Building Sustainability by Serving the Community

From rescuing dining hall leftovers to researching plant viruses, junior biological sciences major Kyle Zibell tackles waste on multiple fronts for a more sustainable future.

When the University of Maryland’s South Campus Dining Hall closes at 9 p.m., junior biological sciences major Kyle Zibell’s work begins.

“I’m the UMD Food Recovery Network’s head recovery leader for the South Campus Diner,” Zibell explained. “We’re student volunteers who come to the dining halls, pack up extra uneaten food from the day and deliver the food to a local church where it’ll be redistributed to food-insecure communities in the area.”

In 2024, Zibell helped orchestrate operations that salvaged an impressive 28,000 pounds of food from the campus dining halls—translating to approximately 23,000 meals distributed throughout the D.C., Maryland and Virginia region. First started at UMD in 2011, the student-run Food Recovery Network has since grown into a nonprofit organization with a chapter in almost every state. The group’s organizers, including Zibell, and their efforts were recognized at UMD’s 13th annual Do Good Challenge in April 2025, where they took the $10,000 first place prize in the competition’s Leaders track.

The South Campus Dining Hall also supports a unique individual meal collection program—it’s the only one at UMD that provides meals specifically for food-insecure UMD students through the Campus Pantry. An estimated 20% of UMD students lack reliable access to sufficient quantities of affordable and nutritious food, and the pantry is often the first resource they turn to for help.

“My big personal project is expanding individual meal collections,” Zibell said. “We’re working to move from just one or two days a week to collecting every day of the week. We also hope to grow beyond the 15 organizations we currently work with to redistribute food and to bring our work to all UMD events, including Maryland Day and athletic events.”

Zibell’s commitment to addressing food waste began in high school, when he worked on a composting system that recycled unwanted kitchen scraps into fertilizer. When he arrived at UMD, Zibell realized he wanted to tackle problems beyond food waste. During his first semester, he joined the Food Recovery Network when he learned that the group worked to redistribute food to the people who needed it the most.

“Food scarcity is a big issue I focus on because it’s personally related in my life,” Zibell explained. “I believe that access to food is something that should be a central human right and it’s my goal to bring us closer to a world where everyone has the food they need.”

Battling invisible threats to the food supply

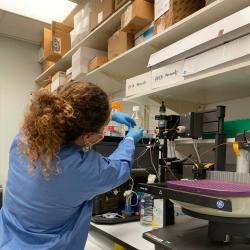

Beyond recovering meals at campus dining halls, Zibell works on the other end of the food chain as well. In Cell Biology and Molecular Genetics Professor Anne Simon’s lab, he studies the plants that make up the world’s food supply and the diseases that threaten them.

“Dr. Simon’s research group focuses on novel RNA viruses and how they impact and kill different plants,” Zibell explained. “For example, citrus trees are heavily affected by many of these RNA viruses, causing massive destruction and loss of citrus crops.”

Zibell is working with Simon on characterizing a virus from a recently discovered group of RNA plant diseases called umbra-like viruses (ULVs), which have some key differences from other plant viruses. Most traditional plant viruses have three key components: a polymerase (which helps them reproduce), a coat protein (which protects them) and movement proteins (which help them spread throughout the plant). In his research, Zibell studies one ULV in particular to better understand its attributes, such as its structure and stability.

“We’re working on a virus that’s been isolated from grapevine. It’s the first in a class called group 1 umbra-like viruses to be characterized,” Simon explained. “Kyle is pioneering the protocol to figure out whether the ULV has a coat protein like a traditional virus does.”

Mapping out the virus’s unique properties (such as its shape, size, genome, life cycle and interactions with hosts) will help researchers understand how it spreads and eventually how to counter it. For Zibell, the work has implications for millions of people around the world, well beyond the laboratory.

“These diseases cause significant plant loss and they’re only increasing,” he noted. “Everyone will be impacted by these viruses in one way or another, but especially because they can decimate the crops we rely on for food. It’s crucial to work to prevent that.”

Charting a path forward

Looking ahead, Zibell hopes to continue supporting the community around him with the leadership skills and scientific training he received from UMD. Last year, he began work as a certified EMT with the Montgomery County Fire and Rescue Service to get hands-on experience with providing care to human patients. Zibell says the experience opened his eyes to the economic, health and other societal disparities in his community.

“It’s not just about medical emergencies, like drug overdoses or shootings,” Zibell said. “Often, it’s really about helping people who’ve exceeded their own limitations—like a 70-year old who falls out of bed but has no family or friends nearby. Being there for all of them and keeping them safe has really made a difference.”

Zibell’s compassion and dedication to working toward a sustainable future has pushed him to take on one more personal project this year, a campaign to revamp UMD’s glass recycling program. After discovering that much of the campus glass ends up at landfills due to contamination, Zibell hopes to address the waste by fixing mislabeled signs and raising awareness in the UMD community.

“I think it all comes down to not being content with just identifying problems,” he said. “I don’t know how far I’ll go with my final year left here at UMD, but it’s something I’m extremely passionate about. Anyone can point out what’s wrong. The real challenge is figuring out what you can do about it.”