UMD Students Name Asteroid ‘Diamondback’

Students in the ASTR 315: Astronomy in Practice class measured the asteroid’s light curve and rotation period, then gave it a Terp-inspired rebrand.

Twenty-five years after an automated space survey discovered an asteroid between Mars and Jupiter, that astronomical object finally got a name: Diamondback.

Two teams of University of Maryland students in the ASTR 315: Astronomy in Practice class orchestrated this Terp-inspired rebrand during the spring 2025 semester. After measuring the asteroid’s light curve and rotation period, the students petitioned the International Astronomical Union (IAU) to name the object—which previously went by a string of numbers and letters—after UMD’s mascot, the diamondback terrapin.

The IAU accepted the new name in July, and the students’ observations appeared in the journal The Minor Planet Bulletin on September 22, 2025. This is the second time that ASTR 315 students named a celestial object—students named a different asteroid “Testudo” during the spring 2024 semester.

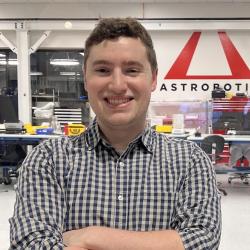

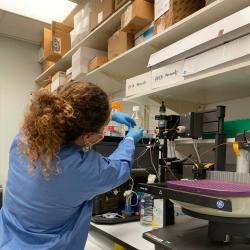

Two of the students who studied the Diamondback asteroid, finance master’s student Zahra Schenck (B.S. ’25, economics) and biological sciences major Benjamin Weintraub, came up with the UMD-themed name and the rationale for the asteroid’s new designation.

“‘Diamondback’ honors our mascot and connects with students who read The Diamondback newspaper,” Schenck explained. “The name felt like a tribute not only to both of our teams, but also to the entire ASTR 315 class and all the classes before us that studied other asteroids. Plus, now I have a great fun fact to share during icebreakers.”

Astronomy Principal Lecturer Melissa Hayes-Gehrke, who teaches ASTR 315, said the class gives non-astronomy students the tools and autonomy to make scientific discoveries. Even if students are not naming an astronomical object, they still collect data and publish their results in a peer-reviewed journal.

“The fact that students are responsible for the data is a big deal, and it’s important to them,” Hayes-Gehrke said. “They’re publishing something new, and they’re excited to be doing real science.”

Typically, the person who discovers an asteroid secures the naming rights, but not everyone seizes that opportunity. Increasingly, asteroids are also being discovered through automated space surveillance programs, leaving plenty of unnamed objects to choose from.

For her class assignments, Hayes-Gehrke doesn’t go looking for unnamed asteroids, but instead chooses objects with high visibility, making them easier to observe—in theory, at least. Her students used the iTelescope in Australia to collect data remotely on Diamondback, and while unfavorable weather conditions and software glitches sometimes complicated matters, the experience taught Schenck and her classmates important lessons in patience and persistence.

“The astronomical software had a steep learning curve, and there were plenty of small hiccups throughout the project,” Schenck said. “That included delays in observations and working with the asteroid's original name, 2000 OS51. Things did not always go according to plan, but learning how to stay patient and adapt is a skill that applies in any field.”

The class will be taught again next spring, thanks to a grant Hayes-Gehrke received from the Maryland Space Grant Consortium to help cover the cost of iTelescope for ASTR 315 students. Ultimately, Hayes-Gehrke hopes that students leave her class with a better appreciation of astronomy and the scientific process.

“Students find out firsthand that science is not a straight-line process, that things don't always happen correctly the first time, and that there's a lot of redoing and revision that goes into it,” Hayes-Gehrke said.

Though Schenck said she was “not especially interested in astronomy” before taking the ASTR 315 class, she ended the semester with a greater appreciation for the complexity involved.

“I knew we would be studying asteroids, but I still thought most astronomy involved people looking through telescopes,” she said. “I did not realize how much it involves data, software and collaboration. This made it a lot more engaging than I expected.”