Choosing Trees to Cool Cities Wisely

Confronting Climate Change

We see the signs everywhere—our planet’s future is in jeopardy. As global temperatures rise, greenhouse gases reach record levels and extreme weather events strike more frequently, we must ask the question: What will it take to solve the grand challenge of climate change?

Researchers in the University of Maryland’s College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences (CMNS) are fiercely committed to the fight against global warming. These scientists are tapping into satellite data to predict crop-killing droughts before they happen, identifying trees that adapt to climate change instead of worsening it, and unraveling the complex relationship between airborne pollutants and weather conditions. Grand challenges demand bold ideas and real-world solutions. In CMNS, we lead Fearlessly Forward.

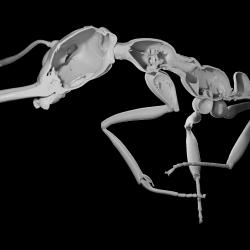

Karin Burghardt wants to make sure they’re choosing their tools wisely. Specifically, she studies how cities can select the right trees to plant as part of their strategy to adapt to climate change—because planting the wrong ones could make the effects of climate change worse.

“We need to understand how the tree species we select today might affect the health of the city’s entire tree canopy 40 years down the line,” said Burghardt, an assistant professor of entomology.

Urban areas absorb heat more than rural spaces and can be 7 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than surrounding landscapes, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. To combat this “heat island” effect, city managers plant shade trees to cool buildings and streets, reduce energy use, absorb runoff from severe storms and help capture greenhouse gases. But they often don’t think much about the potential consequences of the trees they choose.

“People have selected trees for city planting based on particular traits they like, such as purple leaves or a lot of flowers or fall leaf color,” Burghardt explained. “But these trees may come from areas with very different climates, and they may not actually have traits that allow them to be adapted to urban stressors, like high temperatures or pest outbreaks, which are expected to increase as a result of climate change.”

Burghardt collaborates with researchers from Johns Hopkins University and the U.S. Forest Service to understand how the genetic traits of different street trees in Baltimore might affect the trees’ ability to resist pests and higher temperatures.

“We have to think about the lag time, because after planting trees, you’re waiting 30, 40 years before really getting the full benefits of that tree,” Burghardt said. “And selecting for traits that aren’t related to resilience to climate change may have undesired consequences.”

Part of the team’s concern is that trees planted today won’t survive climatic conditions of the future, but perhaps more important is the impact cultivated street trees may have on the fragments of wild forest within cities. Those fragments are critical buffers against rising temperatures and increased flooding, and they provide vital habitat and migratory pathways for wildlife.

“Pollen from street trees could potentially fertilize wild trees in the forest fragments,” Burghardt said. “If they do, the question is, will they be adding traits that are less suited to those forest environments, especially with the climate conditions we expect 30 or 40 years from now?”

With funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Burghardt and her colleagues sample maple trees in Baltimore streets, parks and yards to understand how genes could be moving through different populations that make up the city’s tree canopy.

“If we’re introducing traits from tree varieties that are really poor at dealing with the climate conditions coming down the road, then we might not only be losing our street trees in the future, we could actually be losing the canopy from wild forest fragments as well,” she said.

Burghardt hopes that arming city managers and planners with this information will help them select the trees to get the job done properly and without unintended consequences.

Written by Kimbra Cutlip

This article was published in the Summer 2022 issue of Odyssey magazine. To read other stories from that issue, please visit go.umd.edu/odyssey.

Also from this issue: