International Lightning Safety Day: ‘When Thunder Roars, Go Indoors’

UMD postdoc Daile Zhang shares her fascination with lightning and tips on how to stay safe during a storm

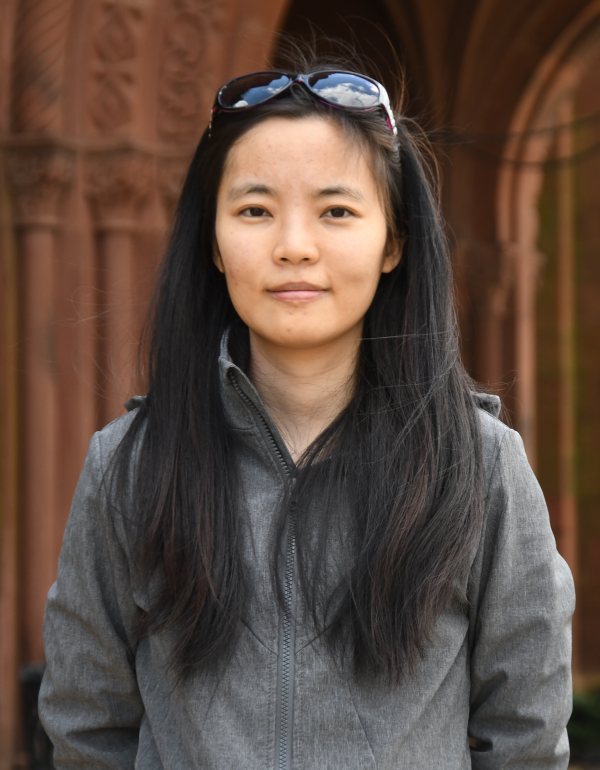

Summer is traditionally associated with sunny days and relaxing vacations. But for Daile Zhang, a postdoctoral associate in the University of Maryland’s Earth System Science Interdisciplinary Center (ESSIC), it’s one of the busiest times of the year.

“Summer brings a lot of moisture and warmth, which are both very important ‘ingredients’ of storms,” Zhang explained. “About two-thirds of lightning that happens over land in the U.S. occur during the summer months. And because I study storms, how they form and where they go, I end up tracking a lot of them during the season.”

Zhang, a meteorologist and fulminologist (a scientist specializing in lightning research), uses both land-based and satellite-based lightning locating systems to detect brewing storms across the country. Her Atmospheric Electricity Research & Training group captures lightning strikes and storms using cameras around UMD’s College Park campus and across the country. The team also operates a ground-based network of sensors called the Mid-Atlantic Lightning Mapping Array (MALMA), which detects and geolocates a range of radio frequency electromagnetic waves known to be produced by lightning. With eight stations deployed in the D.C. metro area and 17 stations on Wallops Island, Virginia, MALMA provides detailed maps of total lightning activity within the region.

“We’re basically detecting lightning as it occurs in real time and in 3D,” Zhang said. “Systems like MALMA let us know the time, location and strength of the signals detected, and from that information, we can generally figure out a possible area of where lightning might be present.”

Finding the future of fulminology

Since childhood, Zhang was intrigued by the skies and what they had to offer, from wind to water. Her fascination with storms really took off when she was a Ph.D. student in atmospheric science at the University of Arizona concentration in remote sensing. She was particularly struck by the bold images of lightning streaking across Arizona skies.

“Arizona is often called the ‘Lightning Photography Capital of the U.S.’ for a reason—it has a real presence there, from a Native American lore standpoint to how it causes wildfires,” said Zhang, who recently co-authored a book on the cultural and scientific role of lightning in the state. “Lightning is visually striking and yet very impactful when it comes to how it has shaped societies, both figuratively and literally.”

Zhang’s professors also introduced her to the darker side of lightning: its dangers. Inspired by their work in lightning safety, Zhang dedicated herself to finding ways to reduce damage from severe storms and eventually became a member of the National Lightning Safety Council.

Now at UMD, Zhang continues to study lightning and storms with her ESSIC team while promoting lightning-related science education and outreach efforts on lightning safety awareness. Her team coordinates with other atmospheric electricity research and weather authorities including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and NASA.

Zhang and her team are currently collaborating with the National Weather Service on a virtual reality (VR) project to improve visualization of weather and climate data. By using a VR platform to display information on hurricanes, atmospheric river and climate patterns, researchers and forecasters will be able to organize the data on a larger scale and share it with other scientists more quickly. The VR aspect, as well as the ability to upload the data into a large cloud accessible to offline users, will make the information easier to work with and store.

The team is also working on an aviation safety project to help airplanes avoid dangerous storms by detecting and flagging threatening weather affecting specific airports and flight paths. Using satellites like the Geostationary Lightning Mapper and ground-based networks like MALMA to pinpoint emerging storm conditions, meteorologists can work with air-traffic controllers and pilots to create no-fly zones and develop better warnings to alert pilots to hazardous storms on their routes.

By improving accessibility to potentially lifesaving information and tools, Zhang hopes to help other forecasters at different locations across the globe improve their understanding and predictions of upcoming weather events.

“I’m working to make all this satellite-based data we have easy to access for everyone around the world,” she said. “Studies have shown that this data can increase the lead time we have over severe weather hazards. This not only mitigates the number of potential lightning fatalities or injuries, but also other lightning-related weather hazards like hail, strong winds and tornadoes.”

Dispelling lightning myths

As thunderstorms roll in this summer, Zhang wants to clear up a few popular misconceptions and myths about lightning. First, don’t believe everything you’ve heard.

“People often say lightning never strikes the same place twice—unfortunately, they are very wrong,” she said. “Features that stand out from the ground, such as trees or buildings, are actually more likely to be repeatedly struck by lightning. An example of this is the Empire State Building, which is why it’s also a favorite subject of lightning studies.”

Zhang also says if you’re caught outside in a thunderstorm, the safest thing to do is head toward a building where there are lightning safety installations like lightning rods and cable conductors to help direct electricity safely away from people. In a flat area, lightning is more likely to strike a raised object, but Zhang warns that any object can be hit by a bolt of lightning.

“There is no safe place outside,” Zhang explained. “It’s not safe under a tree or in a tent. In fact, 10% of all lightning fatalities and injuries around the world are related to trees—lightning can ‘jump’ from a trunk to a person and it doesn’t need to strike you directly to hurt you. You should find an enclosure encased in metal and that also very good grounding to make sure you’re safe inside, like inside a car or building.”

Another myth that Zhang hopes to straighten out is the idea that rubber-soled shoes or rubber tires can save you from lightning. She adds that the rubber actually provides little to no protection at all from lightning. Instead, the metal exterior shell of your car is responsible for conducting an electric charge away from you and leading to the ground via the axles and tires. The same logic applies to commercial airplanes, she adds, because the metal exterior conducts lightning strikes so that they dissipate harmlessly into the air.

Fortunately, Zhang believes that efforts to educate the public about lightning safety are working—and saving lives.

“In 2006, there were 49 lightning-related fatalities in the U.S., but only 19 last year in 2022,” she said. “This shows how important increased accessibility and exposure to critical information can be, and why my team and I will continue to do this important work.”

To learn more about Zhang's work with lightning, please view the video below of 360-degree footage taken from UMD campus cameras during a storm in July 2021.