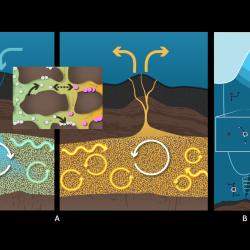

We know about most of the larger objects, but for those between 140 meters and 1 kilometer in diameter, we have maybe found 40% with orbits in the vicinity of Earth. Some of those smaller objects, if they hit near a city, could cause a lot of devastation regionally. If they’re close to one kilometer, they’re a global hazard. There’s a mission called NEO Surveyor coming up that will look in the infrared for objects down to that size and even smaller. The goal is to get to 90% knowledge of what’s out there.

What can Earth do if a dangerous asteroid or comet is incoming?

We have a number of options. We could send a kinetic impactor to try and change its course. Even more subtly, if you have a lot of lead time, you could use a “gravitational tractor”—you place a massive spacecraft alongside and it slowly exerts a gravitational pull so you can nudge the asteroid out of the way.

It’s important to realize we have a lot of people and organizations involved in planetary defense. More positively, all of this reminds us that although we live on Earth, we’re interacting with space and space is interacting with us every day. There’s a lot of fascinating things to find out there, even as we’re working to protect ourselves.

Written by Chris Carroll