A Bedrock Gift for Geology Seniors

Stifel, an associate professor emeritus, created the department's undergraduate senior thesis program, which continues today more than 20 years after his retirement to Maryland's Eastern Shore. Now a dedicated environmentalist, Stifel pledged $250,000 to sustain UMD's geology senior thesis program in perpetuity—as a way to encourage student exploration and to better understand our world. "Geologists are basically detectives," Stifel said. "They see evidence for things that happened in the past, and they have to figure out the circumstances that allowed this specific evidence to evolve."

Take Stifel's life, for example. His own career evolved unexpectedly. Stifel left West Virginia for prep school at the Hill School in Pennsylvania, which then led him to Cornell University where he majored in geology.

He was accepted to the University of Utah to pursue a master's degree. But having completed a voluntary thesis at Cornell, he was so well prepared that he received high marks and instead earned a doctorate in geology and zoology.

In 1966, Stifel arrived at UMD—one of the first three instructors in a geology program that was then housed in the agronomy department. Lab hours were limited because the building was locked up for the night, and Stifel recalls propping windows open so undergrads could sneak in after hours to conduct research.

As the university reorganized its departments and schools in 1973, geology faculty members saw an opportunity to create their own major. From the earliest days, Stifel insisted that undergraduates be required to design, complete and defend a research project.

"My main contribution was insisting that the course be as good for any one student as it was for another, whether that student was going to stock shelves at Safeway or going on to Harvard for graduate school," Stifel recalled. "A lot of times, character building was as important as the facts learned."

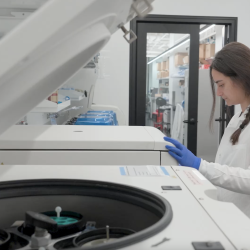

The thesis program quickly evolved from a one-credit class to its current format as a yearlong, six-credit program. In the first semester, students select a research question, determine what resources they need and test their data to prove the work is feasible. In the second semester, students complete the research, write a thesis and defend it in front of as many as 100 fellow students and faculty members.

Stifel still often attends the presentations, eager to see how students have focused their research lenses. Projects have taken the students to construction sites in Washington, D.C., rock outcrops in western Maryland, and as far away as Alaska and Africa.

One of the biggest challenges is managing student expectations.

"We can find out what was happening 400 million years ago by sampling and observation," Stifel said. "But you have to limit the students sometimes. They want to solve all the world's problems."

Stifel said what the students study is less important than learning how to collect and analyze data properly. The students also learn to troubleshoot, such as finding another streambed to sample when the original one remained icebound midway through the second semester.

Many students say their thesis projects became the foundation of successful careers, according to Philip Piccoli, a senior research scientist in the Department of Geology who oversees the thesis program today. While more departments at UMD are starting undergraduate thesis programs, many of those remain voluntary. That's also true of geology tracks at other universities—a fact that helps set Maryland apart. "For many of our students, this is a transformative experience. They're taking what they've learned in the lab and applying it to research," Piccoli said. "These aren't pet projects our faculty have. The students take ownership in this."

Keeping students motivated with a mix of fun and rigor harkens back to Stifel's classroom philosophy.

In his teaching days, Stifel would conclude a unit on molluscan paleoecology with a classroom feast of cherrystone clams, mussels and oysters. He was famous for his Hope House stomps, inviting dozens of students and faculty members to his historic farm on the shore of Woodland Creek in Talbot County, Maryland. There, they could discuss their common bonds as geologists and admire the wildlife and scenery that made Stifel a devoted environmentalist.

"Pete was the first teacher in my life who knew about and loved fossils as much as I do," recalled Lawrence Thrasher, B.S. '75, geology, a Bureau of Land Management geologist.

Stifel advised Thrasher on his senior thesis that was built around a collection of fossils Thrasher found in northern Virginia as a child. The Paleozoic invertebrates—mostly corals and brachiopods—washed down to the D.C. area in streambeds from West Virginia and ended up as local gravel deposits.

"That was great preparation for my master's thesis several years later at the University of North Dakota on the invertebrate fossils—mostly brachiopods—and biostratigraphy [layers used to help date rocks] of the now-famous Bakken Formation," Thrasher said. "And that was all a great background for my current position as a federal geologist."

Thrasher still recalls cracking open chert, or sedimentary rock, with Stifel to reveal the seashells, and he especially remembers the inspiration both men found in that process.

"Field work is the great equalizer," Piccoli said. "When you're at a site swinging a sledge hammer or trying to take notes in pouring rain and it's 35 degrees, you're all at the same level."

Some students work from laboratory slides or existing samples, if travel is prohibitively expensive. In the past, thesis expenses have been borne by the students themselves or by faculty advisors—even when the student's work didn't support the advisor's own line of research.

Stifel's gift will allow students to learn how to write grants, make travel to field sites more practical and enable more students to attend geology conferences. As a result, students will find themselves better positioned for graduate school or the job market.

"The inquiry-based learning that is fundamental to the senior thesis transcends traditional brick-and-mortar learning. This method allowed me to do science, which I found far more exciting than regurgitating science on exams," said Adam Simon, B.S. '95, Ph.D. '03, geology, an associate professor at the University of Michigan who researched copper in the Tuolumne Intrusive Suite for his senior thesis. "I would not be where I am today without my senior thesis experience."

Written by Kimberly Marselas

This article was published in the Winter 2019 issue of Odyssey magazine. To read other stories from that issue, please visit go.umd.edu/odyssey.