Fighting COVID-19 in the ER: UMD Alumnus Larry Edelman’s Story

Baltimore emergency physician shares the fears and challenges of working on the front lines

“It certainly is scary not knowing what could happen on a given day.”

span style="font-size: 1em;">After 11 years in the emergency room, Dr. Larry Edelman (B.S. ’01, biochemistry) has learned to expect the unexpected. Just not this.

“It was really never on my radar, though it should have been,” said Edelman, who earned his M.D. in 2006 from the University of Maryland, Baltimore. “I’ve envisioned all types of disaster situations, from terrorism nearby to multiple traumas. One of the scariest things you worry about these days is being in the middle of a mass shooting. I think anything like that was far more on the radar than a worldwide infectious pandemic. In recent years, SARS, MERS and Ebola have spared the United States.”

But there it was. Watching news reports about the coronavirus outbreak in Washington state, Edelman realized COVID-19 could hit home.

“I think once it hit the United States, it became much more of a reality,” Edelman explained. “I started paying attention to the news of what was happening in China at the end of January. With reports of the Seattle nursing home outbreak in February, I realized there was the possibility of it becoming a problem here in Maryland. If there is a major pandemic, mass casualty situation or disaster in your local area, it’s going to come through the ER.”

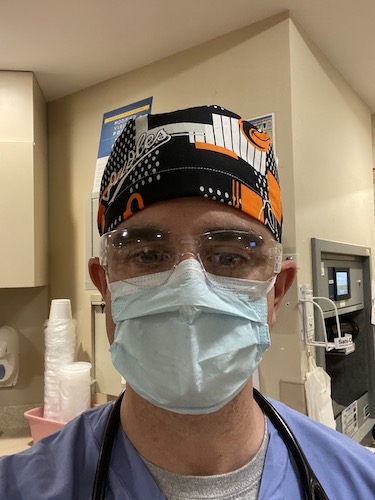

Edelman works the night shift as an emergency physician in two hospitals north of Baltimore. He has dreamed of being a doctor since he was a kid.

“When I realized I wasn’t going to be a baseball player, I think I always knew I wanted to be in the health care profession,” he said.

Volunteering at Holy Cross Hospital as an undergraduate helped confirm Edelman’s decision to go to medical school and eventually pursue a career as an emergency medicine physician. Now, he’s one of countless health care professionals fighting the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s intense, he said, but not as bad as New York City or other hot spots around the country.

”However, we still expect it to get worse before it gets better. We are seeing a steady stream of COVID-19 positive or presumed-positive patients. I think as I work each day there’s a slightly higher percentage,” Edelman explained. “Usually pneumonia or influenza causes respiratory failure or sepsis over a few days period. Patients with COVID-19 tend to be more likely to present to the emergency department in respiratory distress and they become critically ill very quickly. Also, when we see them in the hospital, they are no longer allowed to have any visitors due to the restrictions, so they are alone and scared.”

In the ER, stress levels are high, shifts are busy, and the fear is very real.

“I think my colleagues’ biggest fear is bringing it home to their families. I think most of us are saying we’re young and healthy and we’ll be fine. It is probably true we will be fine if we get sick,” Edelman said. “But there is a higher incidence of frontline health care workers who get coronavirus who are becoming critically ill or dying than the general population. Because they’re exposed to back to back patients who are very sick and are shedding a lot of virus.”

Personal protective equipment is essential. Thankfully, at his hospitals, they have enough to go around. But shifts are nonstop, and breaks are few and far between.

“The emergency department, under normal conditions, is busy with few breaks for the workers to use the bathroom or eat. Usually, we can stay hydrated during our shift and drink coffee while documenting or placing orders in the computer. Now, we must wear a mask all shift and minimize touching our faces to prevent contaminating ourselves. So, now I try to avoid eating or drinking during the entire eight- to 10-hour shift,” Edelman said.

Every day, every shift, Edelman does what he’s trained to do and tries to keep himself safe.

“You just take it one day at a time and try to get through. You hope you don’t see anyone too sick and you hope you don’t make any mistakes at work that would cause you to contaminate yourself,” Edelman said. “And when you see your relief, you’re happy and try to get your stuff wrapped up and try to get yourself home.”

Even going home after a long shift in the ER comes with a new routine for Edelman—who is taking extra steps to keep his wife and 2-year-old daughter safe and hoping it’s enough.

“Now when I get out of my car, I close the garage door, strip down to my underwear, wipe down my car with sanitizer and jump straight into the shower,” Edelman said. “Whether or not I should be sleeping in a separate bedroom is a conversation I have daily with my colleagues. A few have moved to the basement or a different bedroom. It would be a much easier decision to move to the basement if my child was older and self-sufficient. I don’t think my wife or child are ready for me to truly isolate myself. My child is two and she wouldn’t understand, so I would have to essentially disappear into a hotel room or the basement.”

It’s unlike anything he ever imagined, but like other health care professionals and the rest of us, Edelman is doing his best to adjust to the new normal as the COVID-19 situation continues to change.

“We’re getting better at testing and the turnaround time is improving,” Edelman said. “But I think it will be awhile before we see the number of deaths start to decline.”

And while the daily reality of COVID-19 reminds him of the risks, it also strengthens his commitment to making a difference for as long as this outbreak continues.

“The health care workers who have contracted coronavirus while at work and became critically ill or passed away from this disease are heroes - no question about that,” Edelman said. “In my opinion, the rest of us are dedicated workers who made a commitment to ourselves, our profession and our community. As a society, I hope we can learn from this experience.”

###

Media Relations Contact: Leslie Miller, 301-405-9267, lmille12@umd.edu

University of Maryland

College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences

2300 Symons Hall

College Park, MD 20742

www.cmns.umd.edu

@UMDscience

About the College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences

The College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences at the University of Maryland educates more than 9,000 future scientific leaders in its undergraduate and graduate programs each year. The college's 10 departments and more than a dozen interdisciplinary research centers foster scientific discovery with annual sponsored research funding exceeding $175 million.