UMD Astronomer Helps Take a Closer Look at ‘Dinky’ Asteroid

As a member of NASA’s Lucy Team, Jessica Sunshine will study distant asteroids that may hold clues to how our solar system formed.

In 1974, anthropologists discovered a fossilized skeleton of a hominid (Australopithecus afarensis, a pre-human ancestor) in Ethiopia that they nicknamed “Lucy.” The Lucy fossil provided scientists with crucial information about our biological predecessors and unique insights into human evolution that continue to shape how we view our origins today.

Now, almost 50 years later, a team of astronomers hopes to do the same with our understanding of planetary formation and evolution.

Named after the Lucy fossil, NASA’s Lucy mission will study the Jupiter Trojan asteroids, a never-before-explored group of small bodies consisting of materials left over from the formation of the solar system’s biggest planets. The team, which includes University of Maryland Professor of Astronomy and Geology Jessica Sunshine, plans to track these asteroids and obtain data about their appearance, temperature and composition. The Lucy spacecraft will collect its observations from a distance as it speeds past each of these celestial bodies.

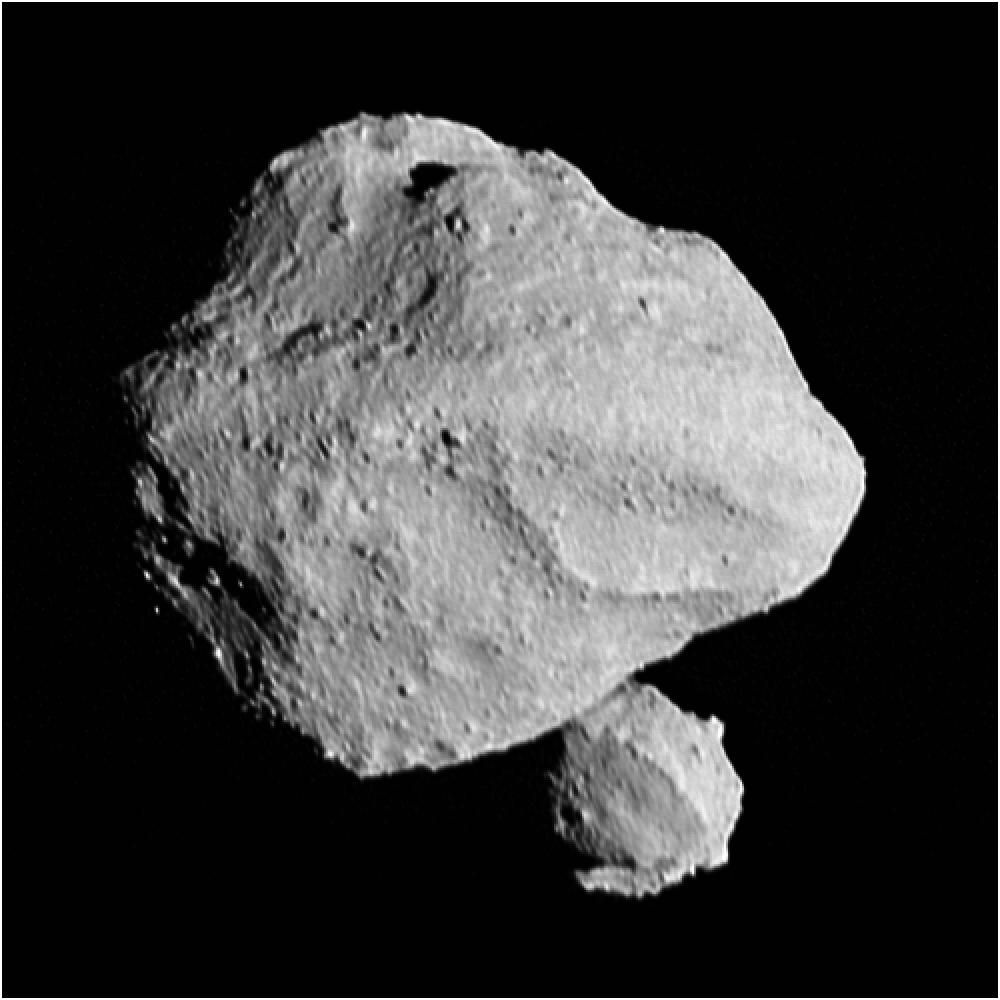

On November 1, 2023, the Lucy team completed its first test run, flying past an asteroid called Dinkinesh (the Ethiopian name for the fossil). “Dinky” —for short—is the smallest asteroid located in the main belt ever studied by spacecraft. The main asteroid belt spans the space between the orbits of Jupiter and Mars around the sun, making it one of the innermost rings of cosmic material in our solar system. Dinky’s location is one reason the Lucy team selected the tiny asteroid as a target for its first test run. Like a celestial time capsule, Dinky opens a window to the solar system’s past and helps inform theories about Earth’s formation.

“Dinkinesh is less than a mile wide, but there is a lot to learn from such a small asteroid. It’s a piece of a much bigger history,” said Sunshine, who is also director of the Small Bodies Group at UMD. “We can use our observations to draw connections between main belt asteroids like Dinkinesh and near-Earth objects. Studying it gives us insight into where Earth came from and how the planet came to be.”

Surprise discoveries: ‘A three for one deal’

The Dinkinesh flyby allowed the team to take a peek at the diminutive asteroid’s surroundings, which had only been visible as an “unresolved smudge in the best telescopes” since 1999, the year of its initial discovery. With specialized instruments and cameras on the Lucy spacecraft, the team found that Dinky had a satellite in its orbit—but something was odd about it.

“We were extremely surprised to discover that Dinkinesh appears to have not just one but two moons in its orbit,” Sunshine said. “In that way, this was bonus science since we were expecting only one asteroid but found three. Our flyby was a three-for-one deal.”

Dinkinesh’s two satellites are collectively called a contact binary, meaning two smaller celestial objects that have gravitated toward each other until they touch. Although contact binaries themselves are not uncommon, the team was puzzled to see two similarly sized moons. Generally, a bigger object would have a stronger gravitational pull and draw smaller objects closer. For the team, the nearly identical size and shape of the two Dinky moons presented an intriguing mystery.

“We have to study smaller bodies to understand how to build a big body like Jupiter or Earth,” Sunshine explained. “These two different bodies somehow came together and over time began to fuse into one, and we’re catching it now at this stage. We don’t know for sure, but we think that the primary asteroid Dinkinesh likely started spinning and that this material came off to become these satellites and are now fusing back together.”

The Lucy spacecraft will continue its journey across space to capture data from asteroids for the next 12 years. Its next target is DonaldJohanson, an asteroid named after the paleontologist who discovered the fossilized hominid Lucy in 1974. The NASA Lucy team expects the spacecraft to encounter DonaldJohanson in 2025 before it travels to the eight Jupiter Trojan asteroids.

“This is just the start of our work here,” Sunshine said. “Dinkinesh was our first flyby with six more to come so it gave us the chance to test out our instruments and refine our ability to collect data. We happened to discover a lot of unanticipated findings on this first stop, including the mystery of the Dinkinesh contact binary. Looking forward, there’s likely to be even more unexpected objects of interest out there and more questions to think about.”