What It Takes: The Insect Zoo

A barely noticeable black dot scurries across a beige floor, easily mistaken for a bit of fluff or fleck of dirt. But not to the keen eyes of the staff and students of the University of Maryland Insect Zoo.

“Oh! There’s an isopod on the ground!” exclaims zoo manager Todd Waters, as student volunteer Julia Chan ’25 bends down to scoop it up. “That might be a Madagascar hissing cockroach baby, actually. Oh yeah, it looks like it.”

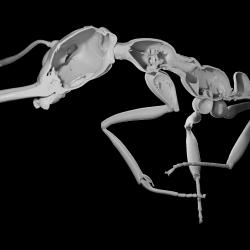

For many people, just the thought of a roach nearby is enough to make them shudder or shriek. But that fear is what the folks at the Insect Zoo are hoping to change by carefully cultivating a collection of about 100 species—like beetles, grasshoppers and mantises, and non-insect arthropods, such as centipedes, scorpions and spiders—and introducing them to the public. They take the critters all over Maryland, presenting them at elementary schools, agricultural fairs, community events and more, and open up their facility to classes and tours.

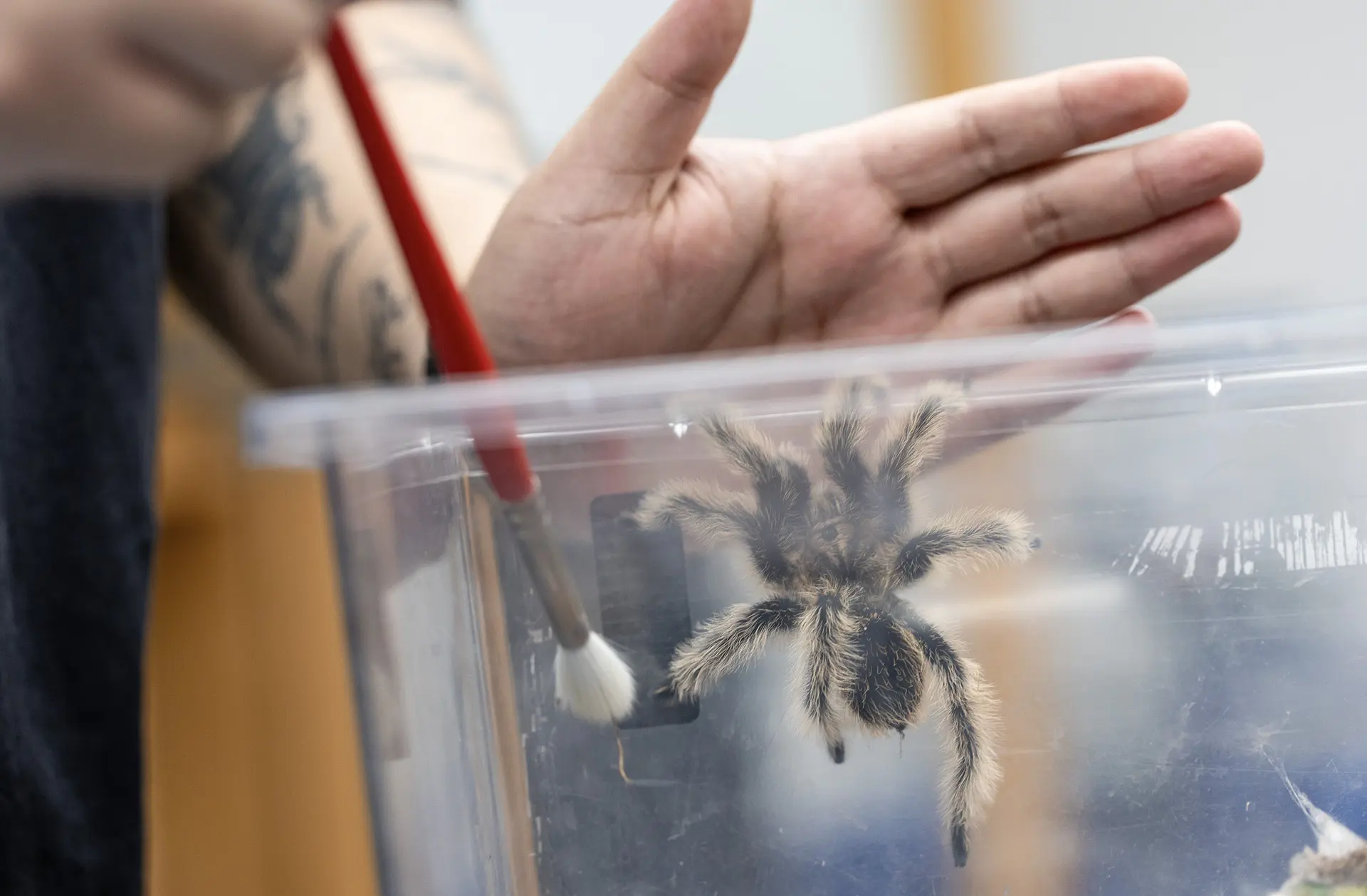

They get some of their biggest crowds of the year at Maryland Day, when 80,000 people stream through campus. Lines for the Insect Zoo exhibit regularly snake around the Plant Sciences Building as eager kids and patient parents wait for their chance to hold a furry tarantula, peer through the water at a dragonfly nymph or examine iridescent butterfly wings.

As Maryland Day prepares to return on Saturday, Waters, a College of Agriculture and Natural Resources faculty assistant; Chan, a government and politics major and entomology minor; and student worker Ryan Lee '26, an art history major, share the challenges of gathering the right leaves for their pickiest eaters, why one of their insects spends time on a tiny treadmill and which of their brood is the most misunderstood.

Waters: The first time someone emailed that they wanted to have someone come out and talk about the bugs with their elementary school class, I thought: I’m not an entomologist. I have a bachelor's degree in genetics. I had only been working at the Insect Zoo for a couple of months in 2017 when Professor J. Lee Hellman, who started it, retired. It was a much smaller operation. But then the second time, I was like, “You know what? I think I can do this.” It went really well and it gave me a strong sense of purpose. Every single event we have, there is at least one, if not a handful of people, who go from, “I hate bugs, I'm never holding bugs” to, “Wait, this is really cool, I love this!”

Lee: I come in three times a week for one to three hours. Part of my job is to feed the animals and give them water. It's not like a cat or a dog where it's like, feed once in the morning and once at night. It’s a lot more of: Is this tarantula looking kind of fat, or are these cockroaches beginning to eat each other?

Waters: There’s a lot of intuition and adjusting that goes into their care.

Lee: We have predators, like scorpions and tarantulas, which eat crickets or excess feeder roaches. Then you have herbivores, which we mainly feed leftover produce and occasionally fish flakes. The stick insects, the phasmids, Todd usually feeds because they really need specific types of leaves.

Waters: For the Northern walking stick, for example, they primarily eat maple or oak leaves, but they hatched earlier than we thought, so we’ve been struggling to find food for them. They’ll also eat bramble, like wild raspberries or blackberries, and there’s one bramble bush on campus, so I go there every three or four days. They can also eat rose leaves; luckily we knew someone in the greenhouse who could bring us rose clippings.

Lee: Occasionally I help with breeding. For the tarantulas, for example, we try to fatten up the female as much as we can beforehand. It’s even more risky with the mantises. We have to feed her big fat crickets while they do their dance so she doesn’t make a snack out of the male.

Waters: We take the insect collection out to community events once or twice a week from the spring to the fall. We partner with the U.S. Forest Service, that has a set number of schools they work with, but we also have a huge list of our own. It’s often elementary and preschools, and we work with county Extension offices to present at pollinator days, STEAM festivals and more. We bring 10-20 types of bugs to each event and two or three student volunteers.

Chan: We show the bugs to people, answer questions, wrangle the crowd. Children tell us about their little bug experiences.

Waters: They really go crazy if things poop. The Hercules beetle larvae makes a giant poop and they scream and call their friends over to watch it. They also love the Lubber grasshoppers because they jump at random times.

One of the cutest things I ever saw was this little girl who was eager to hold a tarantula. And her dad looked like this big tough biker dude, but he didn’t even come close to the table. Eventually she got him to come and they traded off the tarantula, holding it, for maybe 10 minutes. This little kid helped the adult get over their fear.

Chan: My favorite experience was at the Maryland Agricultural Fair, where there was this small child who was bringing random people over. She’d teach them all the facts we just told her. She held everything, even one of the beetles that almost feels like it’s pinching you. I’d try to help her, and she’d be like, “I got it!”

Waters: We prepare for Maryland Day all semester. In February and March, we start pulling eggs out of the fridge, where they stay in the winter, so they can hatch, and increase our collection by getting insects from other zoos, since many die naturally in the fall when it gets cold.

Entomology Professor Paula Shrewsbury is our main organizer for Maryland Day. It takes a lot to set up. The week before, I’m working 80 hours to get all the terrariums cleaned and ready. On the day of, we’ll have 20 or more student volunteers, who man the whole hallway with all the different animals, and different labs help out with displays on mosquitoes, honeybees, or butterflies and moths.

Tarantulas are the biggest hit. Stella and Rosie are both 22 years old—they can live up to 30—and while Stella is a little more skittish, Rosie is used to be being handled. Last year alone, she was in 7,000 people’s hands.

Lee: Kids also love these blue death feigning beetles. Because of the name people think they’re a killer bug, but they just play dead when they’re scared. They’re great for kids to handle because you can’t accidentally crush them.

Waters: While the zoo is mostly used for outreach, we also partner with some of UMD’s entomology classes to conduct labs. One of them borrows our vinegaroons for a session on arthropod locomotion, and they put it on a tiny treadmill to see how it runs, how its joints and legs move. Everyone thinks they look scary but their only defense mechanism is shooting out this concentrated form of vinegar.

Lee: Another animal that’s really misunderstood is the black widow. A lot of people think immediately, “Oh, she’s gonna come and kill you.” But they mostly want to hide and don’t like human disturbance. They’re terrified of us.

Chan: Things that look freaky, it’s always, “Kill first, ask questions later.” Are cockroaches really being dirty? No. They actually clean themselves, like a cat.

Waters: They’re creatures with interesting lives and different personalities. To get a chance to show people, it’s pretty magical and wonderful.

This is part of a series that looks behind the scenes at “what it takes” to keep the University of Maryland humming and create a vibrant campus experience. Got an idea for a future installment? Email kshih@umd.edu.

Written by Karen Shih ’09