Young Scientists, Ancient Discoveries

Across the nation, elementary, middle and high school students are experiencing the thrill of discovering shark teeth fossils that are tens of millions of years old—and of receiving credit for their work in scientific journals. The students' experience is courtesy of SharkFinder, a citizen science project led by University of Maryland Entomology Instructor Bretton Kent and sponsored by Paleo Quest, a nonprofit that advances the science of paleontology.

One such student scientist is seven-year-old David, of Bethesda, Md., a young fossil lover who discovered SharkFinder during the 2014 USA Science & Engineering Festival in Washington, D.C. After watching David investigate sample kits at the event, Kent personally invited the boy to work in his lab.

On Thursdays during his summer break, David's mother drove him to College Park to sort fossils in Kent's laboratory. There, David says he searched for rock samples with "especially hard surfaces, serrated edges or curiously shaped holes," all of which could suggest evidence of an ancient sea creature. During his first two weeks in the lab, he found possible fossils of worm tunnels, ray plates and shark teeth.

"It's not every day that you can find a shark tooth!" exclaims David, who credits SharkFinder with giving him new opportunities to fossil hunt.

Fossil samples are collected by Paleo Quest staff from sites in Virginia and Maryland, including the Calvert Formation, part of Calvert Cliffs State Park in southern Maryland. Calvert Cliffs is famous for fossils from the early Miocene period, between 20 and 10 million years ago. Staff send the sediment samples, along with tweezers and magnifying glasses, to students across the country. The students, with the aid of fossil photographs, identify potential fossils and mail them to Kent's laboratory.

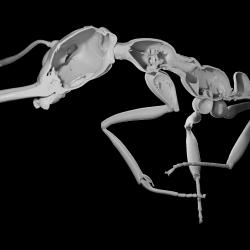

In Kent's lab, undergraduate students sort through the samples, many of which are too worn or damaged to confirm as fossils. Because the shark teeth are so tiny—often no more than one or two millimeters—Kent's students use a state-of-the-art dissecting microscope to visually determine the species of origin for intact specimens. Identified fossils are curated and displayed at the Calvert Marine Museum in Solomons, Md.

Since SharkFinder efforts began two years ago, student participants have found more than 25,000 fossilized teeth. Kent's group is currently preparing nine research papers on recent findings, all of which will credit the K-12 students who contributed fossils or photographs.

A lack of information on shark species' fossils in Maryland led Kent to launch the program. Though he knew the Calvert Cliffs area potentially contained tens of thousands of fossil samples, he did not have enough time or manpower to excavate and identify them himself. An experienced citizen science organizer—SharkFinder is his third such project—Kent believed this project was a prime opportunity to involve the public in science, engage students in research and gather new paleontological data. Kent decided to collaborate with Paleo Quest, an organization dedicated to advancing the state of education, exploration and contributions in paleontology and geology.

"After I teamed with Paleo Quest, our biggest challenge was figuring out how to organize and transport the sheer volume of material from Calvert Cliffs to classrooms across the country and then back to the lab," explains Kent, noting that tens of thousands of schools across the nation now participate in the program. He is eager to add even more schools to that list.

The group's goals include developing new tools to train current teachers and students in identifying the species of origin of fossils. "We hope to show students how science is done by giving them the chance to participate in the real thing," adds Kent.

Although the majority of the young shark finders are not applying to college or jobs yet, Kent anticipates the program will inspire students to pursue paleontology research careers.

David, though, needs no further convincing. "I hope that SharkFinder will be the start of my career in fossil hunting," he says.

Writer: Irene Ying