Biological Sciences Alum Feeds Curiosity at NASA

Astrobiologist Luoth Chou (B.S. ’13, biological sciences) believes there could be life on other planets—and if there is, she wants to find it.

When NASA’s Curiosity rover started its 254-day journey to Mars in November 2011, Luoth Chou (B.S. ’13, biological sciences) watched the televised launch from a University of Maryland dorm room. Little did she know she’d launch her own career at NASA—and work on that same rover—12 years later.

“I was watching the launch with a bunch of my friends, and I was so excited,” Chou recalled. “I didn’t know that I would get to work on Curiosity one day. At that point, I was already interested in space and maybe interested in NASA, but nobody thinks you’re going to work at NASA until you’re there.”

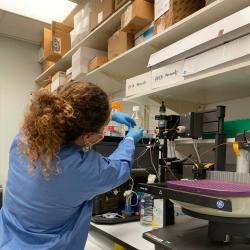

Now a research scientist with the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center’s Planetary Environments Laboratory, Chou develops instruments and designs experiments for Curiosity and other space missions destined for planets, moons, comets and asteroids across the Solar System. In this role, Chou leverages her astrobiology background to look for habitable environments—and potentially life—beyond Earth.

To improve their odds of finding signs of life, known as biosignatures, Chou builds advanced tools like mass spectrometers that can identify a complex suite of molecules in extraterrestrial environments. These sleuthing instruments have surveyed Mars and many other celestial objects, with more planned for future missions like Dragonfly, a rotorcraft expected to land on Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, in 2034.

“NASA has been sending mass spectrometers to space since the early 1970s, and our group has a footprint on almost every solar system body,” Chou said. “The only exceptions are Mercury and the ice giants, although the planetary science community is currently eyeing a mission to Uranus in the coming decade.”

For Chou, working at NASA means exploring the nature of life—an exciting question she’s been pondering for decades.

“It’s the dream job,” she said. “Getting paid to be curious—I feel like I’ve won the lottery.”

‘Everything changed’ at UMD

Born in Cambodia, Chou moved to the United States with her family when she was 11. As a curious child in a new country, she often asked deep questions about life on Earth.

“Ever since I was young, I’ve loved thinking about life: why we are here and who we are,” Chou said. “I think everyone wonders where they came from because it provides a sense of belonging, but I was more interested in the physical nature of life and how it came to be, which led me to biology.”

After graduating from high school in 2009, Chou enrolled in UMD’s undergraduate biological sciences program and took an introductory astronomy course as a “fun elective.”

“That was when everything changed,” Chou said. “After I took Astronomy 101, I thought, ‘There are all these celestial objects that we barely understand and planets in our solar system that we haven’t visited—why is it just here that has life?’”

It wasn’t long before Chou discovered the field of astrobiology and realized it held the answers to her questions—or at least the tools to start looking. At UMD, she specialized in microbiology but added an astronomy minor after taking several classes, including a planetary geology course taught by Astronomy Professor Jessica Sunshine. Chou still remembers how Sunshine went above and beyond to offer encouragement and opportunities.

“She pointed me to a few people she knew who were doing work in this field, and that extra action really stuck with me,” Chou said. “She never discouraged me from pursuing the field of astrobiology.”

After earning her bachelor’s degree in 2013, Chou enrolled in the earth and environmental sciences Ph.D. program at the University of Illinois, Chicago, where she wrote her dissertation on a group of extremophiles—organisms that thrive in extreme environments—in Antarctica’s Lake Vida.

Chou’s research revealed that Lake Vida’s bacteria live beneath more than 27 meters of ice in an extremely cold and briny environment devoid of oxygen and light. By studying Earth-based cases like these, scientists can refine their techniques for finding potential life on other planets with harsh environments.

“Antarctica is a good analog for a place like Mars, which is what I mostly study now,” Chou said. “If you go to Mars, you would want to look for a similar environment—maybe deep in the subsurface, where it’s protected from radiation and there could potentially be liquid water that supports life.”

Life on Mars?

After earning her Ph.D. in 2019, a postdoctoral fellowship at Georgetown University and NASA Goddard allowed Chou to study agnostic biosignatures—signs of life beyond some of the more obvious markers like oxygen and liquid water. The challenge with traditional biosignatures is that life on other planets might not depend on oxygen or water at all.

Considering that extraterrestrial life may have evolved to look different than Earth’s life forms, Chou said it’s important to “look for life as we don’t know it,” or identify broader molecular patterns that could indicate exotic life. Since joining NASA as a full-time research scientist in 2023, Chou has been developing next-generation tools to help identify those patterns on future space missions.

Much of her ongoing work involves developing experiments for Curiosity, which contains instruments built by Chou’s lab that characterize the chemistry of the Martian surface. While collecting data in Mars’ Gale Crater, Curiosity previously found organic molecules and traces of methane gas, which is primarily produced by living creatures on Earth. Its existence on Mars, however, remains unexplained.

While exploring Mount Sharp, a mountain within Gale Crater, Curiosity made another big discovery using a novel technique that was developed after the rover landed: the largest organic compounds ever found on Mars, including what are believed to be fragments of fatty acids—building blocks for life on Earth.

This discovery, which was publicly announced in March, offers another clue that Chou and other astrobiologists can use to find biosignatures. Chou will continue to explore the possibility of past life on Mars through missions such as ExoMars, a future European Space Agency rover set for launch around 2028.

“ExoMars is going to bring in new technology that we’re developing here at NASA Goddard,” Chou said. “The landing site is called Oxia Planum, and it’s one of the most promising locations on Mars that could potentially have environments that preserve signatures of life or signatures of habitable environments.”

For Chou, the most exciting part of her job is analyzing data from Mars just hours after it’s collected. Even if her work doesn’t yield hard proof of Martian life, every discovery—big or small—feeds her endless curiosity.

“I love the anticipation of finding something new and interesting,” Chou said. “And even if it’s not interesting, it helps add that extra data point to our equation of what Mars is like and whether it was habitable. As long as we’re closer to finding life today than we were yesterday, I’m happy.”