Finding the Right Chemistry at UMD

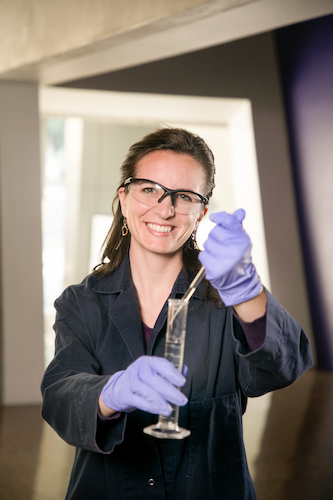

With her research group tackling grand challenges and a new state-of-the-art lab in her future, materials chemist Mercedes Taylor is on a roll.

A year ago, as construction crews demolished Wing 1 of the University of Maryland Chemistry Building, assistant professor Mercedes Taylor found it hard to look away.

“I was standing in somebody else’s lab looking out the window, and they had a front row seat,”

Taylor recalled. “I kept thinking, how could you get any work done, you would just watch that all day long.”

Now, as she watches the activity at that same construction site, Taylor sees much more than a new Wing 1 taking shape, she sees her future.

“I’m thrilled, and the other members of my research group are, too, especially now that it’s really a physical presence,” she said. “All the stories of the building are there now, and each day there’s a little bit more embellishment. I’m enjoying seeing it every day and kind of dreaming about it.”

It’s more than a dream, though. Taylor’s lab, which develops novel materials for water purification and energy, will be one of many relocating to the new Wing 1 after it’s completed in late 2023. And she can’t wait.

“We’re going to be moving into a brand new state-of-the-art lab space,” she explained. “We’ll be working and collaborating with other researchers who are doing synergistic research and different types of materials synthesis and organic and inorganic chemistry. It’s very exciting.”

For Taylor, the new lab will mean new opportunities to advance her mission as a scientist—tackling grand challenges that impact us all.

“My mission is to address global collective problems related to energy and sustainability,” she explained. “And if you have the opportunity to use science to solve a communal collective problem, that’s a great opportunity.”

Finding her niche

Taylor didn’t plan on being a chemist. In fact, when she left her home in Falls Church, Virginia, to attend Amherst College in Massachusetts, she wanted to major in political science. But an undergraduate chemistry class unexpectedly captured her interest. Then a summer job in a materials lab and an opportunity at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) after graduation sealed the deal.

“NIH has this thing called the post-baccalaureate program, where you can work for a year or two in a lab as a full-time scientist, understanding what that would really be like,” Taylor recalled. “It was an excellent opportunity, and I’d really like students at UMD to know about it, because it changed my life. It made me certain that I wanted to go to grad school and become a chemist.”

Energized by her NIH experience, Taylor headed to the University of California, Berkeley, for her Ph.D.

“I went there with the idea of joining the lab of Carolyn Bertozzi, who just won the Nobel Prize,” Taylor explained. “But I really wanted to get into materials, so in the end I joined another excellent professor’s lab instead, Professor Jeffrey Long, and I learned how to make these types of porous materials that I now study.”

After earning her Ph.D. in 2018, Taylor continued her porous materials research at Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

“I had a special fellowship where I was allowed to work on my own ideas, and what I wanted to do was use a porous material to capture ions out of water for the purpose of purifying the water and obtaining the ions,” Taylor recalled. “The experience was empowering. It made me feel like I’m capable of coming up with my own projects and seeing them through.”

In 2021, when Taylor saw an opportunity at UMD to teach and continue her research closer to her home and family, it was a challenge she wanted to take on.

“There’s definitely something that’s very intimidating about being a faculty member at a university, originating all the ideas and running a whole research lab,” she said. “But I had gained confidence in that area, and the research freedom of being a faculty member was becoming more appealing for me, as opposed to being at a company or a more industrial research situation. And I was really excited about being back home in the DMV area.”

Hitting the ground running

When Taylor arrived at UMD in July 2021, she hit the ground running, starting her research lab from the ground up.

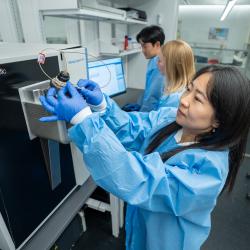

“I hired a postdoc named Andrea Zeppuhar right when I was arriving,” Taylor recalled. “She and I got rolling almost at the same time in a completely empty lab, then my three Ph.D. students joined us. The five of us have experienced this transformation from a scary empty lab with no projects started to where we are now, which is really on a roll making progress in lots of different directions.”

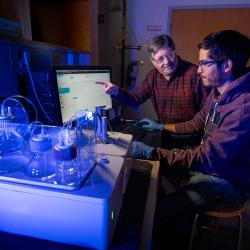

Using the tools of coordination chemistry and organic synthesis, Taylor’s lab designs novel materials such as metalorganic frameworks, covalent organic frameworks and porous polymers for use in water purification, extracting precious metals from seawater and ion conductivity in batteries.

“My team and I are trying to design materials that will be able to capture certain guest molecules out of a complicated soup of different ions and contaminants,” Taylor explained. “One of our major goals is to purify water, and another goal is to be able to get valuable ions out of water sources like wastewater or industrial waste -- things like cobalt, which is very valuable and is important for clean energy technology, and I care a lot about that.”

Taylor also cares about the future of science itself and specifically about encouraging more women and students from underrepresented groups to pursue careers in science. In March 2022, she was one of 120 women honored by the American Association for the Advancement of Science as ambassadors for the If/Then program, promoting women in STEM.

“It was a great honor,” she reflected. “I was selected with a bunch of other women scientists because we were doing outreach and we were reaching young women and girls, encouraging them to pursue STEM, and that was the whole concept.”

“Everyone should be able to become a scientist”

Taylor also works with local high school students, helping them see science in their future.

“I think everyone should be able to become a scientist, and I’m trying to help students do that,” Taylor noted. “Right now, I’m working with high school students in Prince George’s County to help them recognize ways they could continue in science and become scientists, and also to help them see the world through a scientific lens.”

Though much of Taylor’s time is devoted to her work, she also recognizes the importance of finding time for herself.

“I still enjoy reading, just like I did in college when I wanted to be a political scientist, and I’m trying to get back to the sports I used to enjoy,” she explained. “I joined a basketball team recently and on the court my shoes fell apart, and I realized those shoes are actually from my sophomore year of high school. So, I guess I’m going to have to get some new shoes.”

Though the jury may still be out on Taylor’s future success on the basketball court, her work in research and in the classroom is on a roll. With the new Chemistry Building and a state-of-the-art lab in her future, it just keeps getting better.

“I really think being in the new building is going to help me take my research to the next level,” she said. “There’s going to be outstanding instrumentation, we’ll have the ability to study our materials more thoroughly and understand even more chemical information about where the atoms are and what that means for their properties, and we’ll have more opportunities to collaborate and work together. It’s going to be really fun.”