New Discovery Offers a Glimpse of Our Solar System’s Potential Fate when the Sun Dies

A team including UMD astronomers found a Jupiter-like planet orbiting a white dwarf star

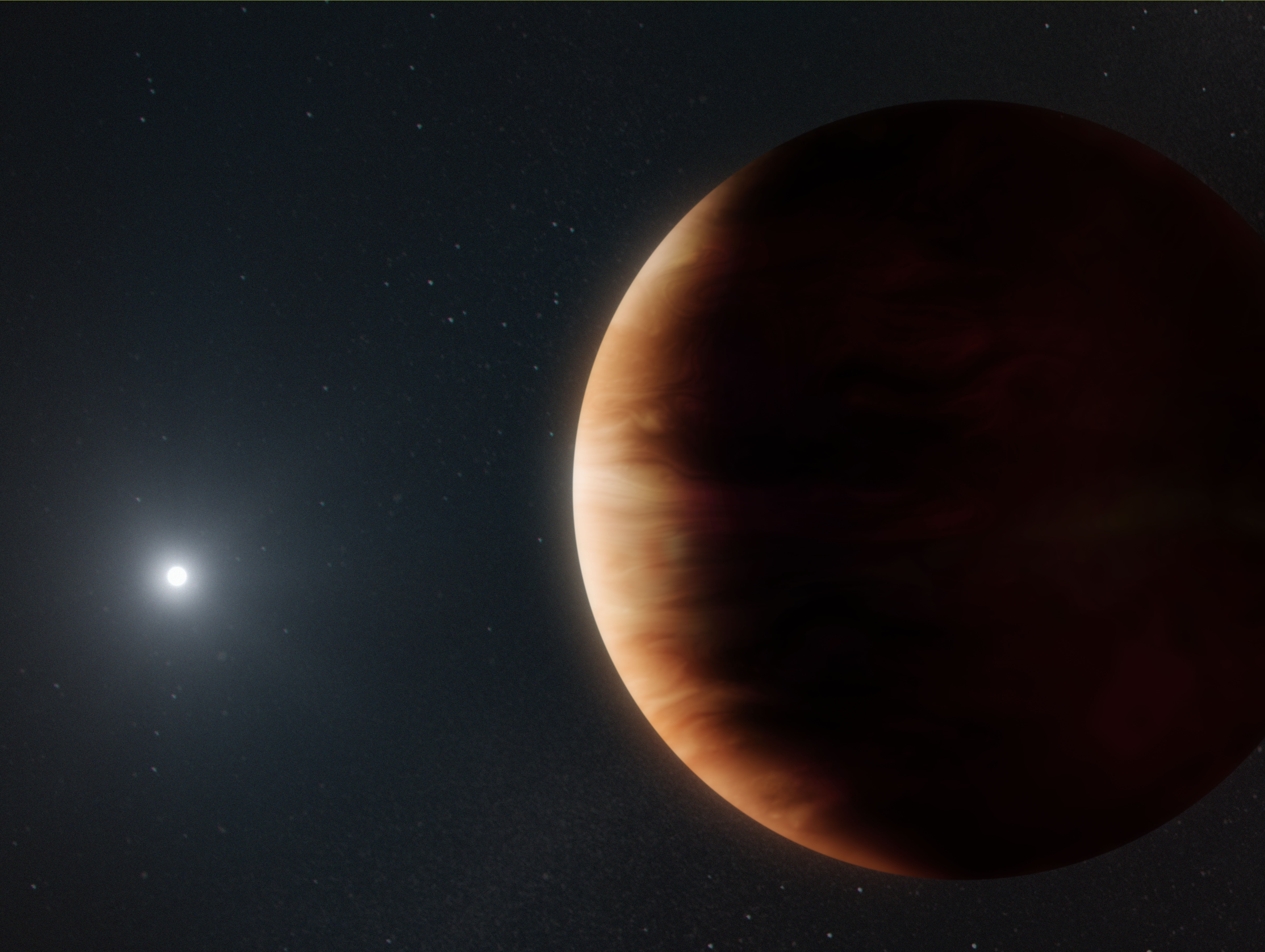

Astronomers have discovered the first confirmed planetary system that offers a glimpse into the fate of our solar system about five billion years into the future. That’s when our sun is expected to exhaust all its nuclear fuel and fade into a white dwarf, or dead star.

The newly discovered planetary system consists of a Jupiter-like planet with a similar orbit revolving around a white dwarf star located near the center of our Milky Way galaxy. This discovery provides evidence that planets orbiting far enough from their sun can continue to exist after their sun dies. The study was published on October 13, 2021, in the journal Nature.

“It is the first known planet orbiting a white dwarf in a Jupiter-like orbit,” said the study’s co-author David Bennett, a University of Maryland astronomer and researcher at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “Earth’s future may not be so rosy because it is much closer to the sun.”

There are a few rare examples of intact planets orbiting white dwarfs in tighter orbits, but these are considered very lucky survivors. Most scientific evidence suggests that planets in closer orbits are consumed or destroyed by the white dwarf they orbit. Simulations predict that larger planets in more distant orbits around stars like our sun can survive their sun’s demise, but until now, there was no evidence.

“Given that this system is an analog to our own solar system, it tells us Jupiter and Saturn could potentially survive the sun’s red giant phase, when it runs out of nuclear fuel and self-destructs,” said Joshua Blackman, an astronomy postdoctoral researcher at the University of Tasmania in Australia and lead author of the study.

When a star like our sun runs out of fuel, all the hydrogen remaining in its core burns off and the sun balloons into a red giant star before collapsing into a white dwarf. At that point, all that is left is a hot, dense core, typically Earth-sized and half as massive as the sun.

Because these compact stellar corpses are small and no longer have the nuclear fuel to radiate brightly, white dwarfs are very faint and difficult to detect. The researchers found the system using the W. M. Keck Observatory on Maunakea in Hawaii.

High-resolution near-infrared images obtained with the Keck Observatory’s laser guide star adaptive optics system paired with its near-infrared camera revealed that the newly discovered white dwarf is about 60% of our sun’s mass and its surviving planet is a gas giant about 40% more massive than Jupiter

The team detected the planet using a technique called gravitational microlensing, which occurs when a star close to Earth momentarily aligns with a more distant star. This creates a phenomenon where gravity from the foreground star acts like a lens and magnifies the light from the background star. If there is a planet orbiting the closer star, it temporarily warps the magnified light as the planet whizzes by.

When the team analyzed the light from the closer star, they found it wasn’t bright enough to be an ordinary star like our sun or even the very faintest star able to burn nuclear fuel called a red dwarf. They also found that the signal wasn’t consistent with a brown dwarf, an object with a mass between that of stars and planets. This led them to conclude at first that the planet must orbiting a black hole, neutron star or a white dwarf. But analysis of the data narrowed their conclusions further.

“We have also been able to rule out the possibility of a neutron star or a black hole host,” said study co-author Jean-Philippe Beaulieu, a professor of astrophysics at the University of Tasmania and Directeur de Recherche CNRS at the Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris. “This means that the planet is orbiting a dead star, a white dwarf.

The research team plans to include their findings in a statistical study to find out how many other white dwarfs have intact, planetary survivors.

NASA’s upcoming mission, the Nancy Grace Roman Telescope (formerly known as WFIRST), will conduct a much more sensitive exoplanet microlensing survey that will further this investigation. Roman will be capable of a much more complete survey of planets orbiting white dwarfs toward the center of the Milky Way. This will allow astronomers to determine how common it is for Jupiter-like planets to survive their star’s final days or if a significant fraction of them are destroyed by the time their host stars become white dwarfs.

###

This story was adapted from text provided by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

Aparna Bhattacharya, an assistant research scientist in astronomy at UMD, also co-authored the study.

The research paper, “A Jovian Analog Orbiting a White Dwarf Star,” was published on October 13, 2021, in journal Nature.