UMD Entomologist Bretton Kent Helped Smithsonian Reconstruct a Life-size Prehistoric Shark

Fossil remains and scientific deduction ensured an accurate 52-foot model of a hungry megalodon greets diners in museum café

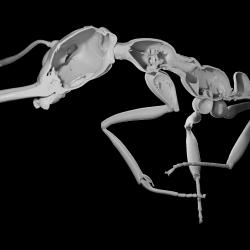

Constructing a model of an animal that went extinct well before humans walked the Earth takes a little imagination and a lot of scientific expertise. So, when the team at Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History had to design a life-size model of Carcharocles megalodon, the largest predatory fish to ever swim in the ocean, it turned to Bretton Kent, an instructor in the University of Maryland Department of Entomology.

Kent was asked to join the design team, which was led by Hans Sues, chair of the museum’s Department of Paleobiology, because Kent is an authority on the fossils of the Chesapeake Bay region. The region is one of the richest areas for fossils of megalodon—a giant shark that lived between 3.6 and 20 million years ago. He wrote about the scientific evidence for megalodon’s physical description in the Smithsonian’s 2018 book titled “The Geology and Vertebrate Paleontology of Calvert Cliffs, Maryland, USA.”

The life-size model of megalodon Kent helped design is a new feature of the museum’s renovated café that is meant to evoke the thrilling experience of visiting the David H. Koch Hall of Fossils-Deep Time. This reimagining of the museum’s dinosaur hall is scheduled to open on June 8, 2019.

Visitors to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History can now enjoy their lunch while pondering, at eye level, the razor-sharp teeth and wide-open maw of the 52-foot-long prehistoric shark. We asked Kent a few questions about designing the model.

How do scientists know what megalodon looked like?

There are no complete megalodon skeletons. Most of what is known about them comes from fossil teeth and bite marks on the bones of other marine animals such as whales. With so little to go on, scientists make inferences based on related species and the relationships between form and function that would govern the appearance of such a large shark.

Megalodon fossils have been found throughout the world and in deep-sea sediments, suggesting that the shark lived an oceanic lifestyle. From living sharks, we know that most oceanic species evolved a distinct body shape—influenced by physics and biomechanics—that is most efficient for swimming long distances. Based on megalodon’s lifestyle and the function-driven forms of other ocean-dwelling sharks, we can infer its body shape as well as the relative size and placement of its fins.

What questions did the team need to answer to create the model?

The most speculative aspect of the reconstruction was the body color. For a large, open-ocean shark like megalodon, we would have every reason to expect that the body would exhibit countershading—in this case, a dark back and a white belly. This is an almost universal color scheme for large open-ocean fishes, because it helps them avoid detection. When they’re swimming below other fish, a dark back helps them blend in with the darkness below. When swimming above other fish, the white belly stands out less against sunlight or moonlight shining down through the surface of the water.

When the team was designing the megalodon model for the museum, the question was: What color is “dark” for the back? In modern open-water sharks, this can range from shades of gray and blue to brown or even purple. We have no way of knowing which is most appropriate for megalodon. We chose dusky brown, which is as reasonable as any.

What are the most fascinating unanswered questions about megalodon?

One of the biggest questions may be whether it was a predator at all. Megalodon’s extreme size introduces some interesting issues regarding potential physiological constraints. For one thing, greater size puts greater demands on an animal’s circulatory system. Predatory fishes require a circulatory system that can support speed and bursts of energy.

Large predatory fishes also require adequate blood supply and warmth to portions of the brain that enable the fish to identify, track and accurately strike vulnerable areas of a prey animal’s body. There may be limits to the size of large predators due to these circulatory needs. The largest predatory fish living today is the great white shark, which is believed to be a distant relative of megalodon. Great whites are known to reach 23 feet in length, which is less than half of megalodon’s 50 to 60 feet.

Today, the only fishes that come close to megalodon’s length are slow-moving, docile filter feeders such as whale sharks and basking sharks, which are known to reach around 40 feet in length. With its large triangular cutting teeth, we know megalodon was not a filter feeder. But some scientists have suggested that it wasn’t a fast-moving, agile predator either.

Rather, it may have been a scavenger that used its extreme size to intimidate other scavenging fishes away from a meal. This isn’t a widely held belief. And there is some evidence from bite marks on fossil whale bones to suggest megalodon was, indeed, a predator that killed live prey. But without more fossil evidence, we won’t be able to say for certain.

###

Writer: Kimbra Cutlip

Media Relations Contact: Abby Robinson, 301-405-5845, abbyr@umd.edu

University of Maryland

College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences

2300 Symons Hall

College Park, Md. 20742

www.cmns.umd.edu

@UMDscience

About the College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences

The College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences at the University of Maryland educates more than 9,000 future scientific leaders in its undergraduate and graduate programs each year. The college's 10 departments and more than a dozen interdisciplinary research centers foster scientific discovery with annual sponsored research funding exceeding $175 million.