Hard Work, Teamwork and Fairness

Willie E. May (Ph.D. ’77, chemistry) brings 50-plus years of research and administrative leadership experience to his new role as AAAS president-elect.

When Willie May (Ph.D. ’77, chemistry) was a graduate student at the University of Maryland, he got his first taste of just how far his passion for science and his determination to succeed could take him. Not only was he earning his Ph.D. in chemistry—something he never would have imagined as a kid growing up in Alabama—he was also making regular 3,000-mile treks from College Park to a remote research site in Prince William Sound, Alaska, part of his full-time job conducting liquid chromatographic studies for the federal agency now known as NIST—the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

"While I was in graduate school, I was part of a team doing the baseline pollution assessment of the naturally occurring levels of petroleum hydrocarbons in southern Alaska prior to the completion of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline,” May recalled. “Here I was, a mere 20-something-year-old kid having a chance to do something no one had ever done before, and it was so much fun. I learned through that experience the value of hard work and not to shy away from what might initially appear to be a herculean challenge.”

Those years would set the stage for May’s lifelong relationship with UMD and a 45-year career at NIST. He rose from his first job as an analytical chemist all the way to NIST director and U.S. Under Secretary of Commerce for Standards and Technology, making a major impact as “the government’s top scientist.” In 2017, he returned to familiar territory as the director of major research and training initiatives at UMD’s College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences. In 2018, he joined Morgan State University, Maryland’s largest historically black university, as vice president for research and economic development. Now he’s taking on his latest challenge: in March 2023, the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) welcomed May as their newest president-elect.

“It’s clear to me that I’m exactly where I should be at this point in my life,” he said, in reference to his being at Morgan (an HBCU) and taking on his new AAAS responsibility.

For May, the role of president-elect offers a new platform to address the challenges facing the nation’s scientific community and to advance his own personal commitment to fairness and diversity.

“For us to stay competitive as a nation, certainly it is fair to incorporate and involve underrepresented minorities,” May explained. “But let’s put fairness aside for a minute—it’s also in our national competitive best interest; we lose as a nation if we don’t cultivate and utilize all of our country’s assets.”

Learning life lessons

May was raised in the public housing projects of Birmingham, Alabama, in the 1950s and quickly learned to adapt to the challenging conditions around him.

“Growing up in Birmingham in the 1950s and 1960s was about like you may have imagined with the deprivation and the segregation. There were a lot of poor people crowded into a very small space, so you had to learn to get along with a wide variety of personality types just to survive,” he said.

There were also the detriments of being forced to live in a totally segregated environment.

“I remember thinking, if I am ever in a position of responsibility, and had no reason to think that I ever would—I’ll go out of my way to be fair to everyone because I could see every day the impact of unfairness on people’s lives,” he said.

May’s experiences growing up taught him important lessons about life, from the classroom to the baseball field.

“I got good grades in school because it made my mother happy, then I got my butt beat about it because academics was not something that was largely revered in the community. But because athletics was respected, I learned to do both,” May explained. “My experiences taught me how to see the big picture, and I wouldn’t trade that for anything in the world.”

In high school, May made his first connection with chemistry.

“My high school chemistry teacher took me and a few other students aside and taught us college chemistry courses,” May recalled. “He would go away to Alabama A&M in the summer and when he came back, he would teach us what he had learned. Eventually, I realized I didn’t want to work in the steel mills or the coal mines, I wanted to wear a white lab coat—I thought chemistry was cool.”

Meanwhile, May continued playing baseball. And it seems fitting that he even crossed paths with his famous almost-namesake.

“Willie Mays, who is also from Birmingham, played minor league baseball with our high school baseball coach Cap Brown. During the early ’60s, the Giants were not winning many pennants and he would always be in town in late September. He would hang out with Coach while we were having fall baseball practice,” May recalled. “Coach would say things like ‘Willie, you see that skinny blank-blank guy out there in center field? He’s probably faster than you were but he’s got a popsicle arm, can’t hit the curve ball worth blank! But I still like him and he finds ways to make his teams win.’”

By the time May received his bachelor’s degree from Knoxville College in Tennessee in 1968, he was on track toward a career in chemistry. Although he had three fellowships to pursue graduate work, he initially took a position with the Atomic Energy Commission in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. He later landed a temporary position at NIST, and with it, a research assignment doing those pollution studies in southern Alaska prior to the completion of the Trans-Alaska pipeline. He also entered graduate school at Maryland. That experience sparked a love of scientific discovery and showed May how his work as a chemist could make a difference.

“We didn’t know it then, but our data would be used later to do the damage assessment when the Exxon Valdez went aground years later,” May explained. “Having a chance to do something that revolutionary was definitely exciting.”

And the challenges for May at NIST just kept getting bigger and better. A recipient of dozens of national and international awards, May led NIST's chemistry-related research and measurement programs for more than two decades and traveled to more than 50 countries. His personal research in trace organic analytical chemistry and chemical properties of organic compounds has been described in more than 100 peer-reviewed publications.

“I worked in every level of the organization and every job I had I thought I’d be happy doing it for the rest of my life,” May explained. “NIST really made me who I am and gave me opportunities that I did not know existed, like being vice president of the International Committee for Weights and Measures that sets the global standards for the same.”

Paying it forward

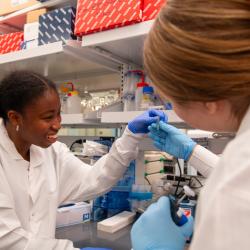

During his years at NIST and in his later role as director of major research and training initiatives at UMD, May made it a priority to pay his own success forward, promoting innovation, supporting Black scientists and working to create scholarship programs in science for underrepresented students at the undergraduate and graduate levels.

“Honestly, I think it’s my responsibility to respect, mentor, try to provide opportunities and certainly provide some steering to young African Americans,” May said. “I’ve been blessed with so many opportunities, this one-in-a-million, improbable journey from the projects in Birmingham to the director at NIST and beyond, so I know I have that responsibility.”

May’s connection to UMD is still as strong as ever. He still makes regular visits to campus, both his kids are Maryland alums and he’s been a proud season ticket holder for Terps basketball for more than 20 years.

“My time at and association with College Park has changed my life,” May reflected. “I will always be a Terp.”

Now, looking ahead to his role as president-elect of AAAS, May hopes he can help advance U.S. science and technology toward a more competitive—and more inclusive—future.

“When I was in elementary school, the Russians launched Sputnik. The U.S. had to catch up and lots of money was provided to support science and engineering. During those times, being a scientist was cool, but now we’re going through a time when we have to realize that science and technology are our national salvation,” May said. “It is so crucial for the U.S. to be competitive in this area, and certainly at this point in our nation’s history we need all able minds and bodies on board and contributing.”

For May, that mission couldn’t be more important. And after more than 50 years, he’s still excited about science and technology and still gets up every morning looking for new challenges and eager to mold young scientific minds.

“After all these years, I’m still working and I plan to work as long as I can,” May explained. “I would like to do as much as I possibly can to make this a better world and fairer world as well.”