Can’t Stand Gossip? New Research Suggests That Gabbing About Others Is ‘Not Always a Bad Thing’

Gossiping offers unexpected benefits beyond idle chitchat, according to a study conducted by UMD and Stanford researchers.

Rumormongers, blabbermouths, busybodies—no matter what you call them, gossipers get a bad rap. But new theoretical research conducted by University of Maryland and Stanford University researchers argues that gossipers aren’t all that bad. In fact, they might even be good for social circles.

Gossiping—defined as the exchange of personal information about absent third parties—can provide a “social benefit,” according to the researchers. Their study revealed that gossip is good at disseminating information about people’s reputations, which can help recipients of these tips connect with cooperative people while avoiding selfish ones.

“When people are interested in knowing if someone is a good person to interact with, if they can get information from gossiping—assuming the information is honest—that can be a very useful thing to have,” said study co-author Dana Nau, a retired professor in UMD’s Department of Computer Science and Institute for Systems Research.

In their study published February 20, 2024, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers used a computer simulation to help solve a long-standing mystery in social psychology: How did gossiping evolve into such a popular pastime that transcends gender, age, culture and socioeconomic background?

“One previous study shows that, on average, a person spends an hour per day talking about others, so this takes a lot of time out of our daily life,” said the study’s first author Xinyue Pan (M.S. ’21, Ph.D. ’23, psychology), who published part of this research in her master’s thesis. “That’s why it's important to study it."

Previous theories suggested that gossip can bond large groups of people and foster cooperation, but it was unclear what individual gossipers would gain from these interactions.

“This has been a real puzzle,” said study co-author Michele Gelfand, a professor at Stanford Business School and a professor emeritus in UMD’s Department of Psychology. “It’s unclear why gossiping, which requires considerable time and energy, evolved as an adaptive strategy at all.”

Why gossip recipients were so willing to lend a sympathetic ear to gossipers or behave differently in their presence also remained unexplained.

To better understand the complex webs of gossip, the research team used an evolutionary game theory model that mimics human decision-making. By combining tenets of evolutionary biology and game theory, the researchers could watch how their agents, or virtual study subjects, interacted with each other and altered their strategies to receive rewards.

In this case, the researchers wanted to find out whether agents would use gossip to protect themselves or to exploit others. Agents could cooperate with gossipers or defect; they could become gossipers themselves; and they could change their strategies after observing the consequences or rewards of other agents’ decisions. By the end of the simulation, 90% of the agents had become gossipers.

The researchers argued that people are more likely to cooperate in the presence of a known gossiper because they want to protect their own reputation and avoid falling victim to the rumor mill. For gossipers, receiving another person’s cooperation can be a reward in itself.

“If other people are going to be on their best behavior because they know that you gossip, then they're more likely to cooperate with you on things,” Nau explained. “The fact that you gossip ends up providing a benefit to you as a gossiper. That then inspires others to gossip because they can see that it provides a reward.”

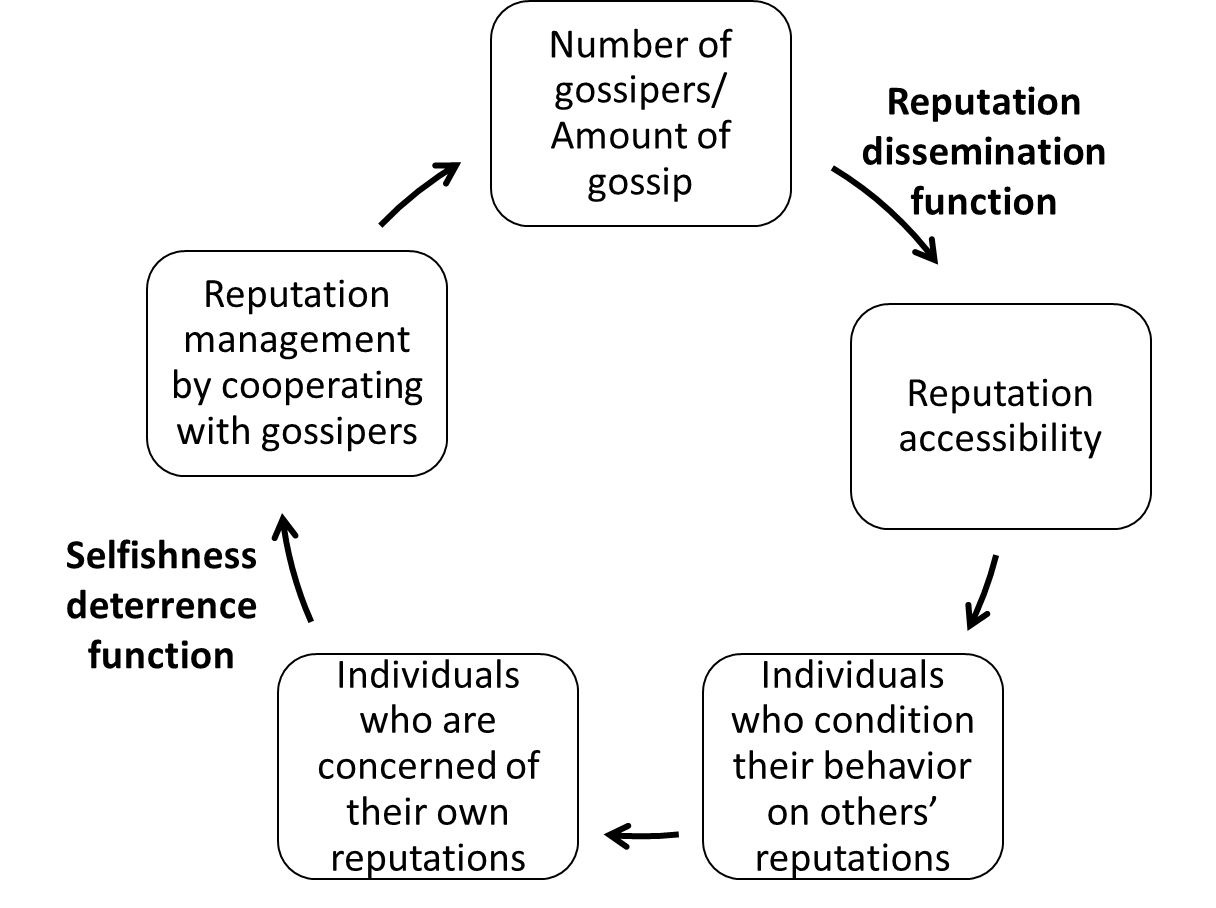

The researchers argue that gossip proliferates because sharing information about people’s reputations can have a “selfishness deterrence” effect on gossip recipients. In other words, gossip recipients condition their behavior on others’ reputations, and because they don’t want to be the subject of future gossip, this deters them from acting selfishly. Thanks to their ability to influence the behavior of others and encourage cooperation, gossipers have an “evolutionary advantage” that perpetuates the cycle of gossip and provides a useful service to listeners.

Though gossip has a negative connotation, Pan stressed that the information gossipers share can be complimentary. Regardless of its content, gossip has a useful function.

“Positive and negative gossip are both important because gossip plays an important role in sharing information about people’s reputations,” said Pan, who is now an assistant professor at The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen. “Once people have this information, cooperative people can find other good people to cooperate with, and this is actually beneficial for the group. So gossiping is not always a bad thing. It can be a positive thing.”

Their simulation also considered different factors that help or hinder the spread of gossip, ultimately confirming what past research has shown: Small-town gossipers aren’t just a movie trope.

“The model highlights contexts in which we can expect more gossipers to evolve, particularly when social networks have high connectivity and mobility is low, consistent with research on rural areas,” Gelfand said. “It gives clues to contexts where gossiping may be more or less likely to flourish.”

Nau explained that their research does not encompass the full scope of human complexity nor can it replace behavioral studies. However, computer simulations can yield new theories that inspire follow-up research involving human subjects.

“People are very complicated and we can’t come up with a simulation that does everything that people do, nor would we want to,” Nau said. “Since it’s an oversimplification, you can’t say conclusively that this is how people behave, but you can develop insights. Those can then lead to scientific hypotheses that you can try to investigate through studies that involve human participants.”

The researchers hope to pursue a follow-up study to test one of their simulation’s predictions on human participants: the idea that gossip is effective when people don’t have other methods of gathering information about people’s reputations.

“That, for me, is one of the really exciting parts of this,” Nau said. “If we can come up with hypotheses and verify the predictions of those models on human studies, then that’s what makes this kind of thing useful.”

There is one thing the researchers can already say with confidence: Based on the overwhelming number of gossipers in their simulation and in real life, gossiping is unlikely to go away anytime soon.

###

In addition to Nau, Pan and Gelfand, this study was co-authored by Vincent Hsiao (B.S. ’18, computer science; B.S. ’18, mathematics; Ph.D. ’24, computer science), a research scientist at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory.

Their paper, “Explaining the evolution of gossip,” was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on February 20, 2024.

This research was supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (Grant No. 1010GWA357). This article does not necessarily reflect the views of this organization.