Biological Sciences Ph.D. Student Nick Bezio’s Research is an Art and a Science

Jellyfish had Nick Bezio pretty much from the get-go.

“It's never something you see in Vermont,” said Bezio, who grew up in Colchester, Vermont, where yellow perch are the most common creature in nearby Lake Champlain. “Jellyfish are just so weird and alien. I was instantly drawn to them.”

Now a first-year biological sciences graduate student at the University of Maryland, Bezio will study a different type of jelly called comb jellies for his Ph.D. But he’s bringing more than research skills to the project. An accomplished scientific illustrator and member of the Guild of Natural Science Illustrators, Bezio also brings jellyfish and comb jellies to life in science publications.

Bezio is co-author and scientific illustrator of the Identification Guide to Macro Jellyfishes of West Africa, published this year by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. With Bezio’s detailed black-and-white line drawings and richly colored paintings, the guide was compiled to help researchers identify more than 50 species of jellyfish that inhabit West African waters. With reports of a growing number of jellyfish blooms in the region—a possible indicator of climate change that could impact fisheries—scientists are looking more closely at what those jellyfish population changes mean.

Bezio is co-author and scientific illustrator of the Identification Guide to Macro Jellyfishes of West Africa, published this year by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. With Bezio’s detailed black-and-white line drawings and richly colored paintings, the guide was compiled to help researchers identify more than 50 species of jellyfish that inhabit West African waters. With reports of a growing number of jellyfish blooms in the region—a possible indicator of climate change that could impact fisheries—scientists are looking more closely at what those jellyfish population changes mean.

However, jellyfish aren’t always easy to identify. They may change shape or almost dissolve when removed from the water. To accurately illustrate the critical features of each species in the guide, Bezio gathered information from a variety of sources.

“Many of these illustrations are the first time they've been remade in well over a century,” he said. “It’s a combination of using original illustration work from a couple hundred years ago, like watercolor paintings that they made on boats back when they were initially discovering stuff and also utilizing resources given to me by the other authors. They were able to go collect specimens, dissect them and take pictures of them for me. Since experts also helped write it, we were able to fine-tune the morphology, the anatomy of the animals, before I rendered them, making sure the illustrations were not only beautiful but also that they were accurate.”

Bezio has always loved creating art. At Roger Williams University, where he majored in marine biology and environmental chemistry, he saw how he could put together art, science and jellyfish.

“I met my advisor, and he actually studied jellyfish,” Bezio said. “I also got to take one class in particular, an intro to scientific illustration, that just opened my eyes. Once I graduated, I knew I wanted to definitely pursue scientific illustration.”

Bezio went on to complete the Science Illustration Certificate Program at California State University, Monterey Bay. His next stop was an internship at the Smithsonian, doing scientific illustration for the Department of Invertebrate Zoology. Not sure what to do next, Bezio’s mentor suggested he go for his Ph.D. at UMD.

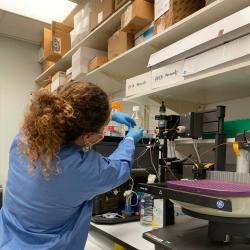

“I could utilize my interest for the weird, primarily gelatinous stuff and my love of drawing,” said Bezio, who’s now working with Biology Professor Alexa Bely.

While comb jellies are distinct from the more familiar jellyfish, they are both gelatinous marine creatures whose population changes can greatly impact their ecosystems. A prehistoric iridescent mass, comb jellies come in many shapes and sizes—some as long as 5 feet—and inhabit seas worldwide. They are extremely fragile, often dissolving in preservatives within a minute’s exposure.

While comb jellies are distinct from the more familiar jellyfish, they are both gelatinous marine creatures whose population changes can greatly impact their ecosystems. A prehistoric iridescent mass, comb jellies come in many shapes and sizes—some as long as 5 feet—and inhabit seas worldwide. They are extremely fragile, often dissolving in preservatives within a minute’s exposure.

“The best way to really describe them and document their diversity and really help understand their impact on global oceanic ecosystems and trophic level impact is through photography and illustration,” Bezio added. “That way, we can document where we possibly see individual species, and because of recent advancements in genetics, we're finally able to possibly sequence them.”

Bezio’s research focuses on their systematics and re-examining the biodiversity of some of their groups.

“They are a highly underrepresented phylum due to their fragility and have the ability to drastically affect their surroundings,” Bezio said. “For example, the comb jelly Mnemiopsis leidyi almost collapsed the Black Sea fisheries market when it became invasive.”

When Bezio’s not on campus working in Bely’s lab, he’s usually in his art studio in his apartment kitchen creating illustrations with colored pencils and pens or Photoshop.

“I have a giant monitor here that's specialized for artists,” he said. “It's like a giant touch screen that you can use the stylus and draw on. And I have specialized brushes that look like actual paint strokes. I physically paint layers. I can get to, like, 300-plus layers.”

Bezio’s long-term goal is to make illustrated guides for the various marine invertebrate groups and other species that are highly scientifically accurate and easily accessible and usable for the general public.

“Science should be communicated, but much of the time the material becomes so dense that it's impossible to read,” Bezio said. “What I aim to do is communicate what's being observed to the general public.”

And jellyfish will always have a special allure for Bezio.

“These things don't have brains but have survived every mass extinction,” he said. “These animals have survived so long it gives me hope for humanity. And the deeper you go, the weirder they get. I love it.”

###

Media Relations Contact: Abby Robinson, 301-405-5845, abbyr@umd.edu

Writer: Ellen Ternes

University of Maryland

College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences

2300 Symons Hall

College Park, MD 20742

www.cmns.umd.edu

@UMDscience

About the College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences

The College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences at the University of Maryland educates more than 9,000 future scientific leaders in its undergraduate and graduate programs each year. The college's 10 departments and more than a dozen interdisciplinary research centers foster scientific discovery with annual sponsored research funding exceeding $200 million.